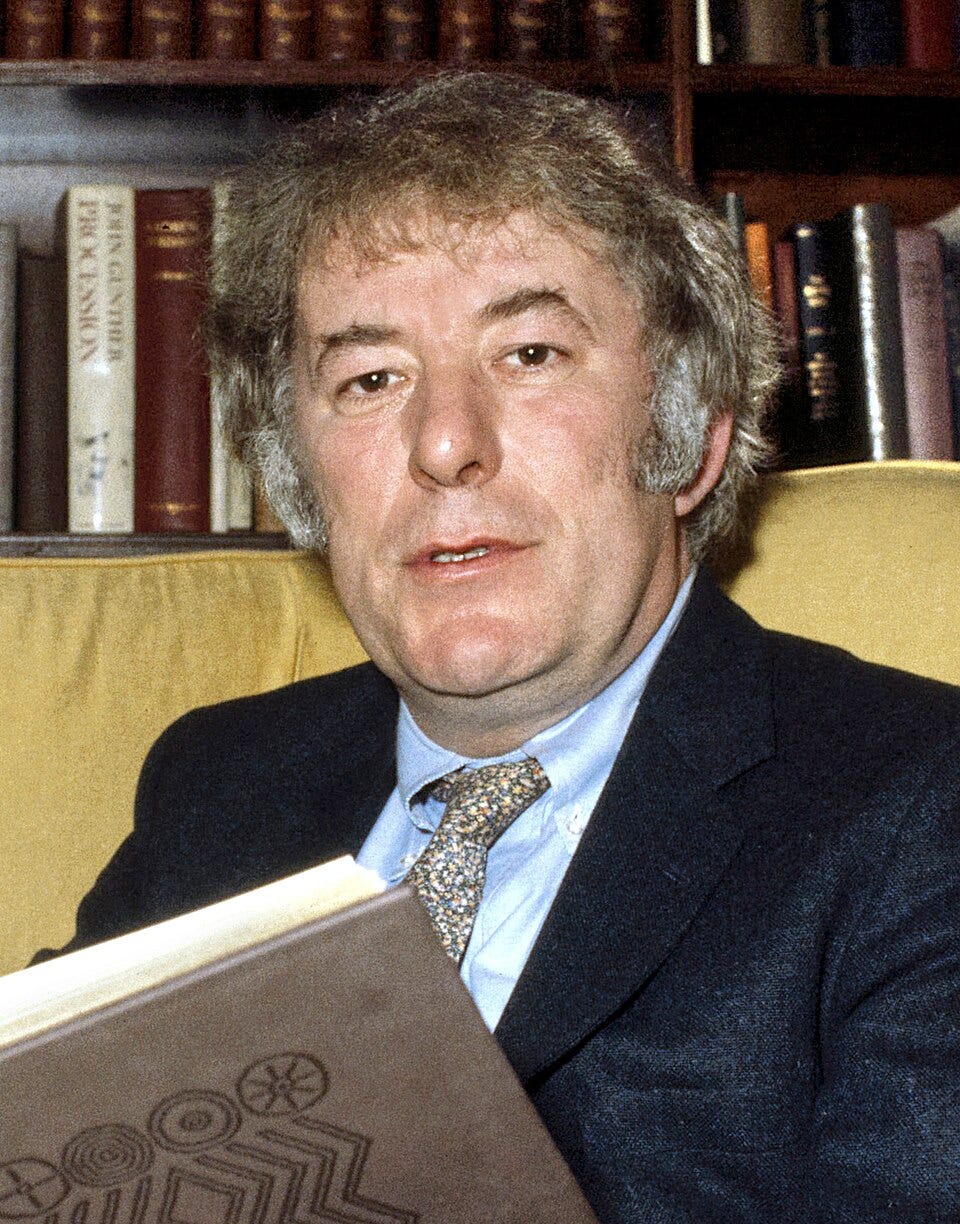

Seamus Heaney, Great Poet, For Better & Worse

Why I don’t love “Summer Home”

I’ve never exactly been a fan of Seamus Heaney’s poetry. He’s got obvious and enormous technical gifts, and he uses them to write very poetryous poetry, brimming with landscape and spirituality and strong clotted chunks of vocables.

