Every David Lynch Movie, Ranked

David Lynch (1946-2025)

In the middle of everything else, David Lynch died this week. I wrote up this ranking of all his films, which I don’t think is available online anywhere. So I thought I’d re-up it as a tribute of sorts.

—

David Lynch’s movies are obsessed with the persistence and failure of identity, so it’s not surprising that his ten films are both like and unlike themselves. His movies circle around the same actors (Kyle MacLachlan, Laura Dern, Harry Dean), the same genres (noir, melodrama), and the same themes (disability, sexual violence, infidelity, the movies), and distinctively surreal, or hyer-real, absurdist visuals. But over his career he’s also continually tried to get out of the limitations of his own style, shifting from semi-narrativeless experiments to genre, to big budget FX blockbusters to wholesome kid’s movies, and ultimately moving away from film altogether for the smaller box of television.

Ranking Lynch’s films is tricky both because they’re so similar—they almost seem to comprise a single work—and because how do you rank the space opera vs. the 19th century biography vs. the three-hour jumble of tropes?

Be that as it may, we’re here to bring a cool Lynchian formal order to the improvisatory Lynchian mess, and that’s what we’re going to do. Every Lynch film at least looks lovely, and he generally includes something of interest in even his worst efforts. But inevitably, some of his efforts have been more best than others. Here then is the definitive list of all ten Lynch movies, ranked from “don’t you look at me!” on up to “damn fine coffee.”

