Emily Dickinson Demands That God Pay Up

On "I never lost as much but twice"

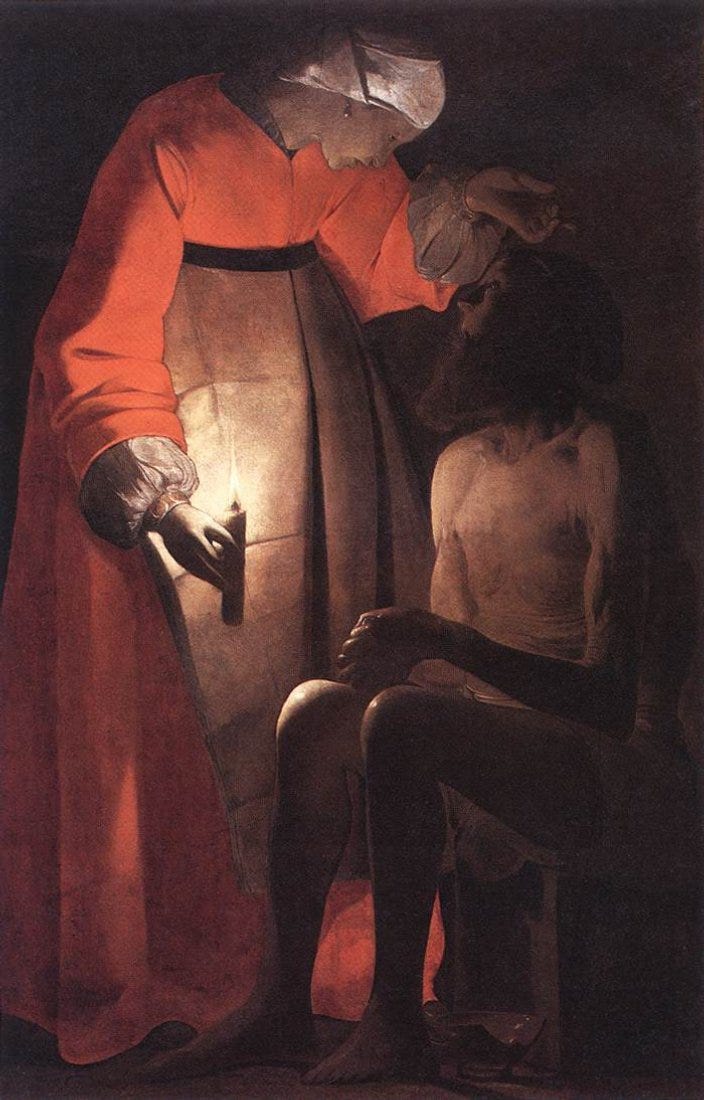

Gustave Doré, “Job and His Friends”

I never lost as much but twice—

And that was in the sod

Twice have I stood a beggar

Before the door of God!

Angels—Twice descending

Reimbursed my store—

Burglar! Banker—Father!

I am poor once more!

I first read Dickinson’s “I never lost as much but twice” when I was in high school. It stuck in my head, partly because of its mystery. Who is she mourning? Who fell into those dramatic slashes and spaces in the text, never to be seen again? My teacher didn’t do a great job of explicating or answering my questions, but I figured I had time. Someone at some point would tell me what this poem was about.

Thirty-five years later, I still have the poem memorized, but I can’t exactly say it’s become clearer. The “I” and the reference to three tragedies makes you almost demand a biographical reading. But if Dickinson was referencing a specific incident or incidents, scholars have had limited luck pinning down the details.

Who’s in the sod, anyway?

The ms dates to 1858, when Dickinson was 28. That makes it one of her earlier works (the collected edition I have, arranged in loose chronological order, numbers it 49 of some 1775 poems.)

By that age, Dickinson had suffered a lot of loss. When she refers to losing two close friends (or more than friends?) to death (“in the sod”), she might be talking about:

— Sophia Holland, a second cousin and close friend, who died in 1844 when Dickinson was 14

—Leonard Humphrey, the principal of Amherst Academy where Dickinson studied; he died suddenly at age 25 in 1850 when Dickinson was 20

—Benjamin Newton, Dickinson’s father’s law student who became a close family friend and mentor; he died in 1853 when he was 32 and Dickinson was 23.

It’s possible Dickinson wrote the poem in 1853, or that she is remembering the experiences of 1853, and is memorializing the loss of Newton while thinking about Humphrey and Holland. Or she might be talking about Humphrey and Newton as the two people she lost “in the sod,” and writing about a new tragedy—one that may or may not involve death.

That third tragedy is trickier to identify, though. Susan Gilbert, Dickinson’s close friend and possibly a romantic interest, married Dickinson’s brother Austin in 1856. There’s not much evidence that Dickinson saw that as a blow, but losing one’s love to a sibling certainly seems like it could be traumatic. Dickinson’s mother also became very ill in the mid-1850s; Dickinson spent much of the rest of her life caring for her. Maybe Dickinson experienced her mother’s illness as a loss.

Or it’s possible that Dickinson had a different romantic or personal relationship which was cut off that we don’t know about. There are a series of letters to an unknown “Master” starting in 1858. She probably isn’t referring to him (whoever he was) in this poem, but it’s a reminder that there are significant parts of Dickinson’s private life we don’t know much, or anything, about.

Ivan Meštrović, “Job”

Three Lost, Three Beat

There, somewhat unsatsfyingly, endeth the biographical reading. But the mysteries arguably give the poem additional power. As with much of Dickinson’s writing, “I never lost as much but twice” has a feeling of great compression, as if it’s about to explode out of its syntax. Meaning has been pounded down into an essence that’s so brilliantly clear it becomes difficult to parse.

