Are the Supremes a Rock Band?

Genres are often defined by race and gender—and therefore by bigotry.

Note: If you've got Apple Music, you can listen to a playlist of songs/artists mentioned in this post here.

______

This weekend I wrote about Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner’s racist, sexist defense of his racist sexist book, The Masters, in which he interviewed “masters” of rock music—including Bono, Jerry Garcia, Bruce Springsteen, Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan—all white guys.

Wenner didn’t interview Stevie Wonder. He didn’t interview Joni Mitchell. Nor did he interview Diana Ross of the Supremes.

And probably some of you reading this are thinking now something like, “okay…but is Diana Ross rock music? Isn’t she R&B or pop?”

And once you start asking that question, you might extend it to some of those other names too. Stevie Wonder is usually shelved in R&B in record stores, rather than rock. Joni Mitchell might be considered folk. George Clinton is funk—does that count as rock? Maybe Wenner was in part just choosing white guys because rock is mostly a white male genre.

Historically, this argument is pretty weak—as Dee, a critic who used to write at fyeahblackmusic tumblr, explained to me many times over the years. Rock was originally a very integrated genre, with Black and white performers mixing jump blues, boogie woogie, and country into a cool, hot electrified blast of rebellion and sex. Pioneers of the genre included Rosetta Tharpe, Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Little Richard, Etta James, LaVern Baker, Ray Charles, and Clyde McPhatter as well as Bill Haley, Elvis, Rose Maddox, and Buddy Holly. If rock was Black (and female) at its origin, how could we end up thinking of white as a genre for a bunch of white men with guitars?

You’ve probably figured out that the answer is “sexism and racism”, but the mechanics are worth examining in a little more depth. Rock became very popular—it moved from a niche to take over popular music entirely. The most popular performers were those like Elvis and the Beatles, who—by virtue of being white and male—had access to mainstream resources and publicity that were simply unavailable to someone like Rosetta Tharpe or LaVern Baker.

The mainstream, the thing that could really make money for labels and promoters, quickly became, “rock music by white men.” A lot of people then had an interest in labeling and segregating rock music by white men into its own category for easier promotion and so racist listeners (who definitely existed in the 50s and 60s, as they exist now) didn’t accidentally find themselves listening across the color line.

Record labels had long separated race records from hillbilly records for just this reason—even when the music itself was often not so easy to put into such categories (Jimmie Rodgers, the most famous early country artist, played music that probably best characterized as blues, and recorded occasionally with Black artists like Louis Armstrong and Clifford Gibson.)

Applying the same techniques to rock made a lot of sense. So rock performers who were white—like the Beatles or the Stones—were rock. Rock performers who were Black—like Sam Cooke, Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, Sly Stone—were classified as R&B, or funk.

What about rock performers who were Black but insisted on recording in integrated contexts, like Jimi Hendrix? Well, they endured a barrage of racism from white rock critics; Robert Christgau called Hendrix a “psychedelic Uncle Tom,” and used other slurs as well. Hendrix insisted that rock music was his—he wouldn’t stay in the box white people had made for him, and he had to be punished for it. Rock, by the late 60s, was for white people. And especially white men.

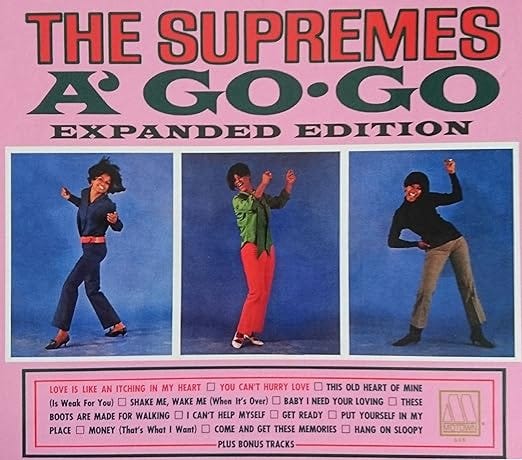

So let’s go back to the Supremes. The Supremes are stylistically quite different from Led Zeppelin, obviously. But…the doo wop vocal harmonies in which the Supremes specialized were central to early rock performers—including The Dominoes’ Sixty Minute Man, sometimes considered the first rock record.

The Beatles were famously fans of girl groups and incorporated the tight harmonies into their own style.

