How Trump Changed the Way I Look At The Old Masters

Grünewald as MAGA foreshadowing

All art exists in time. That’s a truism which is often deployed as simplistic apology, as if criticizing Shakespeare’s antisemitism is an offense against context, scholarship, or history itself. But the truth is that to say art exists in time is to acknowledge that The Merchant of Venice exists now, as well as then. We see Shylock through out own time; how else could we see him? We can’t go back to Jacobean London.

Grünewald vs. Grünewald

The great art critic John Berger in a lovely essay on the German painter Matthias Grünewald explains that seeing past context as the only context is a kind of arrogance. It suggests, falsely, that they are time bound, while we are free.

It is a commonplace that the significance of a work of art changes as it survives. Usually, however, this knowledge is used to distinguish between ‘them’ (in the past) and ‘us’ (now). There is a tendency to picture them and their reactions to art as being embedded in history, and at the same time to credit ourselves with an over-view, looking across from what we treat as the summit of history. The surviving work of art then seems to confirm our superior position. The aim of its survival was us.

This is illusion. There is no exemption from history.

Berger goes on to say that when he first saw Grünewald’s stunning Isenheim alterpiece in 1963, he viewed it as a record of despair and fatalism. His early thoughts focused mostly on the crucifixion and the representation of mangled flesh. For Grünewald, Berger wrote in the early 60s “disease represents the actual state of man. Disease is not for him the prelude to death – as modern man tends to fear; it is the condition of life.”

In 1973, however, when he went back to the altarpiece, Berger saw Grünewald’s use of light as expressing a transcendence of illness, disease, and misery. The art hadn’t changed, Berger says. What had altered was Berger himself.

In 1963, Marxist revolution and change still seemed to Berger possible, and Grünewald’s in that context expressed a retrograde fatalism—powerful, lovely, but not especially relevant. In 1973, in contrast the French protests of 1968 had been crushed. Change seemed elusive, and even impossible. From Berger’s new, more dour perspective, Grünewald’s Christian depiction of death and resurrection felt like it was “miraculously offering a narrow pass across despair.”

Christ vs. Christ

Berger’s essay made me revisit Grünewald’s altarpiece, and in particular the Crucifixion scene. And it also made me realize that, like Berger, my view of the artwork (or of its reproduction, since I, unlike him, have never seen it in person) has changed considerably.

I first saw Grünewald’s crucifixion in an art history course when I was in college. At the time I enjoyed a lot of Christian art even though I was Jewish. Or, perhaps, to some degree I enjoyed it because I was Jewish; Christianity wasn’t imposed on me at home, and so I didn’t find Christian iconography oppressive or threatening.

In any case, I loved the painting, both for its incredibly, extravagantly gruesome and twisted Christ, and for its bizarre use of scale. The image depicts, or riffs on the passage “He must increase, but I must decrease.” Like much medieval European iconography, Grünewald painted most important figure (Christ) at a larger scale than he paintedeveryone else. Grünewald takes this medieval symbolism, however, and applies it to a more realistic image, arranging the figures so that they seem to be spiraling down around the Cross, diminishing to nothing.. It’s a powerful representation of human inadequacy and powerlessness before death and before God.

Time passed, as it does, and after some thirty years of increasingly militant and increasingly ascendant Christofascism, I’m a lot less able to see Christian iconography as a purely apolitical aesthetic. Grünewald may have been expressing truths about the human condition; he may have been offering despair, he may have been offering hope; he may have been talking about human powerlessness and human incapacity. But he was also lending his talent and his genius to buttress a state religion, and to trumpet the magnificence of a particular ruling ideology.

Or to put it another way, when I look at the altar now, it’s hard for me not to think, “What were Jewish people in Germany supposed to think of this altar? What were Christians supposed to think about Jews or about Muslims when they saw it? What did the altarpiece, painted between 1512 and 1516, have to say to Europeans carving out colonies in Africa and the Americas?

Berger in both his readings sees the altarpiece as addressing universals; the Christian content is bracketed. That’s how I saw the altarpiece at first too. Grünewald was of his time, and so he was creating Christian iconography out of his faith. But (as a modern person, freed from time) I was able to have a personal response to that icnonography that didn’t touch on faith. The giant crucifix wasn’t, after all, speaking to me, really. It wasn’t a threat.

Now, though, I’m forced to ask the question—what if it is? The image of Christ, grotesque and dead, rising above all these lesser mortals, who kneel and shrink before him—that’s a powerful representation of a threatening, gruesome hierarchy, imbued with aesthetic and spiritual force. It shows that humans are nothing without Christ, which leaves, say, Jewish people, or indigenous people in the Americas, in an awkward, and dangerous, position.

Christ is death and power and despair and hope. Christ is huge. Everyone else, without Christ, and before Christ, is spinning vertiginously towards nothing. And while that might be meant to inculcate humility in Christians, it’s easy to turn humility to something less benign when you’ve got a system whereby the humble can see exactly who, down there, is further from Christ, and exactly who is smaller than you.