In “I never lost,” the sense of an eruption barely held back is emphasized by the scansion. The first quatrain is iambic; the syllables are unstressed/stressed. Iambs mimic the flow of natural speech in English, and the first line, with four beats (iambic tetrameter) is almost reflective; you feel like you’re at the start of a typical Victorian/romantic lyric, which will offer up songbirds or daffodils or some such.

I never lost as much but twice—

And that was in the sod

Twice have I stood a beggar

Before the door of God!

The next three lines in the quatrain, though, accelerate. They’re in iambic trimeter—six syllables, unstressed, stressed, meaning that each line has three beats. The rhythm is uneven, tightly wound, and drastically cut off in comparison to the usual Shakespearean pentameter (which Dickinson was very familiar with). The poem accelerates, like a shovel banging more insistently on a coffin lid. The last line, with the exclamation point, sounds like it’s wailed from outside the gate, “Before the door of God!”

Angels—Twice descending

Reimbursed my store—

Burglar! Banker—Father!

I am poor once more!

The next quatrain switchs from iambs to trochees; stressed/unstressed. It sounds like she’s shouting, or like her emotion has overwhelmed the craft, and she can’t get the words out quickly enough.

That’s especially the case in that indelible third line. Some versions of the poem I’ve seen (including in my collected edition) try to smooth out her punctuation, rendering the line as “burglar, banker, father.” But that loses the lines sharp, cutting edges, and the way the stressed syllables (Burg/Bank/Fath) pound like fists on that closed door. The final line is still three stressed syllables, but it drops the final unstressed beat. That’s why the five syllable “I am poor once more!” has such a foreshortened finality. There’s supposed to be more after that “more,” but instead there’s only the exclamation point of silence, a last beat cut off.

Léon Bonnat, “Job”

Job and the Banker

Dickinson’s main influence as a poet was the Bible, and “I never lost as much” is often read as a critique of Puritan reverence in general. But I think it can also be seen as a direct response to the story of Job, and to one of that story’s most disturbing aspects—its framing of present fortune as making up for past grief.

In Job, the Devil bets that he can make a righteous man curse the name of God. God agrees to the trial, and so the Devil takes Job’s wealth, his health, and his children. Job remains steadfast in his faith, though, and God eventually restores him.

The Lord blessed the latter part of Job’s life more than the former part. He had fourteen thousand sheep, six thousand camels, a thousand yoke of oxen and a thousand donkeys. And he also had seven sons and three daughters.

Which sounds lovely, but…children aren’t sheep or camels. Their value isn’t measured by how many of them you have. God gave Job seven sons and three daughters, but those aren’t the children he had before, who are now in the sod, and unrecoverable. A God who treats children as interchangeable, or human beings as a mere source of wealth for their parents, is a monster, not a comforter.

Dickinson’s poem is a kind of parody of the logic of Job. She too, in the poem, treats loved ones as interchangeable, nameless numbers. Each loss is not an individual tragedy, but a counting exercise. “I never lost as much but twice—/and that was in the sod” is ambiguous because it’s not clear whether the third loss is a death or not. But perhaps that’s the point; the narrator can’t distinguish between death and simply losing touch, just as God in Job seems not to understand the finality of what he’s done when he murders Job’s children, or allows them to be murdered.

Angels—Twice descending

Reimbursed my store—

Burglar! Banker—Father!

I am poor once more!

The second stanza is even more explicit about the monetization, or capitalization, of grief and love in Job, or in patriarchy. The angels descend like mercantile middlemen, bearing love as reimbursement, filling up the store just as God gave Job some camels and some daughters.

But if prosperity gospel beneficence is handing you a new child like a new yacht, then hardship is an exercise in miserly mean-spiritedness. God is a “Burglar!” and a “Banker—Father!”—a divinity of rapacious, greedy spite, who profits from the misery of his grieving subjects/debtors. And that misery is repeated and reiterated until it is final. Job has, and loses, and then has again. But in Dickinson the loss bangs on through three beats, and more. Job’s second set of children will also die, or Job himself will die; grief cannot be answered with a further loan, because that loan also inevitably comes due. The burglar who steals and the banker who repossesses always have the last word—or the last emptiness after the “more.”

William Blake, “The Examination of Job”

Take That, Nietzsche

If the poem is about disillusionment with God, then one possible reading is that it’s about…disillusionment with God. Or to put it another way, the third death that God can’t repair may be the death of God himself.

There’s some biographical evidence here. Dickinson experienced a religious revival in 1845, the year after her cousin died. “I never enjoyed such perfect peace and happiness as the short time in which I felt I had found my Savior,” she later wrote. But the conviction of salvation didn’t last. Her later religious commitments are unclear; friends and relations insisted she was a believer, but the poems are ambivalent. In any case, she certainly had an experience of finding God and losing him—a different loss than death.

The hyphen at the end of “Reimbursed my store—” is a beat or space in which the narrator experiences a third loss; the stores are depleted again. It can also though be a turning point in which the narrator realizes that a God who sees love as chattel is going to take everything in the end. And that “Burglar! Banker—Father!”—isn’t a father she wants to know or worship.

What is lost in the poem may be love. But it could also be faith. Before the door of God, the beggar receives dashes—spaces that mark time until eventual blankness. A God who takes away isn’t really God, which means that poverty is an eternal state. It returns for Job, and again for everyone.

How freaking splendid is this essay.

Great piece Noah! And about my first favorite poet too! Yay! (The other favorite is Coleridge, possibly because I am a Philistine. 🤣) The first time I ever read her (12? 13?) I was like, "Now THIS is the good shit right here."

elm

i could totally see the lady snarking at god