Men in 3 Women

Robert Altman, Shelly Duvall, and Sissy Spacek switch selves.

Shelly Duvall died earlier this month. As a tribute, I thought I’d reprint this piece I wrote for Patreon some time back on what’s often considered her most iconic role.

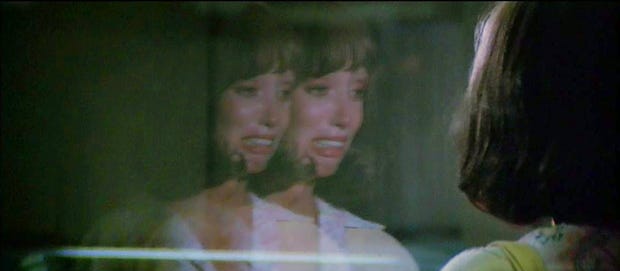

In a thematically iconic images from Robert Altman’s 3 Women (1977), we see Shelly Duvall’s image doubled in a glass partition, her face turned into overlapping faces. The three women of the title are Duvall’s image, Duvall’s image, and Duvall, looking through the glass. The observer is included in the film, a third term who both generates identity and floats outside of it.

The third term is gendered by a kind of extrapolation; we see two women, and so the person creating those two women must themselves be a woman. The director, from this perspective, is a kind of honorary non-man, inhabiting and identifying with his subject and therefore escaping his self. The film plays with the pleasurable sensation of being the other even as it expresses anxiety about the usurpation of male position and male prerogative.

The movie starts as Pinkie Rose (Sissy Spacek) arrives for her new job at a run-down, medically sketchy California spa. Millie Lammoreaux (Duval) is assigned to teach her the routine. Pinkie, who looks like she could be sixteen, instantly develops a (mostly?) platonic crush on Millie. She quickly maneuvers her way into being the other woman’s roommate.

In most descriptions of the film I’ve seen online, Pinkie and Millie are described as opposites; Pinkie is said to be shy and retiring, while Millie is extroverted and confident.

That’s sort of accurate—but then, not really. Pinkie isn’t shy; she’s awkward in social situations, but she also has moments of exuberance and fun, as when she suddenly submerges herself in the pool at the spa, or downs a beer all at one gulp, and then cheerfully burps.

Millie, in contrast, talks all the time. But that’s clearly a way to cover her social awkwardness and nervousness. No one ever listens to her, and the men she obsessively flirts with see her as a ridiculous nuisance. Duvall, through nervous glances and brittle flashes of gloom, shows that Millie is aware that everyone hates her, but tries to conceal it from herself. Her doubt and insecurity causes her to lash out at Pinkie when the latter tries to stop her from sleeping with the married hotel owner and former stuntman Edgar Hart (Robert Fortier.) Millie’s rejection leads Pinkie to throw herself from the balcony, putting her in a coma.

Millie and Pinkie aren’t exactly opposites, then. Rather, they’re both variations on a single, somewhat invidious stereotype—the failed single woman, whose search for affection leads to self-parody and self-harm.

Edgar is a (gross, sad) object of desire. He’s also a catalyst. Pinkie’s coma leads her and Millie’s relationship to change radically. Millie, while Pinkie is unconscious, becomes solicitous and focused on her welfare. Pinkie, when she wakes up, takes to smoking, drinking, and flirting. With a slight wardrobe change and a major alteration in attitude and swagger, Spacek magically makes the character age 10 years.

The general reading of this transformation is that the characters are becoming each other. That’s a reasonable interpretation; Altman fills the movie with references to doubling and mirror images. There are a pair of twins who work at the spa with Millie and Pinkie, and Pinkie muses about what it would be like to be a twin, and perhaps lose track of which of you was which. Pinkie and Millie also share the same given name (Mildred) and they’re both from Texas. They are, Altman keeps suggesting, the same person. So when their personalities transform, it makes sense to think that they are simply swapping selves—especially when Pinkie demands that Millie start calling her “Mildred.”

Swapping selves is not exactly what happens though. The new Millie doesn’t have Pinkie’s playfulness, and she’s not childlike. Instead, she turns into a mother figure, urging Pinkie to go to bed early per doctor’s orders, trying to coax her to remember her past, which has been partially erased via amnesia, and chastising her for taking the car without asking. For her part, Pinkie becomes the popular, easily sexual young single swinger that Millie notably failed to be. She hangs out on the patio with all the guys who laughed at Millie, and even has a fling with Edgar.

