Charles Sumner: Of His Time

Our textbooks don’t want you to know about antiracists in the past.

Were people in the past more benighted, more racist, and less moral than we are? Can you blame people in the 1800s for holding ugly, bigoted views? Or do we have to cut them some slack, and acknowledge that if they were racist, it was because they were of their time? Sure, people in the confederacy kidnapped and tortured and not infrequently raped people enslaved people. But they didn’t know better; if we were around back then, would we have done better?

Obviously no one knows whether they would have behaved well or less well in any particular historical circumstance. But (as I’ve discussed before) the argument that people in the past were worse than people in the present is often predicated on erasing the people in the past who were better—than their peers, and often than us, right now.

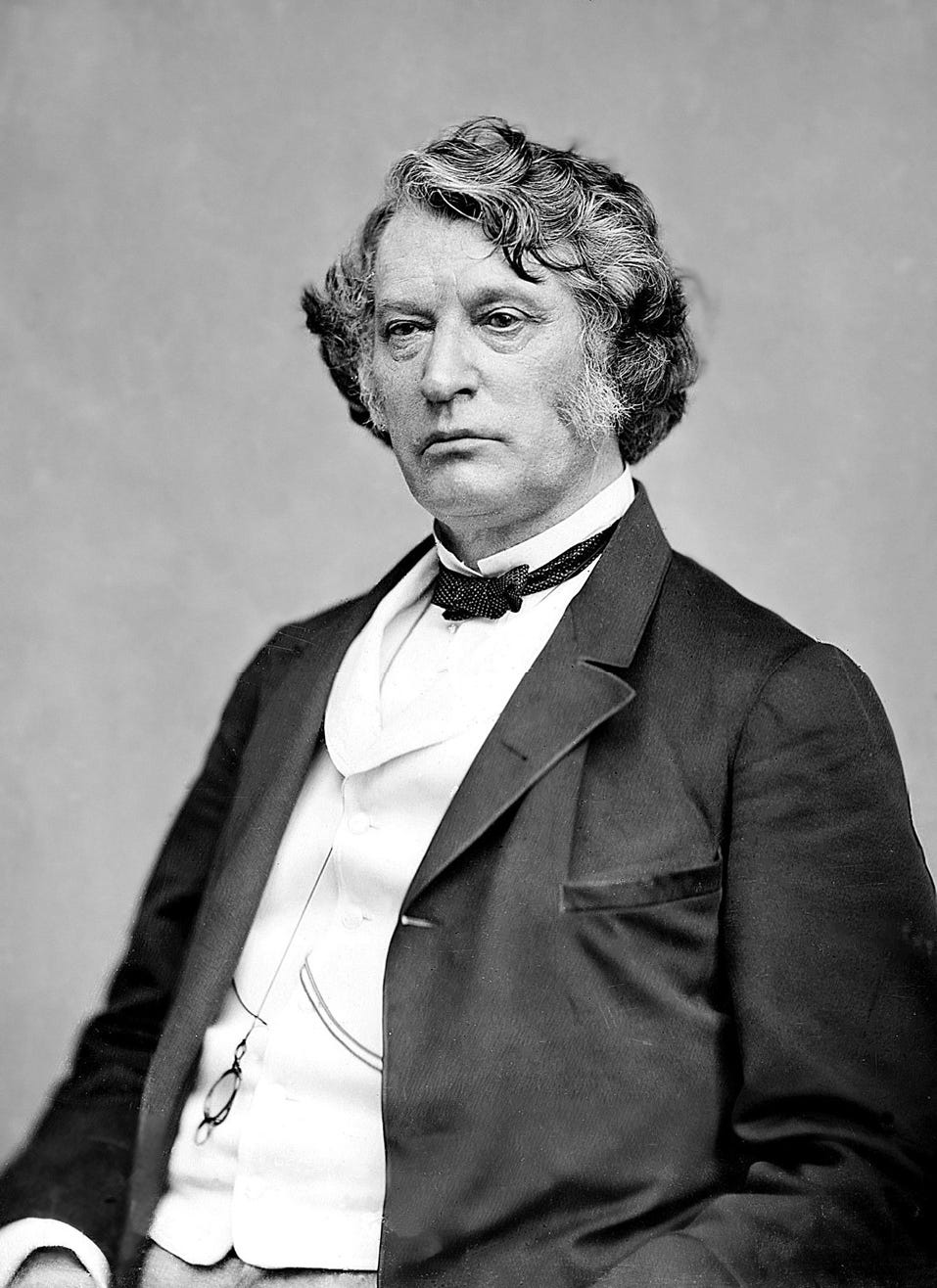

One example is Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner (1811-1874).

—

Everything Is Horrible is entirely supported by subscribers. So, if you like my writing or find it valuable, please consider supporting independent jouranlists and writers (that’s me!) It’s $5/month, $50/year.

—

If you know one thing about Sumner, you probably know that he was brutally beaten on the Senate floor by South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks in 1856. Earlier that year, Sumner delivered a fiery anti-slavery speech in which he personally attacked Brook’s relative, South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler.

The senator from South Carolina has read many books of chivalry, and believes himself a chivalrous knight with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean the harlot, Slavery.

Brooks was so incensed that a few days later he took a cane and beat Sumner almost to death, splitting open his head to the bone. Sumner took almost three years to recover.

