No Happy Ending: Steven Universe as Bleak Parable

Steven Universe: The Movie revisits and rethinks the hopeful series.

When a completed, beloved television series spins off a film, the result is going to be, one way or another, an exercise in nostalgia. At worst, you get Star Trek: The Motion Picture, where the bulk of the movie is characters staring mournfully into the distance to remind you that you too, are supposed to be suffused with sentiment. More successfully, as in Deadwood, the nostalgia can be thematized, or used to advance the show’s concerns—in Deadwood’s case the ambivalent celebration of the American West and the building of community and nation.

Rebecca Sugar’s Steven Universe: The Movie (2019) goes even Deadwood one better. The film at first appears to be a sweet, simple coda to the series, recapitulating themes and plots for one last victory lap around the cosmos. But by the end, it feels less like a celebration than like a tearing open of a wound. To revisit Steven Universe is to acknowledge that Steven Universe is less a beloved friend than a pink ball of trauma. Nostalgia is not a warm, fuzzy glow, but a bleak reminder that memory can be torture as well as balm.

Back to the Universe Beginning

The film starts a couple of years after the end of the tv series. Steven is now 16, and enjoying his happily ever after. He and his space gem friends—Garnet, Amethyst, and Pearl—won their 6000 year war with the imperial fascist dynasty of the Diamonds by converting Yellow Diamond, Blue Diamond, and the ruling White Diamond to good (though Steven still has to remind White that the “lesser entitites” aren’t actually lesser. “Equal entities,” she sighs, like an exasperated student reiterating a lesson.) The many gems wounded and corrupted in the conflict are healing, and Steven has nothing to do but sing songs with his friends about how life is perfect and will remain so forever.

Of course, if that were the case, there wouldn’t be much in the way of a movie. And sure enough, things deteriorate quickly. Spinel, a rubbery, stretching pink weirdo with an upside-down heart gem, lands on earth and starts injecting poison into the planet’s core. She wields a scythe that resets Garnet, Amethyst and Pearl so they don’t remember anything that’s happened in the last 6000 years, and that robs Steven of all the powers he gained over the course of the television series.

The narrative ploy here is clever; by erasing memories and powers, Spinel essentially resets the story. Character development and plot both rewind. The movie can be the same as the show, because the movie has wiped the show clean. Fans of the series presumably tuned in to see more of the series, and this way they can—Ruby and Sapphire rediscover their love for each other and fuse into Garnet; Pearl learns to overcome her blind loyalty to one person and set her own goals and desires; Steven masters his powers. If you tuned in for Steven Universe, you get exactly what you were expecting, again.

Repetition is fun; it’s what we want from pop culture. But repetition isn’t just fun. It can also be an ominous indication of stasis, or of an inability to grow. Rebecca Sugar is well aware of that—and she signals as much by slipping a terrifying parable into the middle of her sweet tale of love and revisiting friends.

Watch the Same Show Forever

Spinel also has her memory erased by the scythe. But eventually, she gets it back, and tells Steven her origin story. She was originally the robot toy/plaything of Pink Diamond, Steven’s mother. Pink Diamond would play with Spinel in her garden for hours. But eventually Pink was gifted a world of her own to conquer/rule—the Earth.

