A Meditation on a Poem Out of My Control

(with apologies to Rowan Ricardo Phillips)

Feeling like people could maybe use something to think about that isn’t…well, you know.

—

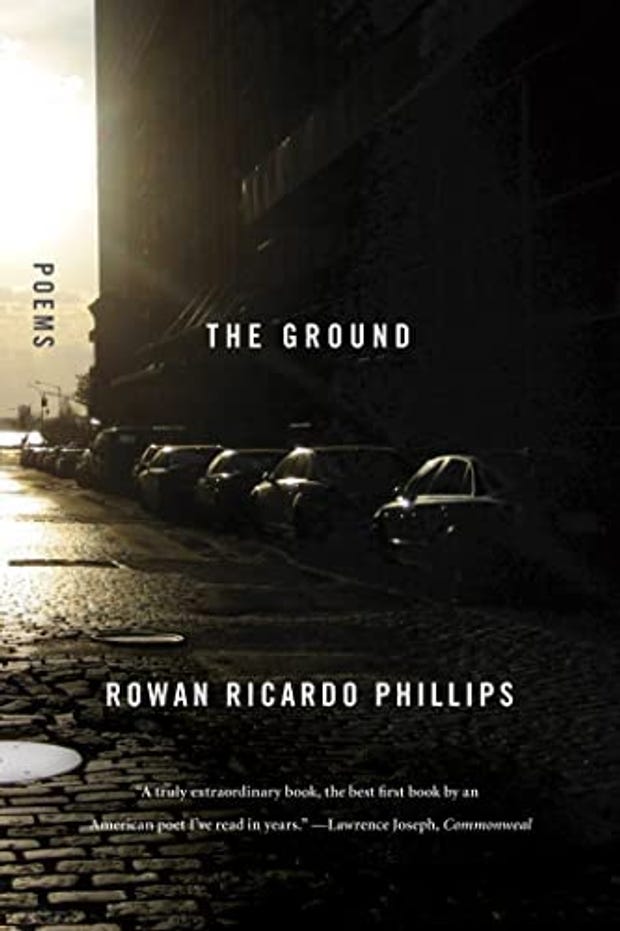

Rowan Ricardo Phillips first book, The Ground, appeared in 2012. It’s pretty great; his poems manage to feel clear and lyrical even while meaning leaches out (or maybe skitters away.) Similarly, his work often centers on a lyrical “I” which is almost the poet himself but then tends to turn into a trope and float out of his life towards some obscure and starry distance.

In poetry in general, and I think in Phillips’ poetry in particular, trying to piece together what’s going on is part of the pleasure, so I thought I’d try to do a close-ish reading of one of my favorites from the book, a mysterious poem called “A Meditation on Many Things Out of My Control.”

A Meditation on Many Things Out of My Control

I grew so tired of doing little, but

I did little more. And from my mores grew

Everything: the horizon, night, a light

Cramped and scattered like blackbirds from a wire

That leave behind nothing, not even the

Wire, not even the six evenings of God

And God’s work, not even the sky-scuffed sea;

Which was north, south, present, past, and future;

Which cracked oil tankers like eggs of speckled

Steel; all just to spite this plain shore who’d said

She was just as beautiful as the moon,

Beautiful as the moon who now smears her.

The first thing out of Phillips’ control here is Phillips himself; the poem begins with him tired of his own lack of doing, which he tries to remedy, but just reproduces, both semi-narratively and linguistically, as the sentence bends back around on itself from “doing little” to “did little more.”

At that point, though, the poem moves from inadequacy to a kind of all-encompassing agency. Phillips says his “mores” (actions? Morals?) grow “everything,” which includes a gesture towards distant space—“horizon, night, a light.”

The contrast between immobilized inadequacy and sweeping reach could be a description of the (or of one) experience of poetry, or of being a poet. Phillips, as a poet, doesn’t control much of anything; he’s just sitting there with the paper (or the computer screen), typing words that can be safely ignored by the horizon. But at the same time, the poet has absolute control (or the illusion of absolute control) over what happens in the poem, which can in fact reach out (as Phillips does) and subsume the night and the distance.

