Has Film Abandoned Sex?

Only if you think all film is the MCU. And if you forget restrictions on sexual content in the past.

A common complaint about the current state of film is that films are now being made for children and adolescents rather than for adults. As a result, the naysayers believe, we’ve desexualized the celluloid.

Director Steven Soderbergh made the most charming version of this argument in February 2022 when he explained that he could not direct superhero films because, “Nobody’s fucking! Like, I don’t know how to tell people how to behave in a world in which that is not a thing.” Film critic Travis Johnson made a less colorful version of the complaint when he responded to a call for less sex in films by tweeting, “one of the longterm outcomes of the systemic infantilisation of mainstream culture is people insisting all culture be suitable for infants.”

Soderbergh is right that superhero franchise films, and current big budget action movies in general, are relatively uninterested in the erotic, or even in the romantic. But Johnson goes too far when he suggests that movie culture is being “infantilized.” In fact, there’s a strong argument that as a whole, film is more open to more different kinds of eroticism than ever before—especially if you consider the erotic experiences, desires, and interests of queer people.

Again, it’s important to acknowledge that the sexlessness of Marvel films is bizarre and extreme. Consider the last two big MCU releases. Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness barely has a romantic plot. To the extent it does, that plot is about how the romantic leads don’t actually know each other and even if they did Dr. Strange would be too afraid to commit to the love of his life or (apparently) to even kiss her.

Similarly, Spider Man: No Way Home is an entire movie devoted to taking one of only two or three couples in the MCU with any spark and separating them in a way that not only ends their relationship, but (literally magically) ends any possibility of romantic tension between them.

This is more than just downplaying romantic relationships or making romantic relationships secondary to the action as in, say, the original Star Wars films. These movies go to ridiculous, almost pathological lengths to banish any lingering erotic tension from the multiverse, erasing personalities and entire realities to avoid anyone suggesting the possibility of someone having sex with someone else. If romance and sex are things you like to see in your stories, watching these films is going to leave you snorting with laughter or irritation. Or, like Soderbergh, with both.

But, despite their best efforts, Marvel films aren’t the only films in existence. Many of those other, non-Marvel films include romance and erotic storylines. More, they include romance and erotic storylines between queer people in fairly substantial amounts. That’s the first time this has happened in basically the entire history of even vaguely mainstream cinema.

Even as recently as thirty years ago, in the mid-1990s, the representation of queer people and queer erotics in mainstream cinema was dire. LGBT viewers had a choice between ugly bigoted stereotypes, as in Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs (1991), condescending mainstream tokenism like Demme’s Philadelphia (1993), and small budget indie films with limited release like Go Fish (1994). Video stores meant that more people could see the last than in previous eras. But still, the pickings were slim.

In contrast, consider the options for viewers interested in queer erotic content today. Moonlight is heir to indie romance films like Go Fish in some ways—but it has substantially higher production values, focuses on Black protagonists, and won the Best Picture Oscar in 2017. That means it is easily and instantly available for streaming to most people with internet access.

The Power of the Dog and Brokeback Mountain, two highly acclaimed mid-budget Westerns driven by gay erotic passion, are also easy to find through multiple platforms. Julia Ducournau’s Titane is less well known, but includes a complicated, angry, painful, sexual, and exhilarating, exploration of gender transition and queer family that simply wouldn’t have been available to most audiences even five or ten years ago.

