Past Lives Is An All-Time Great Romcom By Not Being a Romcom

Fall in love with melancholy

In the US, romances, both novels and films, have to have a Happily Ever After (HEA), or at least a happy for now. The genre requires that the two main characters end up together and that the conclusion leaves you with a feeling of uplift and empowerment. Everyone gets what they want, both in career and in love—obstacles exist to be overcome in the rush of joy. If you want something more melancholy, you head for lit fic.

You could argue that Celine Song’s melancholy, elegant indie film Past Lives is a kind of filmic lit fic, I suppose. But its plot is straightforward, and its characters are transparently, satisfyingly lovable; it’s got the emotional beats and satisfactions of genre romance, but without the happy ending. And it’s glorious.

The film starts in South Korea; 12-year-old Na Young (Seung Ah Moon) and her classmate Hae Sung (Seung Man Yim) compete for first honors in their class. They also have crushes on each other, so their parents arrange a date at the park. Shortly thereafter Na Young and her family immigrate to Canada. Twelve years later, Na, now Nora (Greta Lee) is trying to make it as a writer in New York, when Hae Sung (Teo Yoo) contacts her via internet. The two start a long distance relationship, but can’t coordinate to meet in person, so Nora breaks it off. She meets another (white, Jewish, short) writer, Arthur (John Magaro), and they marry. Twelve years after that, Hae Sung visits New York City to see Nora. They spend a few days together and talk about what might have been. Then Hae Sung leaves.

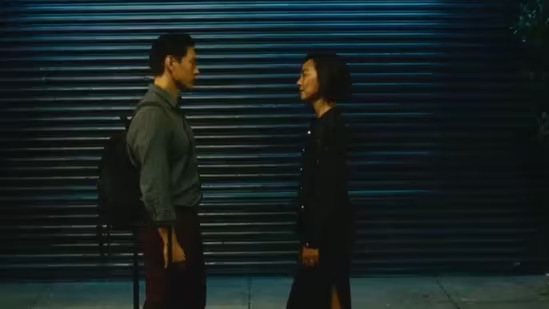

In short, nothing happens; the romance doesn’t ro. But Song and her stunning cast orchestrate the nothing happening with such grace it will break your heart. Little moments echo and resonate across time; when Nora and Hae Sung meet for the first time in 24 years, glancing nervously at each other, the movie cuts back for a beat to the two of them playing on a climbing wall of blocks as children on their one date, looking at each other and giggling. Nora cries as a child when Hae Sung beats her in the class rankings for his first and only time, and he walks away from her dejected but indulgent. Years later she tells him she doesn’t cry anymore, but the one exception is when he leaves New York, and she weeps helplessly in her husband’s arms.

These callbacks wouldn’t resonate if you didn’t fall for the characters. Romcom characterization can be broad to the point of caricature, but Song takes a more subtle approach. One of my favorite moments is just after 24-year-old Hae Sung receives his first text from Nora. He’s in bed after a night of drinking, gets dressed, and eats with his parents, preparing for school. He seems low key and hung over, nothing special—but his mother asks him, “Why are you in such a good mood?” He pauses, and we cut to a scene of Nora running across the street to get to her laptop so they can have their first live video conversation. It’s such a quietly joyful, funny, exuberant scene; there aren’t many movies that capture young love with such low-key perfection.

If you don’t want Nora and Hae Sung to get together by the end of the film your heart is a big old hunk of rock. But Nora’s husband isn’t the bad guy. On the contrary, he’s sweet and patient, mastering his jealousy for the sake of his wife, who he feels he doesn’t quite deserve. He worries she’s just with him by chance, and that there are parts of her he’ll never know. He admits to her that he is trying to learn Korean because that’s the language she speaks when she talks in her sleep; he wants to be able to understand her dreams.

Those dreams are big; Nora wants to win a Nobel Prize she says (as a child); then a Pulitzer (as a young woman), and finally, at 36, she wants a Tony. As Nora, Grace Lee’s face is delightfully animated—determined, flirtatious, certain of what she wants, except in those moments when she isn’t. Teo Yoo as Hae Sung in contrast is stolid, and, as he says, “normal,” so his brave declarations of emotional depth (“I didn’t know it would hurt to like your husband this much”) land like a sucker punch. (Seriously, I just teared up writing that line down.)

The title, Past Lives, refers to a Korean folk belief that people who are close to each other in this life met in a past life and were important to each other. Nora “seduces” Arthur by telling him that she doesn’t believe the story and just is telling him about it to seduce him, so it’s not exactly meant to be true. But it serves as a metaphor for the way that Nora and Hae Sung’s past and future lives, both actual and possible, wrap around each other, tying them to each other with memory, with meaning, with love and hope.

The genius of Past Lives is that, while it’s not exactly a romcom, it’s shadowed by the romcom it isn’t, which hovers off to the side, just offscreen, where Nora and Hae Sung keep looking awkwardly to avoid looking at each other. The sad ending here is only sad because you can see the happy ending. What might have been, and what might be, are what gives the film its freight of loss. And by the same token, the shadow Nora, who stayed in Korea, makes the real cosmopolitan Nora, pursuing her dream, glow brighter—so brightly that Hae Sung isn’t even willing to say he’d rather she were someone else to him, or to anyone.

Happy endings in standard romances are happy in part because of barriers overcome and wrong paths avoided. The bitter here, by the same token, heightens the sweetness. The past, gone now, makes the present what it is and what it is not, like two languages, heard and half understood in dreams.

A beautiful review. I adored this film for everything it wasn't.

Fantastic review