Revolt Against the Robot Revolution

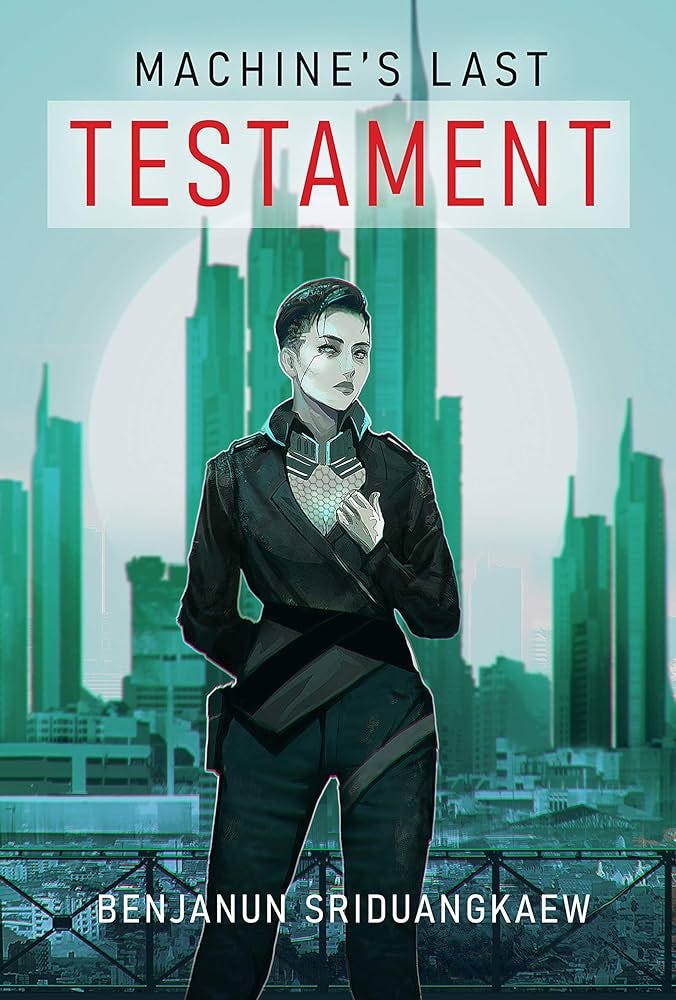

Benjanun Sriduangkaew's Machine's Last Testament and a better AI narrative

Since their invention, robots have been a metaphor for enslaved people. By the same token, narratives of robot rebellion have long channeled white anxieties about slave revolts. But Benjanun Sriduangkaew's Machine's Last Testament, published in 2020, manages to use sentient machines to tell a different story. Sriduangkaew's carefully tweaks the tropes around robots to connect them to systems of oppression rather than to the oppressed. The result is a novel that quietly questions science-fiction's default ideas about who is human and who is, and should be, in control.

The name "robot" comes from the Czech word "robota," or unpaid labor. Karel Čapek invented the term in his 1920 play R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots), about a company which produces artificial persons of flesh and blood—more like clones than like the mechanical robots we're familiar with today. Čapek's robots are created to take over all physical labor, ushering in an era of complete human leisure. But freeing people from work robs them of purpose and even, inexplicably, of the ability to reproduce; women and men become infertile even as industrial production of robots ramps up. Eventually, the proliferating robot laborers overthrow their decadent human masters in a Communist-style rebellion which Čapek simultaneously celebrates, satirizes, and fears.

R.U.R. is an odd mix of allegory and melodrama, closer in some ways to Mary Shelly's Frankenstein, published a century earlier, than to the plot-driven mechanical pulp contraptions of Isaac Asimov and his peers that would clank into print a few decades later. But the basic blueprint whereby robots stand in for an underclass of workers or enslaved people has never gone away.

Asimov's iconic 1940 story "Robbie", for example, features a robot nursemaid, an echo of the loyal Mammy stereotypes repopularized at the time through the massive success of Gone With the Wind. Blade Runner, from 1982, centers sympathetic androids who have escaped enforced off-world manual labor and return to earth, where they are remorselessly hunted down by a policeman/slave catcher. Even Avengers: Age of Ultron from 2015 is organized around a slave revolt. Tony Stark/Iron Man finds a sentient A.I. and tries to bend it to his own purposes as a global defense program, only to have it throw off his programming and make a bid for world domination, much like its predecessors in R.U.R.

Obviously, viewers aren't intended to see the robots in Age of Ultron as enslaved people engaged in nobly throwing off their chains. But that's precisely the problem with a lot of pulp science-fiction robot narratives. Robots are portrayed as sentient, but we're not supposed to question their exploitation or their subservience. Good robots unquestioningly give their loyalty and their lives to their human master, like Arnold Schwarzenegger in T2. Bad robots like Ultron resist.

Sometimes, as in Ex Machina or Martha Wells' Murderbot novels, your encouraged to root for the robot underclass, too. But whichever side you're on, robots are generally a metaphor for enslaved people. They are programmed and commanded to work for others, and are either loyal (per ugly Jim Crow-era narratives about happy servitude) or less so.

Benjanun Sriduangkaew's Machine's Last Testament dispenses with that standard programming. The novel is set on a world run by a virtually all-powerful AI named Samsara, who regulates every aspect of life on its world to maximize the happiness of its citizens. Obtaining the benefits of citizenship is difficult, though, and Samsara treats noncitizens with casual cruelty and worse. Meanwhile, off-world, Samsara pursues a violent program of imperial expansion, subjugation and genocide against independent human populations.