As soon as Phillips’ doing becomes supercharged, though, it deflates, or in this case scatters “like blackbirds from a wire/that leave nothing behind.”

I suspect the blackbirds are a reference to Wallace Stevens’ famous poem “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.” Phillips’ style here isn’t exactly Stevens’, but it nods towards a Wallace-ish play with images as meta-symbols of images. The birds flying from the wire are a poetic image flying from the image, leaving behind “nothing”, or “the nothing that is”, to quote a different Stevens poem. There is no wire—literally; it’s just the word “Wire,” enjambed and isolated at the beginning of a line, floating there in nowhere, birdless and alone.

Nor does the poem contain any part of God’s creation; “not even the six evenings of God/And God’s work, not even the sky-scuffed sea,” Phillips writes. God, like the wire isn’t in the poem. God can create a world and do all the things that Phillips can’t control; the world God made is out there, not in these lines.

Contrasting the poet with God, though, isn’t just a contrast. The poem’s evocation of God’s power and sweep occurs, inevitably, within the poem. Phillips’ rush out to the horizon is reproduced here by God (also Phillips) reaching out in a negation of the “sky-scuffed sea” and “north, south, present, past, and future.”

The rhetorical construction here creates a simultaneous double of assertion/negation. Phillips is describing all the things that are not in the poem (“not even the six evenings of God” “not even the sky-scuffed sea”) even as he puts them (or their images or words) in the poem. God and the sea are out of Phillips’ control, but in saying they are out of his control, he controls them (or their images.) The poem whose title says that it is a humble meditation on what Phillips can’t control is also an assertion of a certain kind of imaginative power linked to repudiation, or assertion of nought.

The next lines revel in the potency (of self, of poetry) or/and despair at the inadequacy (of self, of poetry) by evoking the destructive force of God or the sea, “Which cracked oil tankers like eggs of speckled/Steel.”

As with the enjambment of “wire”, the isolation of “Steel” emphasizes a real solidity disconnected from the real and turned into a symbol. The metal here is not metal, but a word standing in for metal; you can read the passage as a demonstration of how easily the world is shaped by the poet, or of how poetry cracks and sinks in God or nature.

The last lines wash up upon their own double meaning.

Steel; all just to spite this plain shore who’d said

She was just as beautiful as the moon,

Beautiful as the moon who now smears her.

What is the “plain shore” here? It could be the “plain shore” of a world without poetry or human imagination; the reality stripped of poetry. In that case, the final couplet is a repudiation of the idea that the world is beautiful on its own; it must be smeared with the poet’s moonlight.

But it could also be that the “plain shore” is the poem—the words “plain shore” themselves, which are just plain words and not a shore at all. In that case it’s Phillips who is helplessly insisting that his work is “just as beautiful as the moon” rising outside the poem. And it is the moon in the world, and the world itself, that smears him with the knowledge of his own limitations, and of all those things out of his control.

I don’t think it’s one or the other. The repetition of the phrase “beautiful as the moon”—which is quite beautiful in itself—seems like a deliberate reminder that the moon and the moon’s beauty exist here in language; the moon is the moon and it is the word “the moon.” Language is a reflection of the thing, just as the moon’s light is a reflection of sun, or possibly of imagination. The meditation on the many things out of Phillips’ control is also a mediation on the things Phillips does control. A poem touches everything and touches nothing, like those birds lifting off the wire that connects to the nothing off the page, but is still, somehow, there, wherever there might be when you are reading it in a poem.

—

I posted this on my Patreon some years back; I was reading some more of Phillips and was thinking about it again…so here it is.

This is gorgeous: “sky-scuffed sea.” It’s just what I needed today. The reminder that in some ways, we create our own reality. There’s a lot out of my control, but for the most part I choose which words to read and to write. Thank you for helping me remember that.