Saving Jews for Fun and Profit

*For Such a Time*, *Schindler’s List* and other gentile savior bullshit.

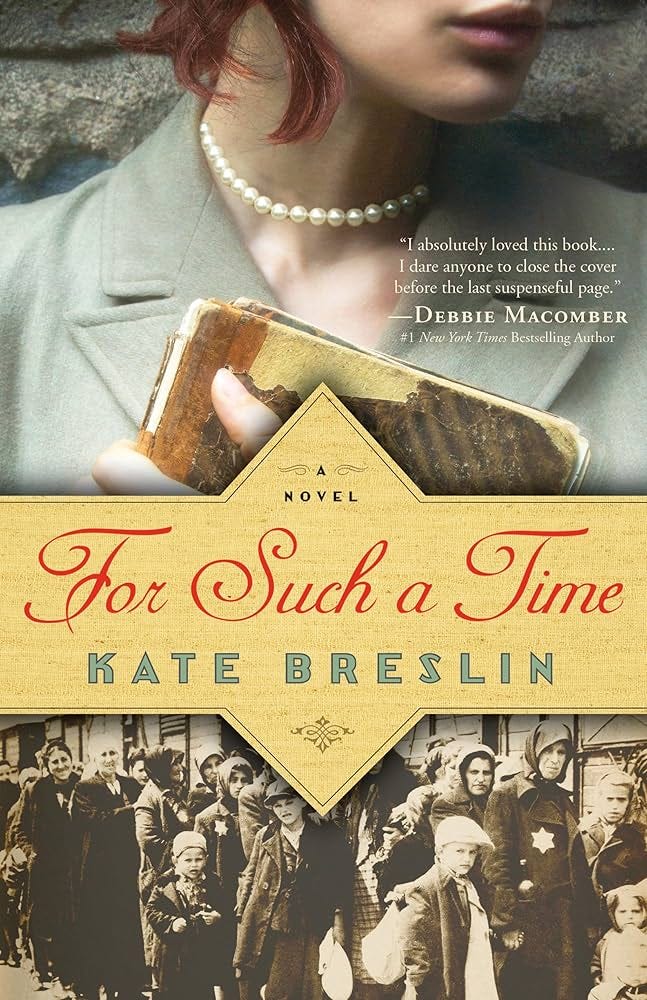

Kate Breslin's romance novel For Such a Time takes the Holocaust and turns it into a feel-good melodrama about the transcendent virtue of Christian saviors. If you read that and say to yourself, "wow, that sounds offensive and stupid," then you are more perspicacious than the Romance Writers of America, which short-listed the book for several awards when it came out in 2015. And you're also, perhaps, more discriminating than the Oscars, which, twenty years back, handed their Best Picture accolades to Breslin's spiritual predecessor in the white-savior Holocaust genre — Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List.

—

If you like my work, this is a good time to become a contributor! There’s a 40% off sale; $30/year. Help me keep scribbling about art and politics and our accelerating hellscape, at a low price!

—

Schindler's List has by this point been more or less canonized as a moral and aesthetic triumph; its rating on Rotten Tomatoes is a virtually unanimous 96% fresh. Breslin's novel has encountered more skepticism; Sarah Wendell of the romance review site Smart Bitches, Trashy Books summed up the case against in a letter to RWA that quickly went viral. But while Breslin isn't as celebrated as Spielberg, the two are engaged in much the same project of whitewashing the Holocaust.

The high concept of For Such a Time is a retelling of the Purim story in a German concentration camp. An SS Commandant, Aric, falls in love at first site with a Jewish woman, Hadassah (or Stella), when he sees her being dragged out to be shot by a firing squad, because nothing says "meet cute" like "war crimes." Due to a mix up in papers, Aric thinks Hadassah is Aryan, so he saves her and installs her as his secretary. And, oh, possibly, so much more.

Aric doesn't take advantage of the situation though, because he's a wounded, honorable man, and, also, #NotAllNazis. Despite herself, Hadassah finds his dashing good looks and compassion "laying siege to her emotional armour with battlefield vengeance," in one of Breslin's especially unfortunate metaphors. Other SS officials are nefarious and smell bad; Aric is of good odor in every way. Hadassah's love actuates his essential goodness, and eventually the two save a trainload of more or less undifferentiated Jews, who provide the warm, fuzzy backdrop for the final romantic clinch.