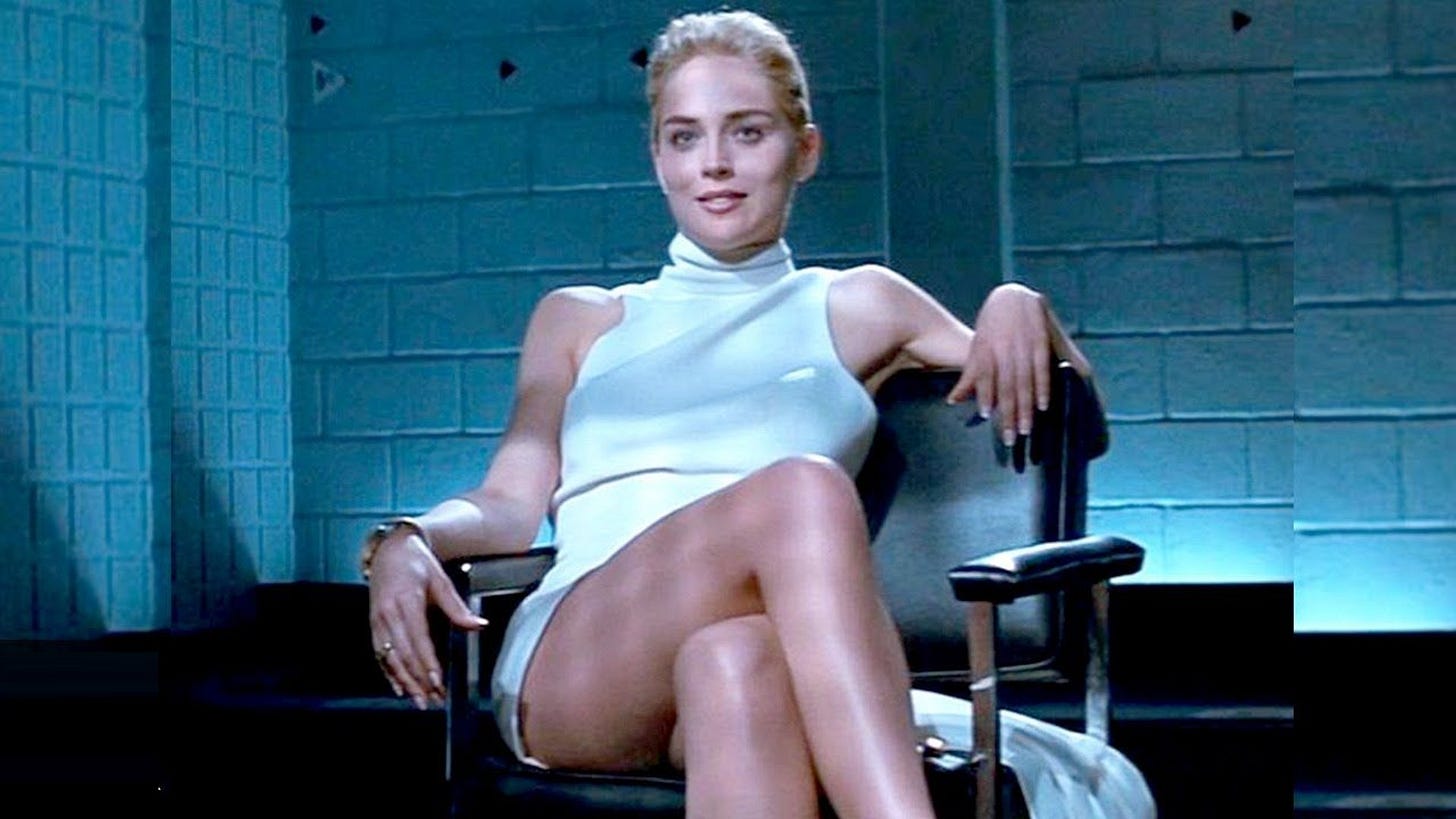

Even those sexless Marvel films have more acknowledgement and more representation of gay sex than any big budget tentpole movie has ever displayed at any point in the past. Multiverse of Madness includes a married lesbian couple with a daughter. You don’t see much of them, but they exist as human beings rather than as prurient exploitation tropes for heterosexual consumption, as per Basic Instinct (1992)—one of the films that often gets cited in lamentations of Hollywood de-eroticization.

The Eternals (2021) goes even further. A major character, Phastos (Brian Tyree Henry) is gay, and he and his husband (Haaz Sleiman) express affection openly, exchange a kiss onscreen, and raise a child together. This is a vastly more extensive, honest, and explicit display of gay sexuality than we were permitted in (as an example) Philadelphia.

For that matter, it’s a more extensive, honest and explicit display of gay sexuality than Disney was willing to put in the MCU just a couple of years ago. And it may be the high point of such honesty, given the current rabid homophobic moral panic targeting Disney by bigoted reactionary politicians like Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. If things are going to get worse, though, that’s all the more reason to acknowledge we are at a high point now.

Some MCU haters and lovers of erotic film might argue that romantic and sexual themes are one thing and LGBT representation is another. Why should a discussion of sex and romance get derailed by all these identity politics?

The fact, though, is that restrictions of erotic content have always, historically, targeted queer people first. LGBT people are always considered hypersexual; a queer peck on the cheek is viewed as more dangerous and more risqué than a straight couple French kissing. That’s why DeSantis’ cowardly and disgusting attacks on LGBT people as a danger to children has gotten traction among people who should know better. And that’s why if film now includes more LGBT representation and more LGBT themes than ever before, then, in important ways that matter, film is more adult, in the best sense, than ever before.

Disliking the MCU and what it represents for film is fine. I mostly dislike the MCU and what it represents for film. But using the MCU to argue for a return to a past that was in many ways more repressive and less imaginative about human possibilities and human love than the present—that’s wrong, and even dangerous. If we’re going to have an adult conversation, let’s have an adult conversation. That conversation should not be focused, first and foremost on whether Dr. Strange can bring himself to kiss the alternate universe double of his true love or not.