How Loving Art Can Make You Hate

On Randall Sandke’s racist history of jazz.

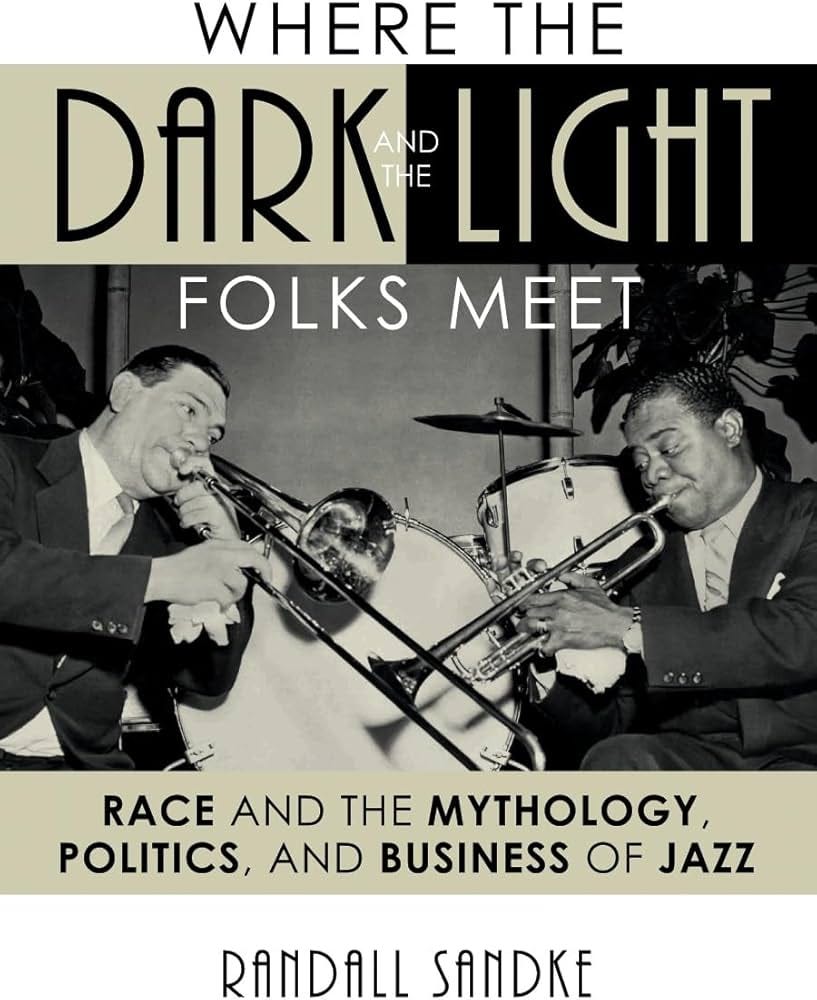

I recently read Randall Sandke’s Where the Dark and the Light Folks Meet, a 2010 survey of interracial influences and collaboration in jazz. I picked it up initially because…well, I was interested in the subject of interracial influences and collaboration in jazz.

But (unfortunately) what I found instead was a case study in how reactionary aesthetics can fuel a reactionary politics. Make American Music Great Again can slide with painful abruptness into a nostalgia for an earlier racist era, and a poisoned resentment of progress—both aesthetic and political. The book ends up as a chilling warning about how even the most well-intentioned nostalgia for an earlier era in the arts can curdle into bitterness and bigotry.

—

This is a post that I would never be able to do without this newsletter. I hope if you find it valuable you’ll consider becoming a subscriber. There’s a 40% off sale now; $30/year. This is a difficult time for writers, and I could really use your help if you enjoy my writing and want said writing to continue.

—

Good intentions…

I say Sandke is well-intentioned because I think he is. His goal is not to deny that jazz is Black music, primarily created by Black people. Rather, he wants to refute and reevaluate myths that frame jazz as a natural expression of Black authenticity.

This idea—that Black performers have innate rhythm, or an innate link to jazz—has, as Sandke notes, been pushed by a range of both Black and white critics over the years, and it ends up in many cases harming and limiting Black creators.