The real hero of the story, though, is not Aric, the Gentile, but rather Gentility itself. For Such a Time is an inspirational romance, which is to say, it's Christian. Hadassah is pursued through much of the book by a Bible which keeps mysteriously appearing in her moments of despair. The Bible is an edition combining Old and New Testaments, and while Hadassah mostly reads the familiar Jewish bits, she occasionally flips to the Christian sections, which duly inspire her to attempt to save the concentration camp victims. It takes Jesus' words to teach a Jew how to love her people.

When Hadassah's uncle declares at the end, "God is on our side," the God he's talking about, despite himself, is the New Testament one. The miraculous protagonist of the story, making Nazis good and rerouting trains from Auschwitz, is Christianity. Jews are saved by Jesus. Which means, queasily that the novel envisions rescuing Jews from genocide by making Jews, as Jews, disappear. How can the Nazis kill the Jews, if they all convert to Christianity first? (Though, of course, Nazis did cheerfully kill Jewish converts without Christ intervening.)

Schindler's List doesn't proselytize, which is a point in its favor. But there's no denying that, as in For Such a Time, there's an (at least nominally) Christian savior. Spielberg throws in a splash of red in his black and white film so you can identify a little girl killed by the Nazis—but Schindler's List isn't her story.

Instead, the bodies are piled up like cordwood to make the hero ever more heroic. The last famous scene of the film seems painfully telling. Schindler accuses himself of not doing enough while the Jews he saved huddle around to reassure him that he's a good ally and a good person. It's the film's melodramatic money shot; the moment when Schindler's virtue is recognized and verified—and in which the moral order of the film, and of the universe, is similarly validated.

Not coincidentally, For Such a Time, has a parallel sequence, in which Aric acknowledges that he may have to face justice for his crimes, and Hadassah's uncle Morty tells him "You won't face it alone, my son." The Holocaust, and Jewish suffering, give Jews the moral authority to provide absolution, and to recognize the essential humanity of non-Jews, even when (or rather especially when) those non-Jews doubt their own goodness. Without the Holocaust, how would you know that Schindler and Aric were heroes? Putting Jews in ovens is sad, but sometimes that's the price you have to pay for Gentiles to feel good about themselves.

Schindler was a real person — but then, Aric is based on King Ahasuerus, a Biblical character with some historical roots. There have always been people who have performed good acts even in difficult circumstances. But there's something obscene in using that fact as a way to make genocide into an inspirational growth experience for oppressors, over and over and over again. The Holocaust doesn't have a happily ever after. For Such a Time deserves ridicule, not awards, for suggesting that it does — and so does Schindler's List.

--

This essay appeared in Playboy a decade ago. It’s no longer online, but I think it’s still relevant—perhaps even moreso given the last year and a half of US politics around Gaza. The narrative congruity of For Such a Time and Schindler’s List speaks to the way that evangelical Christofascism and liberalism can come together around the idea that Jewish people are there to make non Jews feel good—a faux moral stance that can sideline Jews and normalize atrocity.

The Israeli right has taken advantage of this gentile savior fetish—and its concomitant positioning of Jews as eternal victims—to buttress its ethnonationalist violence at the expense of Palestinians and Israel critics (definitely including Jews). Netanyahu cosigning antisemitic bullshit doesn’t change the fact that it’s antisemitic bullshit, though. No matter what the genocidal right wing in Israel says, Jews out here in the diaspora would be a lot safer if gentiles were less obsessed with saving us.

I always hated these kind of movies, though I didn’t see this. I viscerally hated them because they must be glamorizing what is a crystallization of the greatest horror. If they are not so horrible that we cannot watch them, then they lie.

All copies of the movie you describe here should be burned.

Any movie depicting the Holocaust should be so horrible we cannot watch it without going mad or at least never think about anything the same way. ‘Zone of Interest’ is a movie that might help people understand this, but somehow a lot of people still did not understand it.

I thought ‘Downfall’ depicted an important truth about the Nazis, and these are the kinds of movies people should have made about that time but it’s probably too late. Maybe nothing Hollywood has ever produced ruined people’s grasp on reality more than their movies about this period.

I suppose a lot of things people make movies about are like this, but this type of movie has done the most damage to people’s understanding of history. If it’s understandable people would want to make movies about the Holocaust but they should come with a caveat so people understand that they can never understand the truth of what was actually done in the Holocaust through anything that they can tolerate watching, let alone enjoy.

The entire concept of "inspirational romance" in a book as described here is appalling. That this is the type of evangelical currently holding sway over so many Americans depresses me more than I can say.