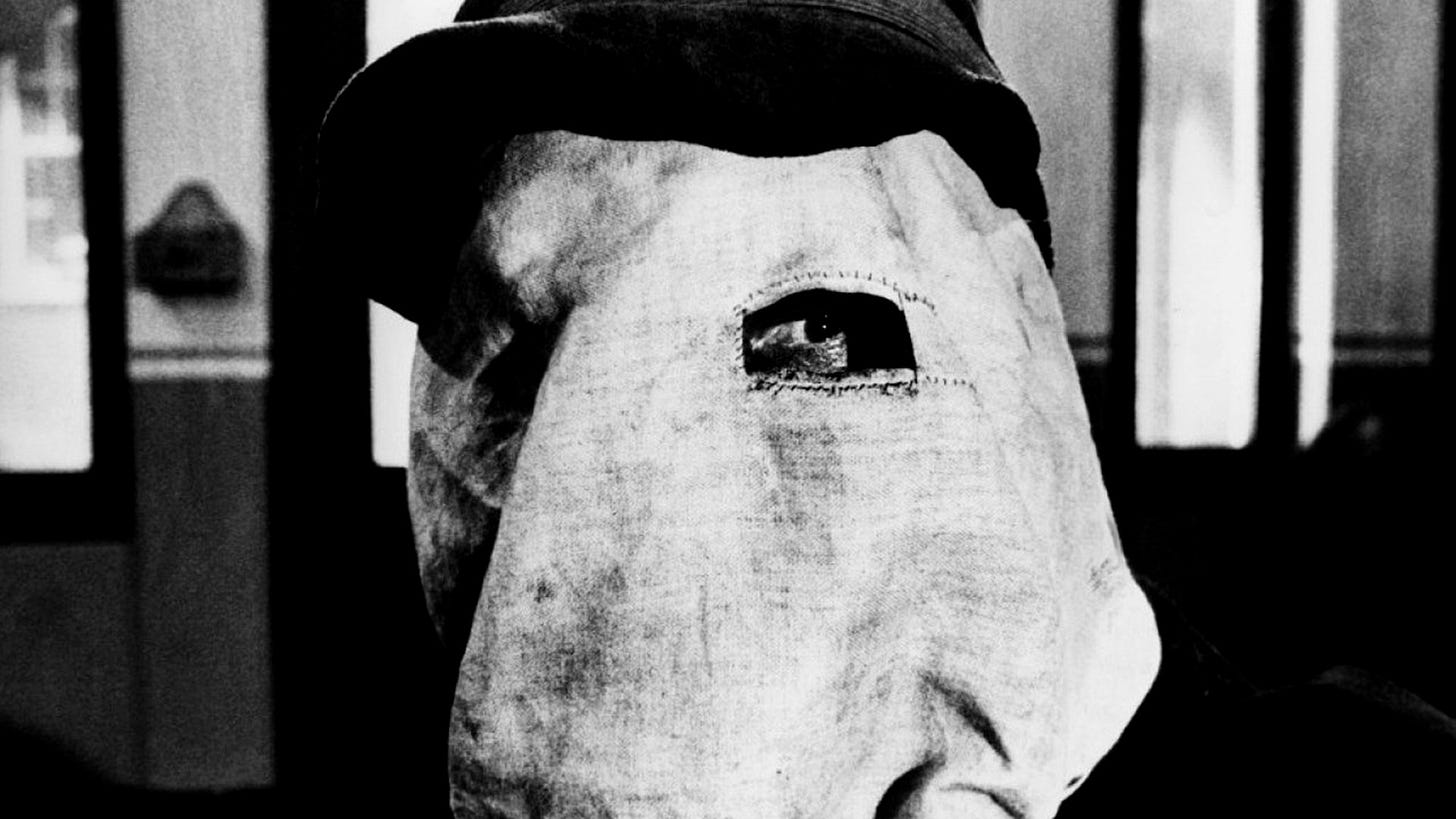

10. The Elephant Man (1980)

As a filmmaker, Lynch is most interested in exploring dream states and the places where genre tropes crumble into the subconscious. A somber biographical film seems completely ill-suited to his talents—and sure enough, his second movie, “The Elephant Man,” is an aesthetic and ethical mess.

The movie supposedly tells the story of John Merrick (1862-1890), a London man who suffered from extreme deformities, probably as a result of Proteus Syndrome. In fact, though, Lynch is much less interested in Merrick’s life than in the horror, pity, and sympathy he inspired in others. The movie resolutely refuses to explore Merrick’s perspective; instead, it keeps putting him on display for others. In an unforgivable choice, Lynch keeps Merrick (John Hurt) hidden from viewers for a long stretch at the beginning of the movie; when we finally see him, it’s through the eyes of a maid who shrieks and runs screaming.

The film delights in heaping indignities on Merrick; it makes up a whole episode in which he is captured from the hospital where he spent the last part of his life and returned to a circus freak show, just so it can have further scenes of him being beaten and humiliated. His doctor, Frederick Treves (Anthony Hopkins) occasionally worries about whether he is exploiting Merrick, but this just adds depth and resonance to Treves; the film itself doesn’t make much effort to address the problem of representation it raises with any seriousness.

Merrick, for his part, is rarely allowed to express bitterness or anger, or to demand equal treatment; the one exception is a mob scene that is lifted fairly obviously from “The Merchant of Venice” by way of James Whale’s “Frankenstein.” “I am not an animal!” Merrick shouts, and Lynch seems to think we should be impressed by this elementary observation. The lethargic plot wanders between voyeuristic disgust and smug satisfaction at the film’s broad-mindedness. Lynch never made another film as tedious and tone-deaf.

9. Lost Highway (1997)

“Lost Highway” has one of Lynch’s cleverest narrative structures. The protagonist, saxophonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) murders his wife Renee (Patricia Arquette), is convicted, and then in his jail cell changes into a different person—auto mechanic Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty). The plot loops around, as mysteries from Fred’s life rhyme with mysteries in Pete’s, because Pete seems to be Fred’s lost past, or vice versa.

Unfortunately, that all sounds like it would be more fun to watch than it is. The movie snags ideas from earlier film projects and reworks them in less insightful ways. It uses noir tropes without the flamboyant exuberance of Blue Velvet; elaborates a lover’s heist without making you care about the lovers as you do in Wild At Heart; uses a split personality abuser without the sympathy for his victims that makes Fire Walk With Me so painful and terrifying.

