People Think Kamala Harris Is Inauthentic For the Same Reason They Thought Disco Was Inauthentic

It’s racism and sexism.

Former Obama advisor David Axelrod said in an interview this week that Kamala Harris has a problem with “authenticity.” A number of people on twitter pointed out that Axelrod’s comments were sexist. Then a bunch of other people said, “Hey, what’s sexist about saying Harris is inauthentic?”

So, I’m going to take that last question in good faith. To answer it, it’s useful to talk for a second about rock music.

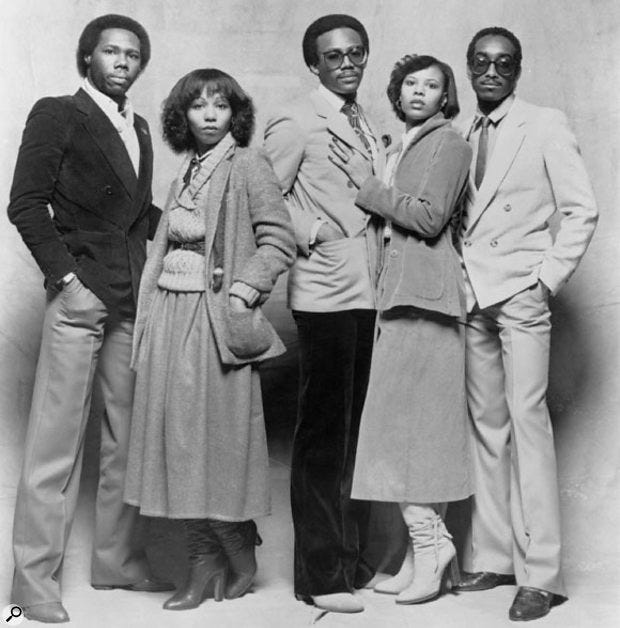

Into the 80s and 90s, rock critics were obsessed with authenticity. The Beatles, the Stones, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and then, hallelujah, Nirvana—these were tough bands whose shaggy hair and obsession with grungy blues showed that they were keeping it real and tough and shaggy and grungy. In contrast, performers like Donna Summer, Whitney Houston, and Destiny’s Child obviously showered, wore make-up, and spent a lot of money on their wardrobe. They were decked out in shallow artifice; they didn’t mean it, the way rock should.

In a seminal article in the New York Times, Kalefah Sanneh pointed out that this formulation was (a) ridiculous, and (b) bigoted.

Rockism isn't unrelated to older, more familiar prejudices -- that's part of why it's so powerful, and so worth arguing about. The pop star, the disco diva, the lip-syncher, the "awesomely bad" hit maker: could it really be a coincidence that rockist complaints often pit straight white men against the rest of the world? Like the anti-disco backlash of 25 years ago, the current rockist consensus seems to reflect not just an idea of how music should be made but also an idea about who should be making it.

Sanneh added that “just as the anti-disco partisans of a quarter-century ago railed against a bewildering new pop order (partly because disco was so closely associated with black culture and gay culture), current critics rail against a world hopelessly corrupted by hip-hop excess.”

The anti-disco fervor he’s referring to was, most notably, a reactionary rally in Chicago’s Comiskey park in which promoters blew up a stack of disco records and fans surged onto the field, ending the game. Rolling Stone critic Dave Marsh noted at the time “white males, eighteen to thirty-four are the most likely to see disco as the product of homosexuals, blacks, and Latins, and therefore they're the most likely to respond to appeals to wipe out such threats to their security. It goes almost without saying that such appeals are racist and sexist, but broadcasting has never been an especially civil-libertarian medium.”

Rock was originally an integrated art form, and its most important early progenitors—Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Little Richard, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke—were mostly Black performers. But in the 60s it became considered white music, and Black performers were relegated to influences. Disco was therefore seen as a threat.

More, Black performers who played the music they had created were also thereafter labeled as inauthentic.

The dynamics here are perhaps most visible in the reaction to Jimi Hendrix when he came on the scene a decade or so before disco. Now, of course, we view Hendrix as the quintessential rock guitarist. But at the time, as Jack Hamilton details in Just Around Midnight: Rock and the Racial Imagination, Hendrix was seen by white rock critics as a sell out and a fraud.

Robert Christgau, the self-styled “Dean of American Rock Critics,” called Hendrix a “psychedelic Uncle Tom,” and approvingly quoted another critic who referred to Hendrix’s “beautiful spade routine.” He sneered at Hendrix for his sexual performance, and really just for performing. When Hendrix played for an audience by playing up his sexuality, he was inauthentic. When Elvis, or Mick Jagger did the same? Well, they were real rock n’ roll.

Hendrix, again, did eventually get into the authentic rock canon. Black women performers, though, had an even tougher time. Christgau was sneering at Nina Simone for being a poseur as late as 1978; he felt if she was real she should have been willing to use gendered slurs in her songs. (She skipped the word “bitch” in “Rich Girl.”)

The Beatles covered the Shirelles “Boys” and pretended to be girls singing about guys. But somehow they were more authentic than the original girl groups, who were mostly written out of rock history. In doing so, critics paved the way for the anti-disco backlash, since disco looks a lot less discontinuous with rock if you acknowledge that vocalist focused, producer heavy Diana Ross Motown sides were always an important part of the tradition.

So! Back to politics.

The discussion of rockism is useful for politics for a couple of reasons. First, it underlines the racial and gender politics of authenticity. And second, it makes it clear that authenticity is comparative. You aren’t just saying someone is not authentic; you’re saying they’re less authentic than this true thing over here.

The backlash against disco was anger because disco wasn’t authentic rock. That is, rock fans wer angry that their genre was being usurped. Disco was fake because it wasn’t the kind of music they wanted, and because it wasn’t being performed by the kind of people they considered the main protagonists of popular music.

More, when people like Hendrix or Diana Ross did play in the genre, they were still considered fake. It’s a double bind; if you’re not a white man and play rock, you’re not playing your music, and are inauthentic (again, even though rock was Black music to begin with.) On the other hand, if you play a different kind of music, and are successful, you’re infringing on real music with your inauthentic bilge.

You can see the problem for, say, Kamala Harris. Harris, as a Black woman, doesn’t look like past presidents, all of whom have been male, and all but one of whom have been white. So how can she be “authentic”? If she behaves very differently from past presidents—if she dresses flamboyantly for instance—she’ll be accused of being inauthentic, because she’s not inhabiting the role of serious politician the way she should (see the outraged commentary on Kyrsten Sinema’s wardrobe, which is the one thing about her that is not in fact objectionable.) If instead she behaves pretty much like any other politician, she’s considered inauthentic because…well, real presidential politicians are white guys, and she isn’t.

Does that mean you can’t criticize Kamala Harris? Of course not. There are plenty of legitimate reasons to dislike Harris’ substantive policies (as there are plenty of reasons to dislike Biden’s.) Similarly, there’s no rule that says you have to love Whitney Houston’s recorded output (I’m not a huge fan.)

The problem comes in when you start moving away from particular specific political critiques (or from personal taste in music) and start making sweeping statements about which human being is real. Because the thing about authenticity is that it isn’t authentic. It’s a subjective feeling. And what that feeling mostly says is, “This person looks out of place in this position of power and/or celebrity.”

In a racist, sexist society, intuitions about who deserves status are influenced by racist and sexist (and homophobic) hierarchies. The better music critics figured that out 20 years ago. It’s time political punditry caught up.