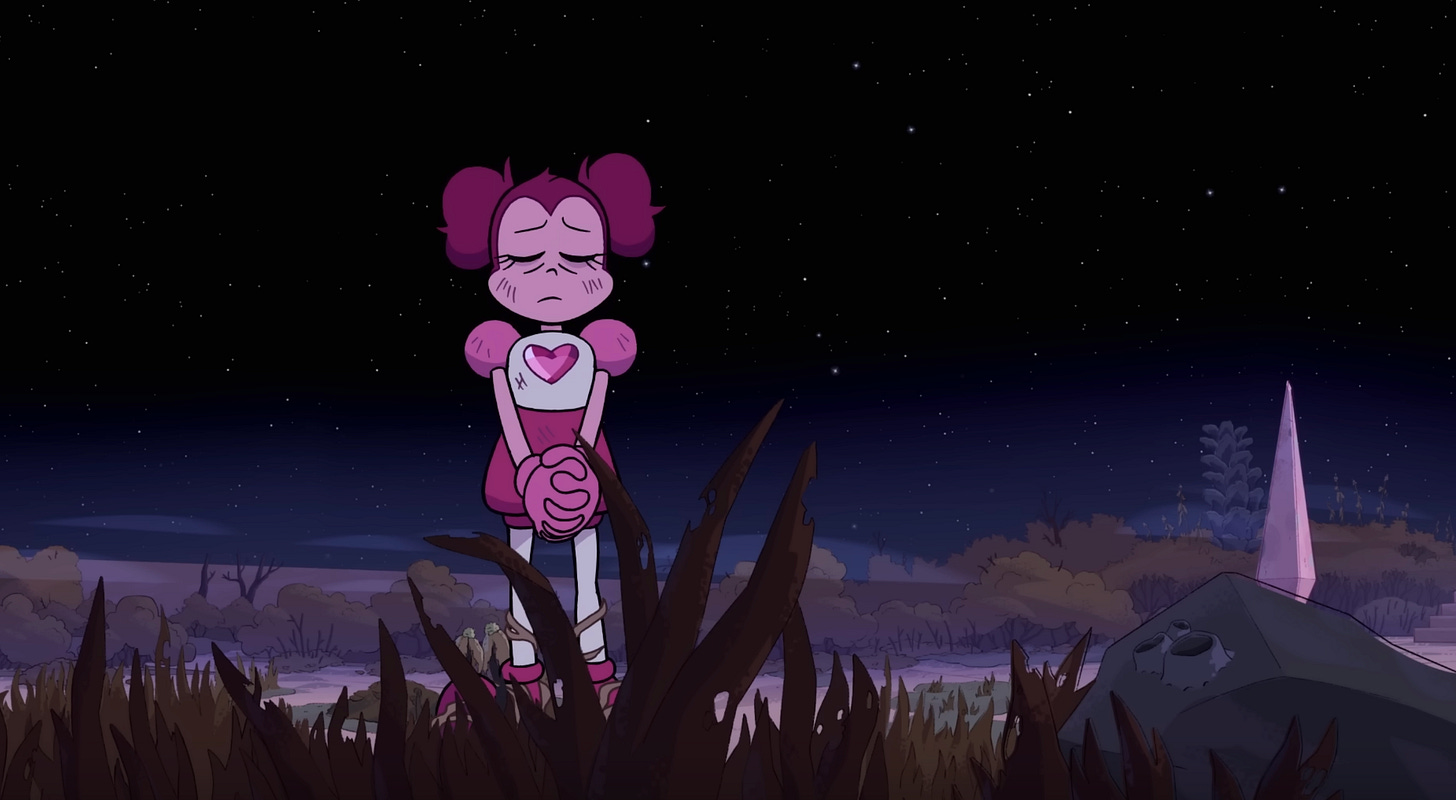

Pink was enthralled with her new toy, and bored with Spinel. So she told Spinel they were playing a game; Spinel should stand still in one place, and Pink would come back for her. Spinel stood in the garden for 6000 years, waiting. She only gave up on Pink’s return when she saw a video message from Steven, explaining that he was Pink’s child. Spinel wants to destroy him and his planet out of revenge.

In the television series, we learn eventually that Steven’s mother could be deceitful and selfish. Most of her evil actions, though, were in the interest of saving Earth from destruction by the diamonds. The treatment of Spinel, in contrast, is completely thoughtless and nakedly cruel.

Pink doted on Steven as a mother. But she neglects Spinel. And that neglect resonates paintfully, and frighteningly with the show’s queer themes. Sugar was rightly praised for including lesbian relationships in her cartoon, and for presenting queer love as joyous, nurturing and powerful, despite a lot of pushback from Cartoon Network. The rigid, intolerant Diamonds, with their eugenic conviction that everyone must fill the place they were born for, are obvious metaphors for intolerant, homophobic parents. The series is about queer children learning to love themselves despite parental disapprobation—and about, eventually, winning those parents over, and showing them how to love their queer kids.

Spinel’s torture, though, is difficult to reconcile with reconciliation or healing. For her, parental cruelty and rejection feels like 6000 years of self-loathing, unrequited hope, and misery. The garden around her withers; her heart curdles and turns upside down. It’s emotionally devastating, and easily the most vivid and memorable part of the movie, if not of the series. The inevitable healing feels shallow and unreal in comparison. At the center of this film about friendly, familiar reiteration is a brutal, inescapable reiteration of trauma and loss. Nostalgia—the revisiting of beloved memory—is swamped by the frozen inescapability of memories which aren’t beloved at all.