Swapping people’s identities around makes it difficult to make them distinctive or interesting, and Lynch refuses to commit to any clear theme beyond the standard misogynist noir trope that women who have sexual autonomy are evil and maybe deserve to be murdered. He attempts to hold your interest with a lot of topless scenes and some dramatic violence, but unfortunately, since most of us can’t change into someone else halfway through the runtime, the movie still ends up being a slog.

8. Inland Empire (2006)

David Lynch's final film is a bold departure. It is entirely composed of scenes of Laura Dern starting to say something, and then changing her mind, interspersed with lights flickering. It is 150 hours long.

Okay, okay, it's not quite that long, but it can feel like it. The real runtime of "Inland Empire" is "only" 180 minutes, and there is a vague plot of sorts. Dern plays Nikki Grace, an actor appearing in a (possibly) cursed experimental film about an adulterous love affair. Meanwhile, Nikki herself carries on an adulterous love affair with her co-star. Nikki maybe thinks she's becoming her character, and maybe is becoming her character. Also she's haunted by ominous Polish people and sex workers, the latter of whom occasionally perform girl-group dances to songs like "The Loco-Motion." To add to the confusion, Lynch includes scenes of a sitcom featuring an anthropomorphic rabbit-headed family and a loud laugh track.

There are fans who swear by "Inland Empire," and then there are fans who swear at it. The movie has some undeniably fun bits. Lynch shot it on hand-held digital video, and its grimy look is engagingly unusual. He uses clever cuts so you're not sure if you're watching the film or the film within the film. Dern's extended monologue about gouging a rapist's eye out is compelling, as is the visual image of her face twisted into a bizarre laughing mask. But, for me at least, the movie's studied, deliberate refusal to develop interesting characters, provide a plot, or to say anything gets old after three hours.

—

This is where I’d paywall this if I were going to. I’d rather not though. So…if you find my writing valuable, consider becoming a paid subscriber so I can keep on with work like this. It’s $50/year, $5/month.