Sandke is not the first to make these points, but his discussion is enlightening and engaging. Performers from Duke Ellington to Miles Davis and beyond have been attacked or shamed for supposedly betraying the authentic African roots of jazz by incorporating complex arrangements or working with white collaborators.

At the same time, critics have often downplayed the eclecticism and adventurousness of jazz musicians. Sandke has fascinating discussions of the ways in which the complex harmonies of popular songs and of classical composition influenced be bop stars (Charlie Parker reportedly carried miniature Stravinsky scores around with him, and would press them on upcoming musicians.)

This is, as I said, more or less the sort of thing that I was hoping to get from the book. But unfortunately, about halfway through the 400 pages, Sandke moves from illuminating the varied sources and geniuses of jazz to excoriating Black people for thinking racism is still a problem.

Road to hell, paved with

Sandke’s disastrous and flatulent descent into reactionary bilge starts when he attempts to answer the question of why jazz has declined as a commercial and (in his view) as an artistic force.

Fans, musicians, and critics are always very interested in trying to figure out the logic behind the ebb and flow of genres and styles. Sometimes you can point to technological changes—the development of long-playing records had a major effect on rock in the 70s; the development of synthesizers transformed popular music in the 80s; etc. Often, though, the evolution of taste just seems driven by chance and by a kind of inevitable churn. Old pop culture sounds old; people want new things. It doesn’t necessarily have to be more complicated than that.

But of course if you’re very invested in a particular style or genre, the eclipse of that style or genre can feel like a betrayal. That’s the case for Sandke, and he has very definite ideas about who has betrayed him. Namely, Black people.

Sandke argues that individual achievement and style was central to the development and appreciation of jazz. But, he argues, after the civil rights movement, Black communities embraced an ethos of victimization and collectivism—or at least, they’re “radical leaders” did.

“The core curriculum was shelved in favor of teaching race consciousness and racial pride,” Sandke says, in a line that could have come from Chris Rufo. And, sure enough, in support of his thesis, Sandke admiringly quotes hack reactionary economist Thomas Sowell (repeatedly), hack reactionary clown historian Dinesh D’Souza, and racist Nazi bile-spewer Ann Coulter.

In a particularly disgusting passage, Sandke sneers at the idea that trumpeter Wynton Marsalis could have ever experienced racism. Marsalis is very successful, you see (more successful than trumpeter Sandke, is the obvious implication) and therefore racism doesn’t exist. It’s like saying that there was no Jim Crow because Louis Armstrong made a lot of money. (Sandke does not say that…but at moments he comes perilously close.)

The reactionary aesthetics of aesthetic progress

Sandke’s dismissal of Marsalis’ experience of racism is pernicious garbage. He, does, though, have other arguments with the trumpeter that are at least somewhat more reasonable. Specifically, he accusea Marsalis of a backwards-looking aesthetic. “Marsalis and his apologists often express a belief that the very concept of jazz innovation is a sham and a distraction from the true nature of the music,” Sandke says. Marsalis wants to stay true to the past, framing jazz as an authentic African-American tradition which must be preserved. Change threatens to undermine its truth.

In contrast, Sandke argues that the truth of jazz has always been individual (interracial) innovation. Sandke frames himself as the true spokesperson for jazz’s colorblind forward-looking roots. But that forward-lookingness is justified as the preservation of tradition. Sandke claims to be progressive, but that progressivism is predicated on reclaiming a past—making America great again.

Sandke’s nostalgia comes into high relief if you remember that jazz is not in fact the only music in America, much less on the planet. Remember, Sandke’s thesis is that Black radicalism/Black nationalism undermined a faith in and appreciation of musical innovation, dooming jazz. The implication here is that musical innovation can only take place within jazz; no other music, apparently, is truly innovative; all other Black music of the last 60 years has been worthless uninnovative dreck.

Of course, Sandke never says that so baldly, because if he did he’d look like a fucking fool. Are we really supposed to believe that Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson, Donna Summer, Beyoncé, to say nothing of Jlin, Virginia Rodrigues, or ESG, were not innovators and not individuals because they weren’t categorized as jazz? For that matter, what about the entire genre of hip hop, which reappropriated and refashioned jazz itself through sampling in stunning, original ways?

