Jurassic Park Is a Colonial Playground

On lost world imperialism

Jurassic Park turned 30 this week, so I thought I’d share this piece on the franchise and the colonial implications of the dinosaur adventure genre.

____

Where do you go for adventure? The question answers itself: for adventure, you have to go somewhere else, out there, over the horizon. A quest involves travel. To be a hero, you need to leave home to make discoveries; you need to go somewhere else to conquer and kill. For creators in the West, it’s hard to imagine adventure without colonialism.

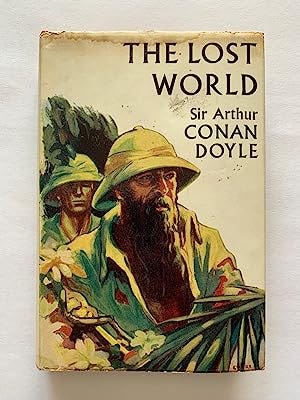

This leaves the contemporary adventure writer with something of a problem. The era of colonial conquest is fading into the past. The world is smaller than it used to be; it’s not so easy to imagine traveling somewhere wild and unmarked, where no one has traveled before. As Arthur Conan Doyle wrote way back in 1912 in his adventure classic The Lost World,

The big blank spaces in the map are all being filled in, and there’s no room for romance anywhere.

Even back then, colonial adventure was starting to be an exercise in nostalgia. Now, a hundred years later, what’s a pulp adventure writer to do?

Conquer the Past

Conan Doyle solved this problem in an ingenious manner. The Lost World locates adventure far away, in that staple of colonial fiction, the Amazonian rain forest. But it also sends its adventurers, led by the irascible scientist Professor Challenger, into the past.

The Lost World is one of the first famous examples of dinosaur fiction. Professor Challenger and his band make their way to a forgotten plateau, where giant saurians roam the earth side-by-side with prehistoric fauna and atavistic ape-men. The map of the world is getting filled in, so Conan Doyle simply imagines himself into a past when there was more room to roam and conquer.

The novel The Lost World isn’t much read in our day, but even so, the world it depicts is not exactly lost. Conan Doyle’s vision of dinosaur adventure lives on, most visibly, in the fantastically successful Jurassic Park films. Like Conan Doyle, the Jurassic Park films are nostalgic for an adventurous past. You can’t go over there, even to the Amazonian rain forest, to find the uncivilized wilderness anymore. Jurassic Park reaches back in time to bring that nostalgic primitive other to your door. Dinosaurs stand in for distant worlds we conquered once, and would like to conquer again, even though we know we really shouldn’t.

Of course, dinosaurs didn’t actually inhabit a Brazilian plateau in 1912; distant lands were not, contra Conan Doyle, atavistic holdovers from a forgotten past. But The Lost World neatly captures an implicit colonial conviction that the farther you traveled from England, the further into the past you went. Nineteenth-century anthropologists believed that people in Africa or the Americas or in Tasmania were “living representatives of the early Stone Age,” as Victorian writer Edward Burnett Tylor put it. To travel across the globe was indeed to travel into the past. You didn’t need a time travel machine to visit prehistory. You just needed to grab a rifle, pack some supplies, and get on a boat. “The way colonialism made space into time gave the globe a geography not just of climates of cultures but of stages of human development that could confront and evaluate one another,” Jonathan Rieder explains in Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction.

In this context, Conan Doyle’s The Lost World wasn’t an innovation so much as a literalization. Europeans in the early 20th century believed that the colonies were prehistoric holdovers. Conan Doyle just populated that prehistoric landscape with stegosaurs and pterodactyls. The explorers even find, inevitably, prehistoric ape-men whom they cheerfully exterminate and enslave. “At last man was to be supreme and the man-beast to find forever his allotted place,” the narrator exults. Humans conquer the past and impose modern order in a genocidal orgy of progress. “The age of romance was not dead,” our hero says with satisfaction.

Domesticate the Colonies

Michael Crichton’s 1990 novel Jurassic Park, and the film series it inspired, are a lot less explicit about the connection between fantasies of living primitives and colonialism. Crichton does not have his adventurers go out to a Brazilian plateau to discover a lost world of dinosaurs. Instead, his great lizards are created by advanced technology. Scientists clone Tyrannosaurus and Velociraptor to serve as theme park attractions. The park founders mean to provide entertainment for kids — until the inevitable disaster.

But while Jurassic Park isn’t as blatant as Conan Doyle, colonial touches still abound. The dinosaur theme park is located in an island off Costa Rica, which means that American visitors are still, like Challenger, traveling to a tropical locale to find their dinosaurs.

Moreover, the films, overseen by Steven Spielberg, include visual references to colonialism. Robert Muldoon (Bob Peck), the big game hunter whose task it is to corral the dinosaurs in the first movie (1993), spends most of his screentime in a rugged cowboy hat, reminiscent of that other great Spielberg colonial adventurer, Indiana Jones. The second film, The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997) opens with a family on vacation on a tropical beach. In Crichton’s version of this scene in the novel, the family is a bunch of modern middle-class Americans. Spielberg, directing, gives the sequence a period twist. The family in the film is wealthy and British, with numerous servants feeding them wine and prawns. The retro imperial self-satisfaction is interrupted, inevitably, by retro monstrosities.

The Jurassic Park films also reference more recent colonial adventures — specifically, Vietnam. Enormous thundering dinosaurs aren’t usually thought of as stealthy adversaries, but the Jurassic Park films have a consistent motif of jungle ambush.

