June Jordan & the Erotic Politics of Being In The Wrong Place

On “A Sonnet From the Stony Brook”

June Jordan is best known as a political poet, and after that perhaps is best known as an erotic poet. Sometimes, rather marvelously—and not unusually for queer poets—she was both. A case in point is her wonderful albeit little analyzed poem “A Sonnet From the Stony Brook.”

A Sonnet from the Stony Brook

Studying the shadows of my face in this white place

where tree stumps recollect a hurricane

I admire the possibilities of flight and space

without one move towards the ending of my pain.

I conspire with blackbirds light enough to fly

but grounded by the trivia of appetite

I desist decease delimit: I deny

the darling dervish from a half-forgotten night

when mouth became a word too sweet

to say aloud and body changed to right

or wrong ways to prolong new irresponsibilities of heat

new tunings of a temperature with weight and height.For all I can remember all I know

only shadows flourish; shadows grow

—

I love writing about poetry, but poetry criticism doesn’t exactly have a huge audience. So! If you are one of the few who like this sort of post, consider encouraging me by becoming a paid subscriber. It’s $50/year, $5/month.

—

Erotic reading

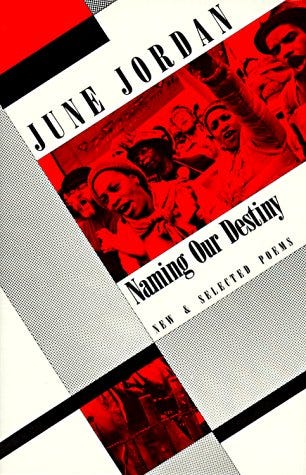

This poem appears in Jordan’s 1988 volume Naming Our Destiny, close by a number of other poems about a difficult long-distance relationship. In “A Sonnet for a.b.t.” she writes about “the 65 miles that would irk/or exhaust a fainthearted lover”. In “Romance in Irony” she pens the frustrated double entendre “I lie in bed/fingering photographs from Colorado”.

Given that context, it’s possible to read “A Sonnet for Stony Brook” as a conflicted, perhaps slightly self-mocking, poem about lost love and grief. Jordan, who was then a teacher at the University of Stony Brook, NY, east of New York City, sits (on campus?) watching trees broken off in a hurricane (a wry, ironized castration metaphor, perhaps) and grounded black birds who would rather eat than fly. “The possibilities of flight and space” are tantalizing but denied; the line, “without one move towards the ending of my pain” is lengthy and deliberately clunky. “Pain” lands like a discordant tree dropping off its stump, startling and slightly ridiculous, but only the more unpleasant for that.

The heart of the poem flies away (unlike the blackbirds) from the disappointing present, back to an erotic idyll which is only intensified by Jordan’s emphatic alliterative disavowal (“I desist decease delimit: I deny.”) Jordan remembers “the darling dervish from a half-forgotten night” who is, clearly, not forgotten at all. The focus of this sweaty not-forgetting is the “mouth”—a particularly charged location for lesbians and for poets. Love and sex is “a word too sweet/to say aloud” even as she says it. Words become memory become bodies (“to say aloud and body”), prolonging (“right or wrong”) weight, height, heat—all framed as “irresponsibilities” which should be left out of memory and out of a respectable poem.

The last lines slide, erotically and anti-erotically, out from and into ambiguity. Jordan again insists that her memory and her knowledge have blanked out her lover and the night in question, even as lust and love and longing underline and shadow those denials. “Only shadows flourish; shadows grow” is an acknowledgement of erasure—the campus, the trees, the birds, the past, are all lost in a dark nothingness. But it’s also an assertion of the impossibility of erasure, since the shadows here are Jordan and her lover, the twined words and bodies which make her poem, herself, and her world.

Politic reading

Shadows, here, are an inescapable eroticism. At the same time, the erotic is shadowed, or doubled, or implicated in, a politics of race and gender.

The first line of the poem immediately references race:

Studying the shadows of my face in this white place

The whiteness could refer to snowfall, or to the pale color of the stumps, perhaps. But it also pretty clearly refers to the racial makeup of university campuses in general, and of Stony Brook in particular.

Similarly, when Jordan refers to “the shadows of my face,” she might be talking about tree shadows falling across her, or she could be foreshadowing (as it were) the memories of love, sex, and loss which flicker through the later half of the poem. But the shadow on her face is also her face, which is Black and therefore hypervisible in Stony Brook.

Jordan goes on to identify with the blackbirds (“I conspire with blackbirds light enough to fly/

but grounded by the trivia of appetite”), who like her should be able to fly away from this “white place”, but, like her, are trapped there by “the trivia of appetite”—Jordan is in Stony Brook because she is being paid. White people have power and money, and Jordan has to accommodate them if she (like the blackbirds) is going to eat.

Jordan’s disconnection from her lover (65 miles away in New York?) is also a disconnection from Black community engineered by a white hegemony that grounds blackbirds and blasts trees. The hurricane becomes a metaphor for white power and its sterile obliteration of growth and life to make way for its own occupation. (Jordan wrote frequently about native oppression and native genocide.)

Jordan’s erotic memory is both a painful contrast to the alienation of Stony Brook and a comforting possible alternative. “I desist decease delimit: I deny” is an effort to forget a memory that hurts because it is unattainable. It’s also, though, the memory itself, which serves as a refuge and as a refusal to accept the “white place”—which after all, is not entirely or only white as long as Jordan and her memory are there.

The concluding couplet (“For all I can remember all I know/only shadows flourish; shadows grow”) is a wistful, sad recognition that Black community and Black love here, in this “white place” are substanceless; they have no body, only memory, hope, or dream.

But at the same time, those dreams, hopes, and memories are real and growing; they are in Stony Brook too, not least because Stony Brook is, in the poem, subsumed in the poem. Jordan takes Stony Brook into her mouth, and it becomes, thereby, her body and her shadow. The landscape of whiteness is overwritten—at least in a potential dream or future—by Black love, Black community, Black imagination.

Reading the erotic as political, and/or vice versa

Jordan’s longing and her alienation are both erotic and political; she misses her lover as her lover, and she misses her lover as an embodiment of community and belonging not available to her in the white (and heterosexual) rural/suburban 1980s university. Desire shadows politics and politics shadows desire; the meaning of love and sex for a Black queer woman is inseparable from the institutions and power relations which delimit where that love can exist and where it can recognize itself.

The poem gets its power in part because it refuses to recognize those limits. Jordan’s sonnet (that old white form) will not adhere rigidly to politics or to erotics. It shakes them together, cutting one to the shape of the other, like the hurricane snaps off the trees, or conflating one with another, like a (Wallace Stevens?) blackbird swapped with its shadow. If whiteness is in the business of studiously segregating bodies and experiences, then Jordan’s poem is made of irresponsiblities which fly from here to there, present to past. Where dark and light, pain and pleasure, hope and memory meet, shadows flourish.