Sandke presents himself as a daring musical listener, whose taste is unbounded by concepts of race or by the dead weight of the past. Yet, he seems to have no interest in, knowledge of, or appreciation of any musical trend or movement of the last 50 years at least; he pointedly ignores fusion, for example, despite it being the jazz subgenre that perhaps best validates his argument for interracial collaboration. The further you get in the book, the more you feel like you’re being hectored by some grandpa bellowing at the kids to get off his lawn.

Black people don’t owe you the music you liked as a kid

That bellowing is familiar. Sandke’s argument has close parallels in the seemingly never-ending excoriation of contemporary film. Like Sandke, critics like Martin Scorsese attack contemporary artistic production because it’s not innovative the way art was innovative fifty years ago. Reactionary evocations of a past golden age are couched in the language of progress and innovation. Grandpa longs for the old days, when everything was new.

I’m not arguing that all movies and all music today are awesome, or that the industry is wonderful for all. Streaming platforms are exploitive; a lot of contemporary pop is pretty boilerplate; Marvel superhero movies suck. But recognizing the limitations of the current landscape shouldn’t make us overstate the awesomeness of an earlier age in which (for example) women had basically no opportunities at all to direct films and/or Black people were systematically prevented from attending clubs where Black musicians played.

Sandke repeatedly acknowledges the racism of the early days of jazz and insists that he is opposed to discrimination. And yet, he constantly trumpets the virtues of integration in the early jazz scene, and insists over and over that Black artists were not materially worse off than their white counterparts. He downplays that exclusion of Black performers from studio and film work, suggesting that jazz artists didn’t really want those gigs anyway. And he entirely ignores the extent to which Black artists were targeted by government; Billie Holiday and Hazel Scott both, for example, had their careers devastated by the Red Scare—which was also, of course, a racist panic.

The downplaying of racism past leads inevitably to downplaying of racism present. In the ugliest passage in the book, Sandke embraces proto-Trumpist anti-DEI rhetoric, asserting with his whole chest that white musicians like him are now the ones who really suffer from racism.

The balance of power has shifted so that now, in an age of racial redress, black skin can entitle its bearer to preferential treatment in many areas of education and employment. The liberal notion of equality has been supplanted by race-based initiatives that seek to tip the balance in favor of minorities who have been historically disadvantaged.

This is whiney racist horseshit. Sandke should by all rights be embarrassed to think this drivel, much less put it in print.

He’s not embarrassed, though, because he is buoyed not just by the babbling of white supremacist assholes like Ann Coulter, but by his high estimation of his own aesthetic taste. Sandke is a very knowledgeable, very thoughtful commenter on (early) jazz. But his very knowledge and expertise becomes a trap. He can hear the brilliance of both Charlie Parker and Lennie Tristano, and he thinks that that gives him the authority and the insight to dismiss entire musical decades and genres, and to make sweeping claims about racism and discrimination based on his deep reading of Dinesh D’Souza.

Or to put it another way—as Gamergate showed, fandoms create a powerful sense of expertise, of entitlement, and of nostalgia, and that mixture can very easily be weaponized on behalf of reactionary political programs. In a white supremacist society, the claim that “no one is making the stuff I like anymore” slides easily into a longing for an earlier era characterized by less equality, more segregation, and fewer opportunities for Black people, women, and other marginalized groups.

Of course, Sandke frames that earlier era as one of greater racial amity and meritocracy. That’s standard procedure; we were all happier back then before the irresponsible radicals started to make demands on pure-hearted, meritocratic white trumpet players. Yes, Black and white folks have always met, and always made music together. But that alone is not, unfortunately, enough to defeat racism. On the contrary, as Sandke’s book demonstrates, even the love of music can, under the right circumstances, become a spur to hate.

Ugh, sooo sick of racists with inflated “estimation(s) of (their) own aesthetic taste” spewing their bullshit beliefs. Hatred is fucking boring and teeeedious, and it’s clear to me it’s why humanity can’t have nice things.

Anywho, plenty of lines I’ll want to be citing you for in this one, but my favorite is “Grandpa longs for the old days, when everything was new”

Hm…

Quaffed down 400 pages of mixed insights and hatred from a frustrated racist, then served up an unsparing, astute analysis of the whole for a pretty good read.

Write some more!