Compare the huge beat of The Supremes’ “You Can’t Hurry Love” to the inert schmaltz of U2’s “With or Without You” —which is more rock?

Or consider Diana Ross’ post-Supremes work with Nile Rodgers of Chic on hits like “Upside Down”. It’s basically New Wave—which used synths, yes, but also harkened back to the less bloated, less guitar-solo driven, more dance beat style of early rock.

Which is why Springsteen, early-rock aficionado, found the New Wave style so congenial himself.

Stylistically, the Supremes and Ross are obviously picking up the same influences and working with the same mix of styles as the Beatles, U2, Springsteen, the Rolling Stones, the Dominos. Diana Ross isn’t excluded from rock because of musical style. She’s excluded because she’s a Black woman, and Black woman are pop or R&B or funk or anything but rock.

Diana Ross is extremely successful; she didn’t need to be “rock” to make money or reach an audience. So you could argue that segregation didn’t really affect her, and that separate, in this case, maybe is at least somewhat equal.

I don’t think that really holds up though. “Rock” isn’t just white and male; it’s also considered more critically important, more central, and generally cooler and more revolutionary than the parallel genres. When Wenner sneers at the intellectual attainments of Stevie Wonder or Janis Joplin, he’s vocalizing the often unsaid critical default. When four white guys pick up guitars, that’s serious, profound and aesthetically rich; when women, or Black people, or especially Black women sing, or play any instrument, it’s just less.

That critical consensus doesn’t necessarily mean that no one buys records by Diana Ross, or Public Enemy, or Beyoncé. But it has influenced who gets covered in magazines, who gets into the Rock Hall of Fame, who gets included on greatest of lists, who is called “Master.” And that in turn can influence whose back catalogue gets a boost, who shows up in history books, who is considered mainstream, who has to put up with racist, sexist condescension from Robert Christgau and Jann Wenner and who does not.

In addition to harming artists—in small ways and sometimes large—the view of our culture as segregated distorts our sense of history and our sense of ourselves. It’s easy for fascist fucks like Trump to offer a vision of a glorious white past when assholes like Wenner have spent their lives insisting that all the culture that matters from the past is white. Republicans can paint multi-racial cosmopolitanism as a new, terrifying innovation when critics have written Black people out of the national soundtrack.

People define themselves by the music they listen to. When that music is segregated by gender and race, people (especially white people, especially men) become comfortable with segregation. Recognizing the Supremes as masters of rock music is a way to remind the Jann Wenner’s of the world that Black women are central to US music and US culture. That’s still a revolutionary message, no matter how white rock critics have tried to dilute it.

You might add a few articulate black men who gave quite articulate interviews on other forums but were never popular with blacks (like Hendrix) and definitely rock. Ben Harper and Lenny Kravitz.

Or you might add one of the most articulate men to ever speak who was never rock but spoke circles around a congressional panel of rather inarticulate white men who blackballed his career for making the look kindegardenish-Mr. Paul Robeson.

For some rather articulate white women who had a clear grasp of the issues of the world you might seek out interviews given by Mary Travers, Buffy Saint-Marie, or Joan Baez (too folk to be articulate enough for Mr. Winner) and sometimes Baez could be full of herself. But how about a German rock legend who never made it in America but was one of the most articulate musicians I ever listened to, Inga Rumpf of one of the best bands in the world when Wenner was beginning his rag, Frumpy.

But I do recall interviews in RS with the likes of Chrissie Hynde and Cherrie Currie that the interviewers were only interested in their sexual proclivities. Look I use to read the magazine for its innumerable reviews but the stories and interviews were never about the intelligence of musicians, but how degraded they could be.Read their interviews with Dylan and compare them to good interviews of Dylan. No contest, the mag was a fanzine at its height that was never very articulate.

I realized that I might be able to better communicate my previous comment with a metaphor.

I was trying to say that it makes sense to celebrate Rock as a big, vibrant, cosmopolitan city and, at the same time, I enjoy the evocative names for the neighborhoods and locations in the city.

I can enjoy wandering around New Wave village, hearing about the parties at Power Pop cul-de-sac, or admiring the Motown hi-rise (and, of course, Blues Highway is the major route to and from.

I can think that it's nice to admire the local character, without trying to argue that any one element should stand in for the whole.