—

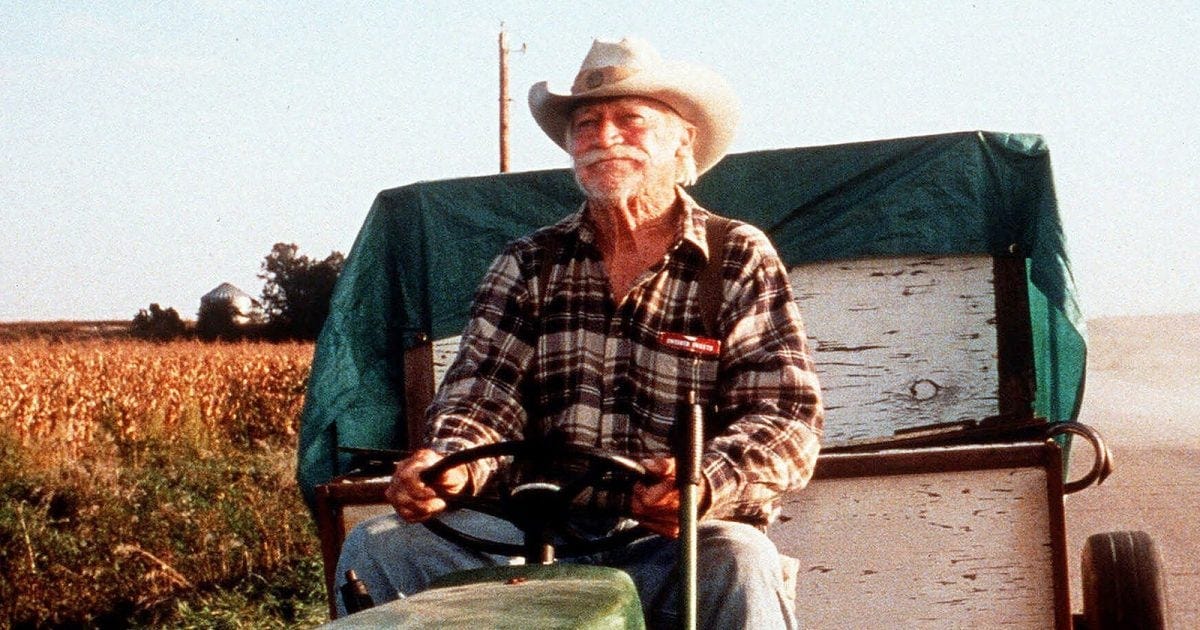

7. The Straight Story (1999)

A G-rated David Lynch picture released by Disney sounds like a dubious proposition, but "The Straight Story" works surprisingly well. Alvin Straight (Richard Farnsworth), 73, with poor eyesight and a bum hip, learns that his estranged brother has had a stroke. So, he buys a John Deere mower and travels from Iowa to Wisconsin to see him, having some heart-warming encounters along the way.

If you're a sucker for sentimental Americana, this is of significantly higher quality than the genre usually manages. Lynch's panoramic views of the Midwest are lovely, the soundtrack is Angelo Badalamenti's most meltingly romantic, and Farnsworth, who was ill with cancer at the time, turns in a wonderfully low-key performance.

On the other hand, if sentiment makes you itch, at least "The Straight Story" contains some interesting insights for Lynch fans. After seeing it, for example, it's clear that the over-the-top portrayal of small-town life in "Blue Velvet" isn't meant entirely derisively. The way that "The Straight Story" treats aging suggests that Lynch has grown since making films like "Eraserhead" and "Elephant Man," in which disability is shown from the abled's perspective and treated like an object of horror and pity. You could argue that the "The Straight Story" is inspiration porn, but at least its story is told through Alvin's eyes. He gets to be the hero of his own narrative. The movie is slight, but it's hard not to applaud Lynch for trying something so different.