The caning is included in most high school history textbooks, at least in passing—it was in The American Pageant, for example, the standard AP History textbook that I used, and that my daughter used some 30 years later. But while textbooks talk at length about Senator John Calhoun’s fight to preserve slavery, and Senator Daniel Webster’s “noble” efforts to compromise with slavery, they don’t tell you much about Sumner except that he said some mean things to slavers and got his head cracked for his trouble.

That’s unfortunate because, as Stephen Puelo makes clear in an excellent recent biography, Sumner was a remarkable man, whose passion for racial justice distinguished him among his contemporaries—and would still distinguish him today.

Equality Before the Law

Sumner’s hatred of slavery, and his disdain for racial hierarchy in all its forms, was the defining commitment of his life. He grew up in a milieu with abolitionist sympathies, but even so, his antiracism was striking.

In 1849, in his first major public address, he argued before the Massachusetts Supreme Court in favor of desegregating Boston’s public schools. Working with African-American attorney Robert Morris, Sumner coined the term “equality before the law,” and—anticipating Brown v Board v. Education a century later—insisted that separate facilities could not be equal, because they established a system of caste. “Caste and equality are contradictory,” he insisted; “Where Caste is, there cannot be Equality. Where Equality is, there cannot be Caste.”

Further, he argued that racism was intended to establish a “nobility of the skin.” Whiteness, Sumner understood, was a class hierarchy—an insight that is still resisted by people on every part of the political spectrum.

Many in the North who opposed slavery (like, say, Abraham Lincoln) were nonetheless racists who did not believe that Black and white people could live together, and who feared that Black people were not fit for democracy or for life in a “civilized” country. Sumner, as his argument in the desegregation case made clear, was opposed not just to slavery, but to segregation and all other manifestations of racism.

He demonstrated this over and over, and over and over he took stands that put him at the forefront of antiracist thought for his own day, and in many ways still for our own. In the debate about the thirteenth amendment, he attempted to remove the clause that allowed slavery as punishment for a crime, because he believed that slavery was contrary to the constitution and to God, and should never be allowed in any circumstances.

Similarly, during the debate on the fifteenth amendment, he tried to get language included which would not only enfranchise Black men, but which would guarantee Black people the right to hold all national and local offices. He also wanted to specifically prohibit literacy, property, or education tests for voting—tests which were common, for various reasons, in the north as well as the south.

Sumner’s last words were “Don’t let the civil rights bill fail.” He was referring to legislation he had drafted and pushed which, according to his biographer Puelo, “would have prevented any form of discrimination based on color anywhere in the country by theaters, inns, ‘common carriers’ of passengers, managers of schools, or any church, cemetery, or state or federal court—including restrictions on juror service.”

Most of these policies went down to defeat in Congress. You could say that Sumner was ahead of his time. But you’d have to say he was ahead of our time, then, too, because many of these provisions would also be opposed by MAGA. It’s impossible to imagine Donald Trump’s Republican party agreeing to add explicit voting rights protections to the Constitution. It’s difficult to imagine that they would agree to Sumner’s civil rights bill either, which they would no doubt view as an example of that hated “DEI.”

Sumner, Not Enough Of His Time

Sumner was not a paragon or a saint. He was unbending and clear-eyed in his hatred of racism, but in other areas he could be—well, less clear-eyed. Like many male abolitionists, he did not have the same passion for women’s rights as for Black rights, and he infuriated feminist abolitionists by refusing to fight to enfranchise women (white or Black) at the same time as freedmen were enfranchised. His famous oration against Butler was filled with mockery of the senator’s disability; he had just suffered a stroke and Sumner sneered at his difficulty in speaking.

Like everyone, Sumner had blind spots. But his admirable, thoughtful, determined antiracism shows why you can’t just attribute those blind spots to the year in which he happened to be born. Because, when it came to antiracism, Sumner was not just more progressive than most people of his day, but more progressive than most people of our day. His clear-eyed demand for equality before the law, his excoriation of compromise with hate and his loathing of the compromisers, would make him a very welcome addition to the Senate today.

Sumner speaks not just to his time but to our own. And that’s precisely why he—and those like him—are so enthusiastically and efficiently erased from the textbooks and from historical memory. When people say that racism in the past was “of its time,” what they really mean is that racism just needs to be accepted, like rain or insect bites. It’s part of the environment—a natural, understandable phenomena, which you can’t really do anything about. People were just racist then; they’re just racist now; what can you do? Just wait for it to pass—or not pass, as the case may be.

But Sumner refutes that. He lived in a day when racism was much more overt (or was it?) and much more accepted (or was it?) And yet, he figured out that racism was wrong, and devoted his life to fighting, not just slavery, but the entire idea of caste and inequality. And if he did that then, why can’t we do the same now?

That’s a question that, it’s clear, many politicians, and many textbook writers, don’t want to ask themselves, and don’t want you to ask yourself. They don’t want Americans to have antiracist heroes; they don’t want Americans to know that their political leaders can in fact take a stand against evil. The past is not even past, as someone said. The time in which we take a stand, or don’t, is always now.

It’s wilful ignorance to think that people who lived before were different in any way from us. As if racial or gender equality were novel concepts.

Everyone who’s experienced adolescence knows that their beliefs are a choice: they can choose or not to accept what they’ve been taught at school or home (or online…). A six yo can’t be blamed for parroting a parent but a 26 yo must own their beliefs. A person’s ethics are immaterial to what the majority thinks at the time.

I study historical feminist women writers and some had male allies (which is how many of them managed to have their works survive), more than I originally expected. It’s always possible to do the right thing. And it’s always wrong to harm others. Acknowledging those wrongs is a commitment to be better; giving them a pass continues the wrong.

Thank you for this.