Christ is everywhere

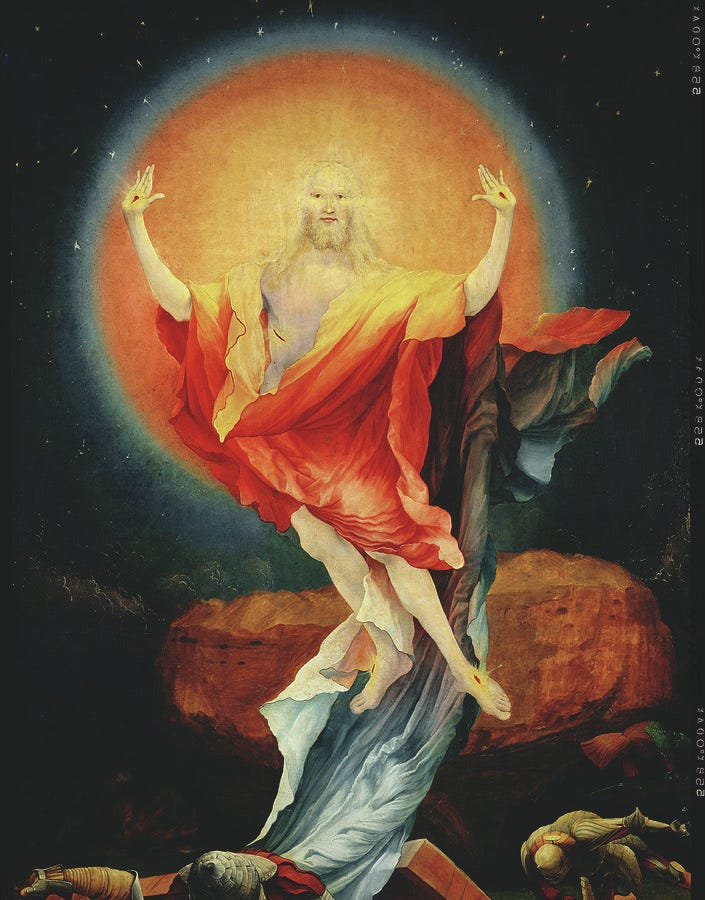

It’s not just this one image, either. When you start thinking about Christian iconography as a projection of power instead of (or as well as) an expression of faith, a lot of the great art in the European tradition takes on a certain ominous malevolence. Grünewald’s own Christ risen could be transcendent, but it could also be the moment before the supervillain starts incinerating people with laser beams from his head.

Similarly, Berger in his essay collection Portraits, discusses Bosch’s hell as a prescient vision of claustrophobic neoliberal globalization. But you could also see it as a reiteration of Christian supremacy and Christian hierarchy, in which disbelievers, heretics, and outsiders are cast into a nightmare no-space for the enjoyment of those who control both the boundaries of this world and the next.

Even something like Piero Della Francesca’s The Resurrection has a queasy MAGA resonance. Berger lovingly analyzes the painting in terms of its careful construction, composition, and perspective: the men lying in front of the risen Christ form a triangle, he argues, with Christ’s hand at the apex, so that as he lifts up his robes he is drawing them to him, like fish in a net.

Francesca “paints what the world would be like if we could fully explain it,” Berger says. But how do you separate that complete, totalizing explanation from the complete, totalizing authority that is supposed to impose it? Christ’s six-pack, his perfect physique, that banner in his hand, are reminiscent of latter-day military statuary and of nationalist kitsch. It’s not hard to imagine some MAGA acolyte putting Trump’s head on that magnificent torso (though they’d have to clean up the wound, I guess.)

Time will take you on

Grünewald as enforcer of Christofascist hierarchy isn’t the one, true interpretation of the Isenheim alterpiece any more than Grünewald as poet of despair or Grünewald as poet of hope is the one, true meaning of the work. Different times, and different people, see different things in great art; one vision doesn’t need to reduce, or supplant, another. Great art is multiple.

And yet, it’s also true that great art is singular. It bends time around itself, simply by persisting and demanding attention over decades or centuries. Berger looked at the same image I did, and then looked at it again. Younger me saw it, and then here I am looking once more. Meanings change—and also they don’t. Christianity then signified, among other things, the political and financial power to impose a vision on the present and the future—a vision of who is most important, and who vanishes into their own insignificance.

What is considered timeless, what is considered universal, to what we must bend our eyes and our knees, no matter the age or the place—that’s all a function of history and of time, too. You’d like to feel that we’ve moved on to a broader, more enlightened world, with more space for us all to stretch and expand. But sometimes the clock ticks and decades go by and you find yourself looking up at that same dead cross, which wants to diminish you.

Yes, I have, unfortunately, the same reaction now to some of the great European cathedrals. When I was younger I could soak in the beauty and awe they inspired. But when I’ve had a chance to visit some more recently, they feel like monuments to murder and oppression and colonialism and I feel eager to get away.

"the great art in the European tradition takes on a certain ominous malevolence" Yes it does.