Pinkie and Millie, or Mildred and Mildred, are cycling through different potential female roles: frustrated spinster, innocent child, caregiver, temptress. They’re not switching psyches—which raises the question of in whose psyche, exactly, these identities exist. Who is trying out different female identities? Whose reflection is doubled in the glass?

One plausible answer is Altman himself, who is after all asking these actors to play people other than themselves. Another possibility is the (male or female?) viewer. The way Pinkie and Millie (or Mildred and Mildred) try to become each other and keep missing could be analogized to the always failed identification of viewer with screen image, the Lacanian recognition of a self created by that moment of recognition. Pinkie, waking form a coma, sees her parents—but insists they aren’t her parents. Which of course they aren’t; she’s an actor, and the parents are also actors. The selves on screen are not real selves, as perhaps the selves offscreen aren’t either. There is no third woman. Or, by the same logic, the third woman is everyone.

The loosening of the bonds of identity can be liberating. One of the pleasures of film is that you can identify with and turn yourself into other people, not least other genders. But having no core self also puts you at the mercy of other’s (gendered) vision of you. Edgar, for example, projects his own desire onto the Mildreds, and his own identity onto them when he finds them sleeping together in their apartment (as the landlord he has a key.) Pinkie came to sleep with Millie after a bad dream, but Edgar leaps straight to porn, and suggests that the women have been learning “new tricks.”

Edgar imagines Pinkie and Millie desire each other as he desires both of them; he is fantasizing himself as them. Altman’s position is not entirely dissimilar, as he puts his words, desires, and dreams (the film is based on a dream) into his female characters. It’s Altman staring through/with Pinkie’s eyes when she gazes rapturously at Millie. It’s, at least to some degree, Altman who wants to be who she’s gazing at, and perhaps wants to be with who she’s gazing at. The (partial, mistaken) exchange of identities between Mildred and Mildred is a metaphor, or a reflection, of the partial, mistaken exchange of identities between Altman and Mildred.

The movie is, then, at least obliquely, raising queer possibilities of same sex love and cross-gender identification. That’s where a lot of the film’s energy and joy come from. It’s also where a lot of its anxiety rests.

Edgar, drunk, after barging into the women’s apartment in the middle of the night, finally gets around to telling them that his pregnant wife Willie (Janice Rule) is in the process of having a baby. Willie is a silent figure through the bulk of the movie, who paints vivid, agonized, sexual murals at the bottom of pools. She’s an analog in some ways for that other weird unspeaking creator of dreams, Altman himself

Millie and Pinkie rush to her room to help Willie deliver; Millie then stays to help and directs Pinkie to drive to the hospital to get a doctor. But Pinkie is frozen, watching, unable to move (not unlike the movie viewer) while the male baby is born dead. Female/female bonds, women positioning themselves as creators (since Willie is an artist), and/or men positioning themselves as women (since Altman is Willie) all lead to sterility. The play of fake selves in this particular narrative can create only more contingent, fake selves, not new life.

After the stillbirth, the movie jumps ahead some weeks, where we find everyone has changed identities again. Edgar is, apparently dead in a firearm accident—it’s suggested the women may have killed him. Meanwhile, Pinkie has regressed into adolescence; she calls Millie “mother” and defers to her more consistently and thoroughly than at any point previous. Willie has become a more open, grandmotherly figure. Millie is stern, upright, self-contained, and confident.

The ”happy ending” here is predicated on the removal of men from the equation altogether; philandering, bad patriarch Edgar has been usurped. But the patriarchy has been replaced not with an alternate, communal structure, but with a parodic traditional nuclear family. The flesh and blood man is gone, but men remain as a ghost or a presence—the structure around which the three women live.

I wouldn’t say 3 Women is exactly misogynist or homophobic. I wouldn’t say it isn’t exactly, either. The film is about not allowing itself to be pinned down to any one perspective—or to any three perspectives, or to any two genders. Altman is the third woman in the same sense that Pinkie is Millie, or that Millie is her mother. Which is to say, they are themselves as much as anyone can be any self in a movie, a dream, or a mirror.