Intent Is Central to the Definition of Genocide

But should it be?

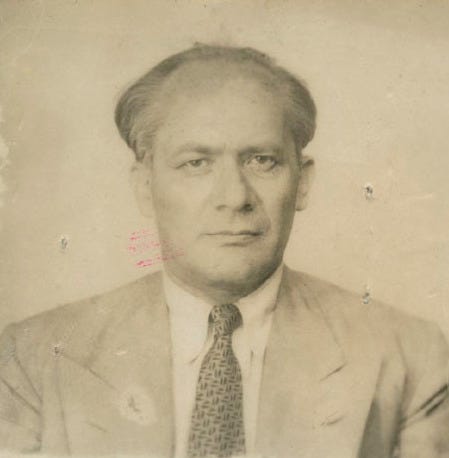

Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term “genocide” and was instrumental in establishing the UN genocide convention.

Experts consulted by the UN have said that there is currently “a risk of genocide against the Palestine people.” Over 800 scholars signed a statement warning of “potentially genocidal intent.” Among other comments, they pointed to Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant’s declaration that “Gaza won’t return to what it was before. We will eliminate everything.” They also singled out Maj. Gen. Ghassan Alian’s address to Gaza residents in which he said, “Human animals must be treated as such. There will be no electricity and no water, there will only be destruction. You wanted hell, you will get hell”.

The experts’ statement has, of course, not ended the discussion. There continues to be a vigorous and bitter debate in the media and on social media about whether Israel’s actions constitute genocide, war crimes short of genocide, or a proportionate response to the Hamas terrorist attacks.

Intent defines genocide

My own view is that if the UN says there’s a risk of genocide, it’s reasonable for people to refer to the current Israeli attacks as a genocide which we need to halt immediately. But others have been arguing back and forth on that issue, and I don’t think I can lay out the issues better than they have.

I did want to talk a little though about the focus in much of the discussions of genocide on intent. Genocide, in general discussions and in law, is a crime closely tied to the question of motive. A genocide is not just a killing, but a killing with the intent of destroying a people. Per the 1948 UN genocide convention:

genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, [highlight mine] a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its

physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

The acts listed here—killing members of the group, causing serious bodily harm, deliberately inflicting conditions calculated to bring about physical destruction—are bad in themselves, and in many situations would be war crimes. But they don’t reach the status of genocide unless there is an intent to destroy the group in whole or in part.

To determine whether an act of genocide is committed, per the convention, you need to know not just what was done, but why it was done. Just as, before concluding that racist discrimination exists, you need to refer, not to the experience of the person discriminated against, but the motive of those discriminating.

The problem with intent as a standard

If you stopped at that last sentence and said, “Hey, wait a minute…”—well, you should have. In discussing discrimination, many scholars (such as Kate Manne and Victor Ray), have argued that you should not focus on the motives of the perpetrators.

Racism is not, Ray says, or at least not just “a special category of meanness.” Rather, racism can be “perpetuated through conscious intent, unconscious bias, or policies and practices that privilege one racial group over another.” And Ray adds, “Once biases are built into seemingly legitimate social sorting mechanisms, no ill intent is needed—following the rules reproduces racial inequality.”

There are a couple of reasons why scholars warn against focusing on intent in discussions of racist discrimination.

First, intent is extremely difficult to parse at the best of times, and becomes virtually impossible to pin down in situations where people are likely to lie. Everyone is well aware at this point in history that racist discrimination and prejudice are frowned upon. In employment law in the US, for example, you are generally allowed to fire people for basically any reason other than prejudice towards a protected class. Employers therefore have a huge incentive to deny they are motivated by racial animus.

Second, and relatedly, as Kate Manne discusses, the focus on intent tends to center discussions of racism or misogyny on the internal state of racists or misogynists, instead of on the experiences of those facing bigotry. Rather than trying to figure out what misogynists think or feel, Manne argues, we should evaluate whether an action is misogynist based on how it “would be interpreted by a reasonable woman on the receiving end of it.” Manne argues that “Hostility which is expressed but not consciously experienced as such can therefore count as real hostility, on this way of thinking about it.” We should treat the targets of bigotry as the experts in bigotry’s effects, rather than deferring to bigots as the authoritative source on whether bigotry and violence exist.

These issues with intent and discrimination are also relevant when it comes to addressing and prosecuting the extreme form of discrimination known as genocide. Scholar Katherine Goldsmith writes:

In terms of preventing further atrocities and stopping genocide, proving a perpetrator's state of mind is a massive problem. Perpetrators are fully aware that admitting what they are doing could interfere with achieving their objective. They are therefore unlikely to admit what their intentions are and thus risking possible action against them, especially if the objective of destroying the target group is still taking place.

Goldsmith (writing in 2010) argues that focus on specific intent hobbled convictions for genocide in Srebrenica. Goran Jelesic admitted to beating and executing Muslims, and he had expressed anti Muslim bigotry. He had even referred to himself as the “Serbian Adolf”. But the International Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) decided they did not have evidence that he had specifically intended to exterminate all Muslims, and so they found him not guilty. An Appeals Chamber found this decision was wrong, but Jelesic was not retried. He received forty years for other crimes, but Goldsmith argues, “he was still not convicted of the crime he committed, which is unacceptable.”

You can see the confusion caused by intent in ongoing debates about what does and does not constitute genocide as well. Historians agree that Stalin’s policy of collectivization and nationalization was responsible for the 1932-33 famine in Ukraine that killed millions horribly through starvation. They also agree that he was determined to crush “Ukrainian national counterrevolution”, and that he engaged in a campaign of oppression and political violence against Ukrainian intellectuals, church officials, and other leaders.

