Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Jolene

Different versions, and different identities, in Parton’s classic song.

My apologies for the formatting error in an earlier version of this post. It should be fixed now.

Beyoncé’s cover of Dolly Parton’s 1973 “Jolene” initially appears to be a kind of inversion or refutation of the original. Parton’s song is a desperate plea to the other woman (“I’m begging of you please don’t take my man”); Beyoncé’s is a cold threat (“I’m warning’ you, don’t come for my man.”) The two singers lean into their very different personas—Dolly as virtuous rural woman, Beyoncé as “Creole banjee bitch” who takes no shit.

The Good Old Days When Times Were Bad

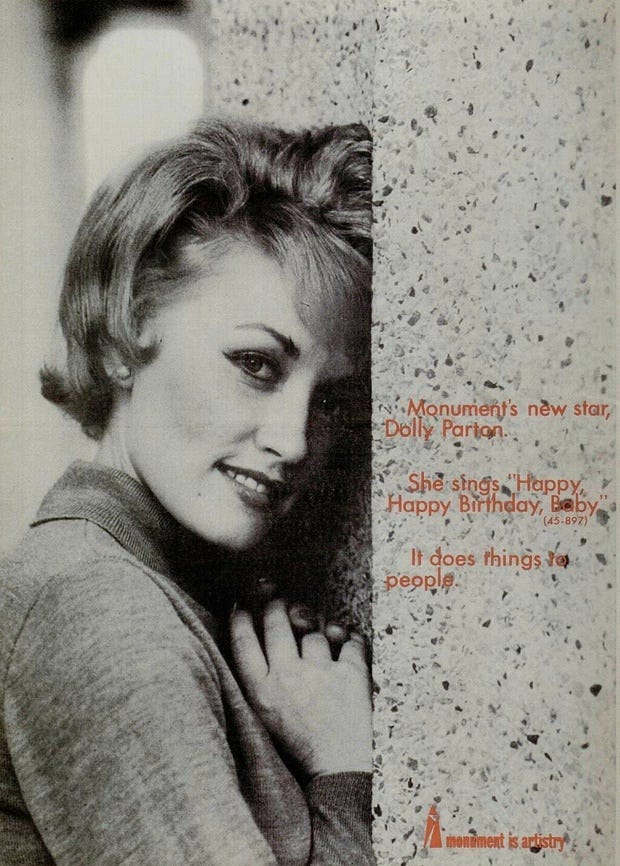

If you paused a second there and said, “Wait—Dolly’s persona isn’t virtuous rural woman!”—well, I think that’s kind of the point. Parton’s had a long career, in which she’s variously embraced the image of demure rural wife, rejected it, and played with it. In her 1969 song, “In the Good Old Days (When Times Were Bad),” for example, she references and to some degree cosigns country’s nostalgia for a rural past while also emphatically rejecting it.

I've seen Daddy's hands break open and bleed

And I've seen him work 'til he's stiff as a board

And I've seen Momma lay and suffer in sickness

In need of a doctor we couldn't afford

Anything at all was more than we had

In the good old days when times were badNo amount of money could buy from me

The memories that I have of then

No amount of money could pay me

To go back and live through it again

Parton loves her parents and wants to be true to them—but at the same time, being poor sucks. Who wouldn’t rather wear sparkly gowns and a big blond wig and be a star?

I think this ambivalence is very much a part of “Jolene” as well. Jolene is after all an attractive figure.

Your beauty is beyond compare

With flaming locks of auburn hair

With ivory skin and eyes of emerald green

Your smile is like a breath of spring

Your voice is soft like summer rain

And I cannot compete with you, Jolene

More than one listener familiar with Parton circa 1974 has commented, “Good lord! If Parton looked like that, what did Jolene look like?!” Parton says “I cannot compare with you, Jolene” but anyone who has ever seen photographs of Parton—and indeed anyone hearing her intimate, sensuous twang—is bound to make that comparison, and not necessarily to Jolene’s benefit.

If Parton is a sex bomb (and of course she is!) then her position in the song becomes destabilized. Is she the innocent girl from the good old days who’s afraid of someone stealing her man? Or is she identifying with, and in the position of, that other woman? When she sings to Jolene that “your smile is like a breath of spring/ your voice is soft like summer rain” is she singing to some other woman? Or is she looking in the mirror?

Girl Crush

Jolene is a song about envy, but envy, desire,and identification are often difficult to separate. In “Jolene” the singer explicitly contrasts herself with her rival. But in the course of that contrast she also expresses a yearning to be her rival, and perhaps to be with her rival—as Little Big Town makes clear in their almost-certainly-“Jolene”-inspired half-out-of-the-closet hit “Girl Crush.”

I want to taste her lips

Yeah, 'cause they taste like you

I want to drown myself

In a bottle of her perfumeI want her long blond hair

I want her magic touch

Yeah, 'cause maybe then

You'd want me just as much

“Jolene” is indelible in part because Parton’s investment is not straightforward. She’s the dutiful wife, but she’s also the other woman. She’s Jolene’s rival, but she’s also Jolene’s admirer, and she’s also in some sense Jolene herself. The song is about her vulnerability, but it’s also about her desire, and about imagining herself as that other woman. Gloria Ann Taylor’s paranoid, ecstatic cover (also from 1973) captures the song’s bifurcated dynamics, when Taylor breaks into cries at the end that could be moans of pain or orgasmic wails.