More, in the context of Spinel’s ordeal, the very nostalgic impulse to return to the series takes on ugly implications. Are we enjoyably retelling a story we all love? Or are we returning to a knot of anguish and misery which we must ritually but futilely pretend to undo again and again, only to watch it endlessly reform?

Happy for now. Or not.

The ostensible lesson of the movie, is that, per Steven “There’s no such thing as happily ever after.” Steven interprets that to mean that there is no permanent resolution; life goes on, and you need to continue learning and changing.

But Spinel’s story suggests a less cheerful possibility. Maybe there’s no such thing as happily ever after because some trauma, some neglect, some violence, simply can’t be healed or forgotten. Steven and the gems defeated their demons and overcame homophobic parental abuse—and then they forget their triumphs and their joy and the friendships they’ve built, and have to do it all again. Their very love is a glue trap, holding them in place. To heal is just to set your heart up so it can be turned upside down again—not by the next thing, but by the memories you can’t escape.

I still haven’t seen Steven Universe Future, the epilogue series that (I understand) explores some of these issues in further depth. But Steven Universe: The Movie already, asks viewers to revisit the original not just to re-enjoy, but to re-see.

Steven Universe is sometimes criticized for being too twee, or for offering its fascist villains a too easy road to redemption. Those concerns aren’t necessarily wrong. But Steven Universe: The Movie suggests they are concerns that Sugar has thought of, and to some extent shares. It’s worth remembering, again, that Cartoon Network was very opposed to Sugar’s efforts to include queer stories in Steven Universe. They told her she couldn’t talk about the queer aspects of the show in public, an ultimatum which Sugar has said was extremely upsetting and harmed her mental health.

They basically brought me in and said, ‘We want to support that you’re doing this but you have to understand that internationally if you speak about this publicly, the show will be pulled from a lot of countries and that may mean the end of the show.’ They actually gave me the choice to speak about it or not, to tell the truth about it or not, around 2015/ 2016, by then I was honestly really mentally ill and I dissociated at Comic Con. I would privately do drawings of these characters kissing and hugging that I was not allowed to share. I couldn’t reconcile how simple this felt to me and how impossible it was to do, so I talked about it.”

Sugar and Spinel

Sugar was crafting a narrative of healing and acceptance. But that narrative became itself, in the hands of her corporate Diamond overlords, an instrument of repression, guilt, and cruelty. Steven Universe isn’t Sugar comfortably hanging out on a utopian earth asserting, “Hey, look, love wins easily and everything’s okay!” It’s Sugar standing in that garden, watching the flowers die, telling herself love is going to win out because the alternative is too terrible to contemplate.

I wouldn’t argue that Steven Universe, series or movie, is really about depression and despair, rather than about hope and healing. Instead, I’d say that Steven Universe: The Movie, in looping back on its own happy ending, suggests that happy endings, especially when reiterated, contain within themselves a recognition of more painful possibilities.

In the movie, Rebecca Sugar lets you know that the entire time Steven was turning his fingers into tiny cats, or teaching Peridot to care for her friends, or converting White Diamond to the good, Spinel was out there in space, heartbroken and suffering. You could say that Steven Universe is what Sugar made so she wouldn’t have to look at Spinel. Or you could say that Steven Universe is what Sugar made because she never stopped looking.

I still need to watch Steven Universe but I've heard great things. Thank you for this excellent pop culture analysis.

I don't want to make this about me, but learning about Sugar's oppression makes me think about how people's lives (including mine) get redacted for the convenience of the system.

I'm not queer and had little interest in the show, in spite of reading good reactions online. (Five seasons of anything consumes a lot of time and mental energy, even if the installments are short. )

This news of Sugar's oppression, however, makes my head throb. I have bipolar disorder (and show characteristics of autism, though not formally diagnosed). For much of my life, the message from the system has been "You know how you are? Please don't be that way" because "that way" inconveniences others.

To be told to deny the point of something she created, into which she'd put her identity, because it would cost someone a slice of their profits or make them acknowledge an uncomfortable truth? No wonder she broke for a while. How, in the 21st century, can powerful people justify forcing us into standardized boxes? If Greg Abbott can use a wheelchair and still sell his "Boss Sunglasses from 'Cool Hand Luke'" image to the public, why is another type of difference so marginalized?