But while many historians see this as a classic example of genocide, others hesitate because Stalin’s intent is still somewhat opaque. Yes, he wanted to eliminate Ukrainian national identity; yes he policies which led to the terrifying, sweeping starvation of Ukrainians. But how do we know that he meant to wipe out the Ukrainian people via starvation? Absent a full taped confession, can we ever really know a genocide is a genocide?

Denying denial

Scholars often argue that the final stage of genocide is not the genocide itself, but its denial. “The perpetrators of genocide dig up the mass graves, burn the bodies, try to

cover up the evidence and intimidate the witnesses. They deny that they committed any crimes, and often blame what happened on the victims,” writes scholar Gregory H. Stanton.

Denial allows perpetrators to escape justice. It also sets the stage for further violence and discrimination, as victims are persecuted for discussing what has happened to them and targeted anew for their refusal to forget.

Framing genocide around intent, as we’ve seen, makes denial as easy as simply saying, “I didn’t mean it.” If the only final evidence of genocide is in the minds of the murderers, then murderers have the final say about whether genocide occurred…and it is in their interest to deny it.

Goldsmith and other scholars have argued that we could get around this problem by moving from a definition that relies on specific intent to one that relies on what she calls a “knowledge-based” approach. In a knowledge-based approach, a person would not need to intend the destruction of a group in whole or in part. They could be “guilty of genocide if they willingly commit a prohibited act with the knowledge that it would bring about the destruction of a group.”

The knowledge-based approach addresses the problem of conviction in court of lower-level functionaries in a genocidal plan. It still encourages us, though, to focus on the inner state of perpetrators rather than on the experiences of those targeted.

Which seems especially problematic when combined with the tendency for people committing atrocities and their allies to delegitimize the voices of those they are targeting. President Joe Biden did just that last week when he claimed that he had “no confidence” in the death toll figures from Palestinian health officials. Biden did not explain why he doubted the figures when the international community has relied on them for years. (Palestinian health authorities said more than 6000 civilians had been killed as of last week).

Can you address genocide without intent?

Ideally, it would be possible to say, “this is a genocide” without focusing on intent, the way that you can say, “this is discrimination” in many situations even if you don’t have specific evidence of motive.

You can look at segregated school systems, and the history of racist practices around schooling, and the experiences of students in segregated schools, and you can say, “this is racist discrimination,” without having to read the private correspondence, or the mind, of school superintendents, school boards, or parents. You can look at Hamas’ horrific murder spree and say, “this was a war crime,” without having to parse whether the people who committed them saw themselves as murderers or freedom fighters. Maybe we should also be able to look at the history of apartheid and discrimination in Israel, and at Israel bombing supposed “safe zones”, or dropping 6000 bombs in a week, and say, this looks like an effort to destroy a people in whole or in part, whatever the intention may be.

Or maybe that’s unworkable. I don’t have a definite answer. It does seem wrong to me, though, that the worst form of racist violence is defined so centrally by individual motivations when we know that racist violence works through structures, through complicity, and through the deniability afforded by our obsession with individual motivations.

It’s hard to stand with victims if you’re primarily focused on entering into the skulls of victimizers. The concept of genocide was meant to provide a framework to remember and to hold perpetrators accountable. But I worry that, with its elevation of intent, it may sometimes, in some conflicts, have become a way to exculpate and forget.

::It does seem wrong to me, though, that the worst form of racist violence is defined so centrally by individual motivations when we know that racist violence works through structures, through complicity, and through the deniability afforded by our obsession with individual motivations.::

To really mangle a quote, "It is nearly impossible for people to see injustice when their well-being requires their denial of its existence."

I KNOW there's a quote where this is said a lot better than I just did! I just can't find it....

This rather perfectly ties into a YouTube series I'm watching, "COPAGANDA" by television critic Skip Intro (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=udhDawfCLHo&list=PL2ac8vr2QyTdlWwd8OQIc1it6bAfMGPPC ). In the series he talks about how television has traditionally lionized the police as "a thin blue line" between decent people (or if we're being honest, Middle-Income White viewers!) and the hordes of (usually not-White and certainly not Middle-Income!) rabble that would burn everything to the ground. Whenever you see Bad Cops, they're always presented as "Bad", as in "outside the normal protective norm of the GOOD police!". Even shows that want to interrogate what being a "Good Cop" means tend to fall back on the tropes of the morally upright/incredibly driven Good Cop versus the corrupt/bigoted/lazy and incompetent Bad Cop who gives the force a bad name.

Contrast that with the cops who used military-grade hardware to remove Occupy Wall Street—a collection of unwashed, smelly, but peaceful protesters who set up a tent city in the Wall Street district as a way to shame Mayor Mike Bloomberg (an outright Billionaire and owner of a media empire as well as a financial, software and data company) and his Capitalist cronies; or the police in Uvalde, TX who courageously, and with no regard for their personal safety in the line of duty...just waited outside Robb Elementary School while eighteen-year old shooter Salvador Ramos proceeded to kill nineteen students and two teachers, while wounding seventeen others, before they finally bothered to go in and shoot him dead. This doesn't even cover the victims shot by police for Existing While Black.

How this ties into your piece, Noah, is that cop shows never see corruption, bigotry, laziness or incompetence as systemic—same as those who, when they throw around the term "genocide", tend to look for one person, or at most a group of persons, responsible rather than the system that made them possible. I think this is important because it shows how deep the desire to blame an individual over a system goes....

Wouldn’t genocide be more analogous to “hate crime” than to “discrimination”?