I’m a Woman Too

In that context, Beyoncé’s tough-as-nails version seems less like a reversal and more like an exploration of and reemphasis on elements already in the original song. Parton presented herself as vulnerable victim in a way that suggested she might not be just the vulnerable victim. Beyoncé presents herself as an invulnerable, unstoppable force in a way that (especially given the comparison with Parton’s original) can’t help but make you wonder whether she is in fact as invulnerable as she would like you to believe.

Jolene, I'm a woman too

The games you play are nothing new

So you don't want no heat with me, Jolene

We been deep in love for twenty years

I raised that man, I raised his kids

I know my man better than he knows himself (uh, what?)

I can easily understand why you're attracted to my man

But you don't want this smoke

So shoot your shot with someone else (you heard me)

The lyrics here are semi-autobiographical; Beyoncé is talking about her relationship with Jay-Z. Their marriage has been long-lasting, but there have also been rumors about Jay-Z’s infidelity. Beyoncé’s “Jolene” refuses to identify with or express jealousy for the other woman, as Parton’s version does. Instead, Beyoncé identifies with her man.

In doing so, though, she sounds in some ways less powerful and more defensive. Parton’s willing to play with the idea of being the other woman and of wanting the other woman in ways that Beyoncé is obviously uncomfortable with—perhaps because of the limits of her public persona, perhaps because she’s less comfortable with the queer connotations, perhaps because identifying with an iconically white interloper is more fraught and less appealing.

You could say that Parton projects weakness to hide her strength, while Beyoncé projects strength to hide her weakness. I don’t think that’s exactly accurate, though. Both versions of “Jolene” use confessional as a trope, but it’s a trope, not a window into anyone’s soul. Parton and Beyoncé use the imagined love triangle to explore the ways in which women’s relationships with each other are framed around and by relationships with men. Strength and weakness, love and lust, desperation and desire between women all have to be sung about, thought about, and/or experienced as a part of heterosexual love.

Beyoncé’s song is also about the relationship between Parton and Beyoncé, and between Beyoncé and the country music genre. Parton introduces Beyoncé’s version of the song with a short spoken intro:

Hey, Miss Honey B, it's Dolly P. You know that hussy with the good hair you sang about? Reminded me of someone I knew back when, except she has flamin' locks of auburn hair, bless her heart. Just a hair of a different color but it hurts just the same.

Parton references Beyoncé’s song “Sorry” from her album Lemonade: “He only want me when I’m not there / He better call Becky with the good hair.”

Parton is creating a different triangle here, in which Beyoncé and Parton are united against the third woman—Becky or Jolene. That unity is also across genres, as Parton suggests that Beyoncé’s music has continuities with country that precede her “Jolene” cover. Dolly and Beyoncé have the same experience of pain and heartbreak—and of disdain for homewreckers and Other Women.

A unity among women built in part on rejecting certain other women remains a nervous unity though. Parton’s insistence that she and Beyoncé share a common “hurt” seems to inadvertently reject Beyoncé’s de-vulnerablizing of “Jolene. For that matter, it inadvertently rejects the pretense in “Sorry” that Beyoncé “ain’t thinkin’ bout you” when she’s clearly thinking about the guy.

Black and White and Jolene

By the same token, when Parton welcomes Beyoncé into country music, she can’t help but evoke the ways in which country has rejected Black performers over the years even while building on and appropriating Black musical contributions. “Jolene,” sung by a Black woman, has a not-very-buried racial dynamic which mirrors or comments on the way country music, and the country of America, has consistently betrayed and cheated on Black women and Black people. That’s why Beyoncé specifically says that she’s a woman too; since Sojourner Truth, Black women have often been denied femininity even as they’ve been denied American identity.

That’s made explicit in Chapel Hart’s video “You Can Have Him Jolene,” where the thin white woman gets the guy and the fat Black singer and her friends end up in jail.

Chapel Hart’s lyrics suggest that the man doesn’t deserve either Jolene or the singer; both the woman and the other woman are joined in the realization that men (and the patriarchy) suck. When the other woman and the man are visualized as white in the video, though, the tentative bridge between the two breaks down—not least because the white woman can call in the police to enforce her claims (to innocence, to femininity, to men, to country music) and the Black women can’t. After watching “You Can Have Him Jolene,” Beyoncé’s “I’m gonna stand by him/he’s gonna stand by me” comes across as a (perhaps overly hopeful) declaration of racial solidarity based in part on a sense that solidarity from white women will not be forthcoming.

“Jolene” is, of course, a plea for solidarity between women—solidarity which forms a potential bridge between weakness and empowerment, desperation and determination. Beyoncé, Gloria Ann Taylor, Chapel Hart, and Little Big Town, and Parton herself, all shuffle those terms to explore the possibilities and limits of a range of racialized female identities and positions. The song is great not because of Parton’s vulnerability, but because vulnerability is only one of the possibilities the song offers. When Parton, or Beyoncé, sings “Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Joleeeene,” they’re referring to (at least four) different people, some of whom may be themselves.

Hi all. Very sorry for the formatting mess up with this post. I am not sure what happened, but sections repeated. It should be fixed now.

Prepare to have your mind blown:

Debbie Harry is several months older than Dolly Parton