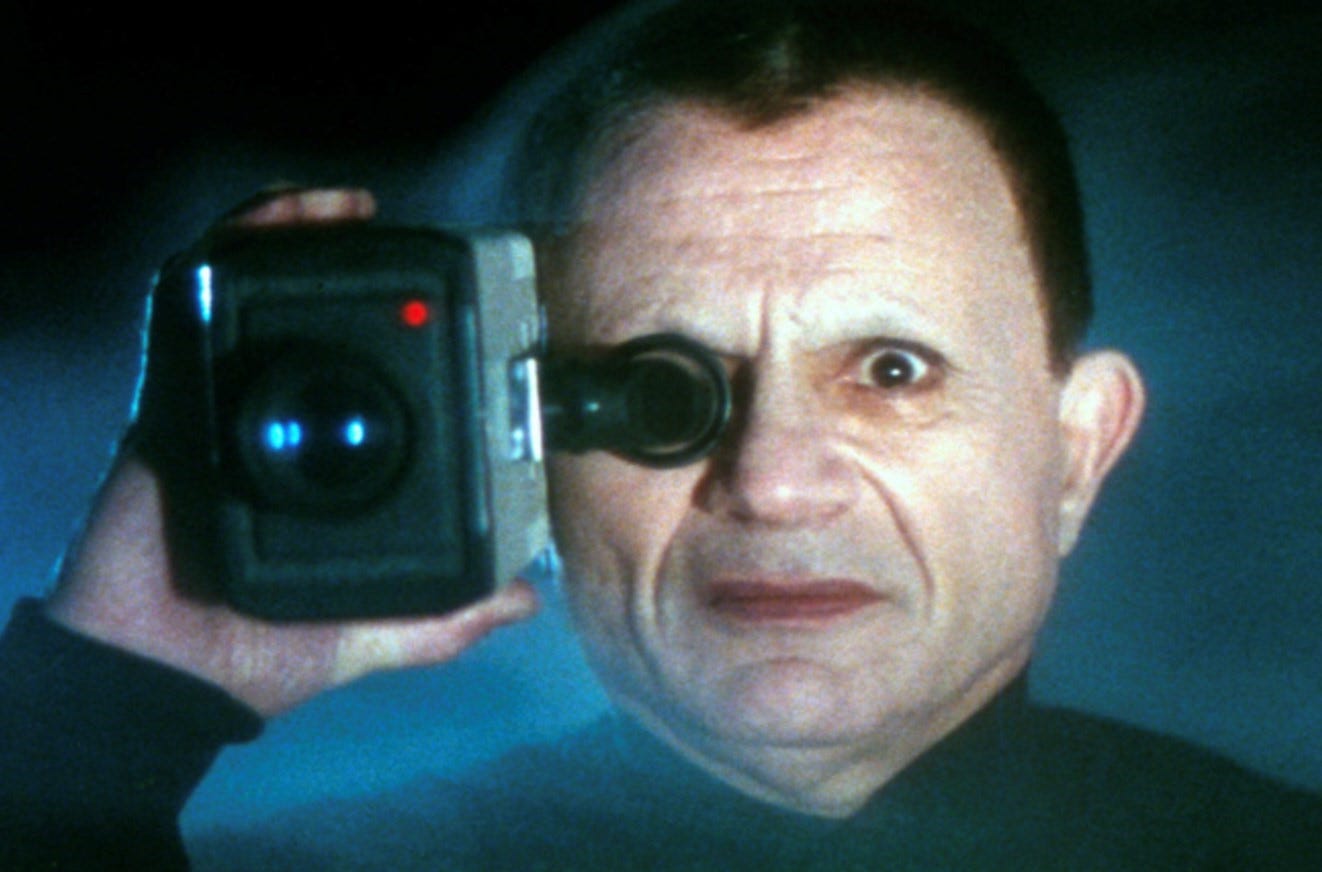

6. Dune (1984)

“What if Star Wars, but with every iota of fun surgically borified?” That is probably not exactly the question Universal Pictures was asking, but it is the call that David Lynch answered. Dropped into the great desert of Hollywood blockbuster with only Frank Herbert’s bloated, pompous, hippie novel as a guide, Lynch went about creating a world even more bloated, even more pompous, and even more drug-addled. The cast led by Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides/Maud’Dib/Usul/etc. intones sententious quasi New Age burble (“Fear is the mind killer!” “They tried and died!”) with an affect as flat as the gorgeously chintzy matte paintings, while great worms of exposition rise to bellow hollowly and sink once more beneath the towering drifts of plot.

It would be a stretch to call this movie good, or even adequate, but it has an undeniable Plan 9 From Outer Space appeal, with severed pulp tropes wandering about blankly, bumping into blue contact lenses here and stumbling over odd stunt casting there (Patrick Stewart? Sting?!) This is art-director genius Lynch’s one true venture into utter trash, and if you can get through it without giggling in delight a time or three, then you may be the Kwisatz Haderach himself. Or maybe you’re just taking the wrong drugs, who knows?

5. Eraserhead (1977)

David Lynch’s stunning debut remains a weird touchstone for art cinema snobs and lovers of the surreal everywhere. The soundtrack alone is a work of genius—all echoing industrial hiss and haunting ambient clatter. Similarly, many of the black and white visuals—like Henry (Jack Nance) framed in a halo of his own hair, or Henry cutting into a miniature chicken which thrusts its legs sexually and oozes blood—have become icons of goofy oddball dread.

The loose narrative is also contradictorily perhaps Lynch’s most thematically focused. Henry seeks love and finds instead gross bodies, sexual repulsion, and an ugly twisted child-thing which whines and mewls and demands care. It’s a coming of age movie for repressed sexual dysfunctionaries.