The six-foot tall, pack-hunting Velociraptors are presented (in book and movie series) as intelligent and crafty opponents, who use the Central American landscape to their advantage. Virtually every one of the four films features scenes that could come out of a Vietnam war movie, in which men creeping through the alien jungle are attacked from cover by the primitive natives. In Jurassic World (2015), a genetically engineered dinosaur actually has camouflage abilities; in one scene it emerges from the foliage much like Stallone does in Rambo: First Blood (1982). As in Apocalypse Now (1979), in which Vietnamese fighters improbably use bows and arrows, the colonial past strikes from cover to devour the present.

Cheer for the Saurian Freedom Fighters

The Jurassic Park franchise has a modern-day awareness of the implications of colonialism — and it consistently critiques them. Bringing dinosaurs back to life through genetic engineering is presented as an act of imperial hubris and defilement. The mathematician Ian Malcolm in Crichton’s book argues that scientists always destroy what they explore. “Astronauts leave trash on the moon. … Discovery is always a rape of the natural world. Always,” he declares. In the first film, Jeff Goldblum, playing Malcolm, utters similar lines: “What’s so great about discovery? It’s a violent, penetrative act that scars what it explores. What you call discovery, I call the rape of the natural world.”

Cloning dinosaurs is presented, explicitly, as a destructive act of colonization and “penetration.” Malcolm sees mucking about with the reproductive cycle as an invasion — an analogy all the more uncomfortably judicious because colonial invasion almost always includes widespread sexual violence.

Jurassic World adds another anti-colonial twist; in the film, the U.S. military is trying to use cloning technology to develop dinosaurs who can be used in warfare. “War is struggle. Struggle breeds greatness,” the asshole military man declares, and then goes on to babble about using Velociraptors in Afghanistan and Pakistan to replace drones. In resurrecting Velociraptors and genetic monstrosities, the American government is advancing warfare and invasion overseas—bringing back an era of colonial conquest.

Conan Doyle in The Lost World believes Professor Challenger and his companions have every right to murder the ape-men, overrun the plateau, and name it for its first “discoverer.” In contrast, the Jurassic Park series takes care to punish its colonial fantasists.

John Hammond, the developer of the park, suffers an ignominious death in the novel. In the film (where he is played by Richard Attenborough) he survives, but has to admit that his retro-adventure park was a terrible idea. The military dude who dreams of imperial conquest in Jurassic World also meets an overdetermined but satisfyingly bloody end. “We’re on the same side!” he tells the raptor as it stalks him. Like many colonizers before him, he thinks the natives welcome his schemes and depredations. The raptor disabuses him. Toothily.

The narrative of the Jurassic Park franchise, then, takes a strong stand against militarism, Western hubris, and indiscriminate and exploitive “discovery.” The meta-narrative, though, is a little more complicated.

Colonialism Is Fun For All

The plots of the Jurassic Park series repeatedly show that resurrecting a lost era is wrong and leads to death and tragedy. The popularity of the films themselves, though, show that resurrecting a lost era is really fun and can be enjoyed by the whole family in a movie theater of your choice. The primitive past lives on, in a distant South American island which you can discover and then explore at your leisure.

From this perspective, Jurassic Park is not about the impossibility of taming the wild. Rather, it’s a demonstration of how you can successfully domesticate a slavering and problematic past. After all, even if Jurassic Park III (2001) improbably suggests that Velociraptors have speech, the fact of the matter is that dinosaurs aren’t humans. The nefarious, stealthy, treacherous half-breed in Conan Doyles’ The Lost World is an egregiously racist trope. The half Tyrannosaurus, half Velociraptor in Jurassic World perhaps nods distantly to the same evil mixed-race eugenics fears. But the connection is so attenuated that most of its power to offend is gone.

Similarly, the Velociraptors who sacrifice themselves for humankind in Jurassic World recall Gunga Din and all those indigenous companions in films past who throw their lives away to save the condescending white heroes. The Tyrannosaurus rampaging through the mainland in Jurassic Park III nods to the racist fever dream of King Kong, in which the giant jungle humanoid breaks its chains and destroys the modern cityscape. But replacing humans and apes with dinosaurs leeches out much of the colonial subtext. Jurassic Park takes the ugly past and makes it safe. It sets up a controlled environment where racist tropes and colonial narratives are defanged and domesticated. They can roar and snap at will; no one gets hurt.

The question is, why are we so eager to tame this particular monster, rather than just getting rid of it altogether?

The answer in part is that adventure fiction is so tightly tied to the history of colonialism that it’s difficult to disentangle one from the other. Big game hunters, jungle attacks, exotic locales, and exciting atavistic dangers — they people our fantasies, from The Lost World, to King Kong, to Apocalypse Now, to Indiana Jones, to Tomb Raider, and on and on. New stories are made out of old stories, and the old stories are steeped in colonial fantasy. It’s hard to escape them — and so Jurassic Park doesn’t try. Instead it contains them, and puts them on an island where you can enjoy them in relative safety.

There’s another reason that Jurassic Park resurrects the old bones of colonial adventure, though. Colonial adventure is pleasurable. Just as the sight of real-live dinosaurs has a visceral appeal, so too the tropes of colonialism get cloned so assiduously because people like those tropes. The exciting rush of discovering a primitive land and killing the inhabitants — always in self-defense! — has great appeal. Readers and audiences like to imagine they’ve found a more primitive, more real landscape, on which they can write their names and dreams.

And so the Jurassic Park films show resurrected life breaking free again and again on some distant island. Civilization disintegrates, torn apart by the primitive, in a repeated terrible, exhilarating ritual. The past is a carefully arranged plateau, onto which viewers climb to marvel and exult. It’s romantic. It’s spectacular. It’s fun. Colonialism always is, for the colonizers.