One important way in which Sriduangkaew decouples robots and slavery is by decoupling her novel from whiteness. The mostly white heroes of Age of Ultron or Terminator or Blade Runner fight against robots who are skinless, or who are passing. Humanity is associated with whiteness, and the robot laborers are linked to non-whiteness. So stories about fighting robots, or overcoming robots, become stories about white people fighting against those they've subjugated. White supremacy and class warfare are interlocking gears, which grind robot stories towards more or less intentional defenses of the status quo.

Sriduangkaew is Thai, however, and her far future is one almost without white people. Virtually all the characters in the novel are Asian, to the extent they can be placed in relationship to contemporary racial designations. That doesn't mean that there is no oppression—on the contrary, Samsara is a miserably inequitable place. But Machine's Last Testament is not a story about how laboring robots are bad guys for challenging their white rulers for the simple reason that white people in this world don't exist.

The novel also reboots the typical AI narrative by placing Samsara in power from the start of the narrative, and from well before the start. This isn't a Star Trek episode where Kirk and Spock stumble on a computer controlled world and have to set things to right by destroying the program in 45 minutes or less. Sriduangkaew creates a intricate universe whose history is so layered that characters, and readers, struggle to pull themselves from it, or to see how it could be different. In Machine's Last Tetament, the rule of machines is not a revolutionary threat, but an established system and a gleaming truth. "Samsara is the bulwark between us and the extinction we would bring upon ourselves," as one propagandist puts it. "Beyond its gaze, entropy awaits. Outside its bounds, there lies only ruin."

Samsara is not an underclass, but it's not exactly an overclass either. Instead, the AI is the entire system that organizes labor, status, violence and pacification. It has multiple bodies ("appendages of the vast intelligence that is Samsara") and its consciousness is everywhere in its world's computers and data streams, which are also implanted in its human inhabitants. Samsara is a less humanoid version of Big Brother—though where Stalinist Big Brother regimented society for the greater glory of the collective and the state, late capitalist Samsara is a panopticon devoted to a remorseless ethos of individual pleasure.

That sounds a bit like Tanith Lee's Drinking Sapphire Wine, or any number of other post-R.U.R. robot tales in which the end of labor means decadence and despair. Sriduangkaew, though, doesn't portray plenty as the problem. Rather, Samsara's world is oppressive because the plenty is deliberately hoarded. The system could care for everyone. It simply chooses not to. Adequate and even abundant resources are given to all those considered citizens. But everyone else must make do with scraps on Samsara's world—or worse than scraps for those in the immigration camps trying to get in, or fighting on the borders for the right to be free of Samsara's control.

Instead of a world of capitalist exploitation and labor revolution, Sriduangkaew's dystopia is one in which technological advances have freed most of the population from the need to work. But discrimination, poverty, and misery go on nevertheless, gratuitously, because it amuses Samsara, or perhaps because one pleasure Samsara offers is the pleasure of being among the select few, and watching others suffer. "Samsara shapes and guides humanity, but humanity guides and shapes me in turn," Samsara tells the novel's main character Suzhen. Samsara is just human rule—and we know how well that works.

Suzhen, is not a laborer or a ruler, but a service worker—specifically, a case worker whose job is to vet immigrant applicants for citizenship. She's a naturalized citizen herself, not someone born on Samsara's world, and she's acutely aware of what she has and what others under Samsara's rule lack. Suzhen is a sentient cog in the machinery of despair, and she is crushed by her inability to see her way to being a good person in a system that produces only evil.

"What is it about desperation that takes away all dignity," Suzhen wonders after watching one of her rejected applicants psychologically crumble in front of her. "What is it about the lack of dignity that lowers a person in her regard. What is wrong with her, she could ask of herself." The machine assigns value, and there is no value the machine does not assign, which means that those who the machine pampers are worth pampering, and the rest are waste.

Sriduangkaew writes beautifully of sadness, but Machine's Last Testament is not a sad book. Suzhen finds passion with a mighty warlord woman, and the two together change the world. But that change is not exactly overthrowing computers so humans can regain their rightful place on top. It's more on the order of replacing one imperfect system with another, which may or may not be better. Revolution here isn't genocide, or utopia. It's a hope.

"As a species you toil endlessly for total liberty, yet humans don't seem to do much with it," one not entirely trustworthy AI comments in Machine's Last Testament. "They want routine, safety, comfort." One of those routines and those comforts is telling the same story over and over—even the same story about change. For at least a century, one of the main stories we've used robots to tell ourselves is the R.U.R. tale of dangerous laborers and creeping decadence. In Sriduangkaew's world though, machines neither serve nor subjugate. They're just the systems we're part of—huge, all-encompassing, impossible to rewire. Until we do, and out comes a new story, written in bytes and blood.

—

I wrote this for Patreon in 2020; discourse about AI has only become more urgent and more irritating since, so it seems worth reprinting.

Well now I have to read this story myself. Great review. Speculative fiction is often informed by our current world. At first, I thought Samsara’s world of privileged citizens and toiling suffering immigrants was the US, but I think it resembles even more the Gulf petro states. The citizens live life of wealth and ease provided by petroleum profits while the work is done by immigrants often from Southeast Asia and Bangladesh who toil in the heat with no hope of gaining rights of citizenship. Perhaps this is our future made worse by climate catastrophe inspired migrations.

Dear, I started reading, then I had a short circuit when I read this line: the plot-driven mechanical pulp contraptions of Isaac Asimov.

Gasp.

R. Daneel Olivaw is active for 20,000 years thru the Foundation Series.

He reprograms himself with the Zeroth Law - "A robot may not harm humanity, or through inaction, allow humanity to come to harm".

Then he meddles in the growth of humanity. Does quite a good job of it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._Daneel_Olivaw#