Lynch’s daughter Jennifer was born with two club feet, and the film reads as an autobiographical nightmare about his insecurity about fatherhood and his fascination with and loathing of disability and broken or diseased bodies. Eraserhead can drag a bit, and as a parent I have to admit that his metastasizing self-pity in the face of a child’s suffering is kind of irritating. But, even despite some wonderful homages like Tetsuo: The Iron Man, there’s nothing else in cinema quite like it. Of all David Lynch movies, this is the David Lynchiest.

4. Mulholland Drive (2001)

“Mulholland Drive” was originally supposed to be a television pilot, and it has an unfinished feeling; several scenes (a hysterical botched hit, an unnamed character encountering a nightmare man from his dreams in a diner) seem like they’re randomly pasted in from a larger work.

This isn’t exactly a weakness though; the movie is about Hollywood and the process of assembling movies out of money, more or less fortunate actors, dreams, and the spackle of happenstance. A young actress named Betty (Naomi Watts) meets an amnesiac named Rita (Laura Elena Harring), and the two try to piece together her story—creating their own movie, as it were, until they fall in love, and then, as movie project sometimes do in Hollywood, the whole thing unravels.

One common interpretation of the movie is that it’s the hallucination of failed actress Diane (also Naomi Watts); sort of “Sunset Boulevard” meets…well, David Lynch. You could also see it, though, simply as Lynch cheekily demonstrating that movies still hold your attention even when you know they’re fake, the way that the audience still hears the trumpet in club Silencio even when the player walks offstage.

To demonstrate the magic of cinema, Lynch employs numerous tricks—narrative fissures, two actors playing the same character, one actor playing two characters. His main weapon, though, is Naomi Watts, who plays innocent eager hick striver, bitter desperate jealous murderer, new love, old love, and virtuoso scenes within scenes in an absolutely dazzling bravura turn. She steals the show in part by showing it’s all a show, which makes it perhaps the Lynchiest performance in his entire oeuvre.

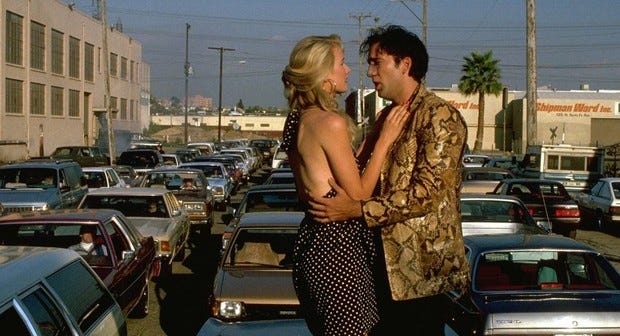

3. Wild At Heart (1990)

Roger Ebert wrote a scathing pan of “Wild At Heart” when it was released. He despised the opening scene, in which Sailor (Nicolas Cage) murders a Black killer hired by his girlfriend’s mother Marietta Fortune (Diane Ladd). The film, Ebert argues, tries to excuse its violence and cruelty as “parody;” it is “a film without the courage to declare its own darkest fantasies.”

Lynch’s attitude towards his material is always a little difficult to parse, and there are certainly elements of mockery in his depiction of lovers Sailor and Lula (Laura Dern.) But for me, at least for the most part, Lynch’s belief in them is as sincere as anything in his work; he loves the couple, and wants you to love them too. Yes, Sailor’s Elvis accent and snakeskin jacket (his "personal symbol of individuality") are silly, and Lula’s enthusiastic ode to his penis and how it talks to her while it’s inside is both saccharine and gross.

But love is silly, saccharine, gross and wonderful all at once, and Cage and Dern make it unequivocally clear that they care for each other, whether they’re stopping the car to kung-fu dance to speed metal or having hard conversations about past betrayal or trauma. They overcome mother’s (hyperbolic) opposition, their own (incredibly) poor choices, violence, and prison, and unless your heart is a big old lump of rock (or you’re Roger Ebert, I suppose), you’ve got to swoon at least a little when Sailor serenades her with “Love Me Tender” at the close. Stylized absurdist cold-hearted weirdo Lynch manages to succeed where romcoms often fail—he gives you a unique couple who both obviously care for each other, and who you can imagine being happy together.

2. Blue Velvet (1986)

Lynch’s first noir is also, inevitably, his first meta-noir. The movie functions as a somewhat straightforward genre exercise, with the morally ambivalent hero Jeffrey (Kyle MacLachlan) torn between good wholesome girl Sandy (Laura Dern) and the dark BDSM charms of seedy nightclub singer and femme fatale Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini). But it’s also a mash-up, inspired as much by Douglas Sirk as Jim Thompson, in which the manicured lawns of Reagan’s wholesome suburbia peel back to reveal insects chewing on ears in the grass—or alternately, in which the corrupt face of evil cracks open bloodily to reveal an even more disturbing sunlit smiling façade inside.

The most famous scene is ostentatiously about the gaze, in which the viewer is positioned with Jeffrey watching a primal scene through the slats in a closet. That scene is one of Lynch’s most infamous: manic thug Frank (Dennis Hopper) breathes through some sort of gas mask while spewing profanity, chewing up all the scenery, and raping the masochistic Dorothy, who appears to be aroused despite herself.

Jeffrey, like Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window before him, wants to watch the performance of violent, depraved sexual violence. But he also wants to watch the corny 50s sitcom where high-schoolers talk about robins and love and the town motto is “Lumberton; the town where people really know how much wood a woodchuck chucks!”

Jeffrey’s aunt watches a robin feeding at the very end of the film and exclaims, “I don’t see how they could do that. I could never eat a bug.” But the horror, or the joke, of the film is that Jeffrey, and the viewer, and Lynch himself, all like eating bugs—and all like to recoil from robins eating bugs as well. Lynch would explore this terrain further in Twin Peaks, but Blue Velvet is where he perfected the view.

1. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992)

The first half hour or so of this 135 minute film involves quirky FBI agents tussling with local law enforcement and using tailoring as secret code; it’s as if Lynch wanted to lull fans of the TV series into a false sense of being on familiar ground. After that, though, the movie shifts to the last days in the life of Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee), and becomes an unrelentingly scalding portrait of sexual assault and incest.

In other contexts, Lynch’s over-the-top melodramatic emotionalism and fugues of unexplained nightmare imagery can come across as humorous or self-indulgent. Here, though, every excess of style is simply and chillingly apropos. Laura’s father has supernatural, limitless power to hurt her, whether he’s demanding she clean her fingernails at dinner or dragging her into the Black Lodge while possessed by the wood spirit Bob (Frank Silva). The line between reality and supernatural terror collapses not because Lynch is being showy, but because nothing imaginable can be worse than what happens to Laura, who Lee brilliantly portrays as clinging to her own humanity through a veil of drugs, hypersexuality, terror, and overwhelming self-loathing.

When “Fire Walk With Me” was first released, the critical response was shockingly callous; Todd McCarthy at “Variety” actually called Laura—a victim of protracted, repeated, violent sexual assault—a “tiresome teenager.” In recent years, though, the film has begun to receive its due. Though it was pilloried in the past as incomprehensible, it’s past time to see it for what it is: Lynch’s most straightforward film, his saddest, and his best.

I think something was missed about Dune. Yes, the movie has many faults, but lore says that he originally wanted to make it into two movies, but were convinced to make it into one. After presenting a 3 hour version he was forced to cut it to less than 2 hours to match standard movie runtime (those were the days).

Lynch had been specifically hired to direct "The Elephant Man" by the film's (uncredited) executive producer, Mel Brooks. Obviously their styles of filmmaking didn't mesh well...