Which is perhaps what puts me off; the great poet vibrating in the consonants and self-mythology feels overdetermined and a bit tiresome by the second half of the 20th century. One Yeats can be forgiven. Two starts to look like carelessness.

If that seems unfair…well, I also sometimes feel it’s unfair, and return to Heaney every so often to see if I can’t find it in me to be more charitable. The poem “Summer Home” did not make me more charitable—but it’s an interesting example of why I find Heaney off-putting, not least because it’s Heaney writing about why he’s off-putting.

—

Poetry posts are not the most popular things, but I enjoy writing them. If you enjoy them too, consider supporting my scribbling! Paid subs are $5/month, $50/year.

Great marriage

The poem was published in the 1972 volume Wintering Out; per David Fawbert’s excellent online resource guide, it is set in 1969, when the Heaneys were summering in France as a condition of a literary award. Heaney and his wife Marie had two children at that time; Michael born in 1966 and Christopher born in 1968.

Summer Home

I

Was it wind off the dumps

or something in heatdogging us, the summer gone sour,

a fouled nest incubating somewhere?Whose fault, I wondered, inquisitor

of the possessed air.To realize suddenly,

whip off the matthat was larval, moving

and scald, scald, scald.

Summer in rural France with two kids under three was not an idyll, as it turns out. The first section of the poem begins with Heaney trying to locate the source of a foul smell. He finally figures out that the stench is coming from under the front door mat, where larval insects are swarming. The final line, “and scald, scald, scald” is a domestic crescendo of relief and violence; the stink is coming from the home itself, prompting Heaney to burn it out.

II

Bushing the door, my arms full

of wild cherry and rhododendron,

I hear her small lost weeping

through the hall, that bells and hoarsens

on my name, my name.O love, here is the blame.

The loosened flowers between us

gather in, compose

for a May alter of sorts.

These frank and falling blooms

soon taint to a sweet chrism.Attend. Anoint the wound.

III

O we tended our wound all right

under the homely sheetand lay as if the cold flat of a blade

had winded us.More and more I postulate

thick healings, like nowas you bend in the shower

water lives down the tilting stoups of your breasts.

Part I is an ominous foreshadowing of turmoil; II and III describe what has been ominously foreboded. Heaney and his wife are fighting, though over what isn’t exactly made clear. She is crying probably in the bedroom as he brings her flowers to try to comfort her and/or patch up their quarrel. At night they have what sounds like ambivalent sex (“lay as if the cold flat of the blade/had winded us”). Afterwards Heaney watches his wife in the shower; “thick healings” suggests arousal; he also seems to queasily “postulate” the possibilities and pleasures of make-up sex, where the fight is the prelude to the pleasure.

IV

With a final

unmusical drive

long grains begin

to open and splitahead and once more

we sap

the white, trodden

path to the heart.V

My children weep out the hot foreign night.

We walk the floor, my foul mouth takes it out

On you and we lie stiff till dawn

Attends the pillow, and the maize, and vineThat holds its filling burden to the light.

Yesterday rocks sang when we tapped

Stalactites in the cave’s old, dripping dark

Our love calls tiny as a tuning fork.

The concluding sections of the poem elaborate on the themes of love as pain and release. Section IV uses natural metaphors of splitting and separation as a kind of double entendre; grains coming apart could be the couple splitting apart or could be the opening that leads to sex. Similarly, section V recounts an ugly night, with the children crying and the parents arguing, before shifting back to the previous day, with the final off rhyme suggesting a fragile, odd beauty in darkness or a hope ringing out from despair: “Stalactite in the cave’s old, dripping dark/Our love calls tiny as a tuning fork.”

Not liking what I’m supposed to not like

Heaney/the narrator isn’t supposed to be a likeable figure in “Summer Home.” The poem is about his anger, his impatience, his lust, and how those things squirm around each other, like the larvae under the mat. The ugly exhilaration of pouring the boiling water on the insects is echoed in the writhing concupiscence with which Heaney watches Marie bend in the shower (imagining her breasts, semi-ironically(?) as stoups, or basins for holy water). It also perhaps is linked to the angry words that spill from him after trying to comfort his own larval humans. The foul stench is in part a metaphor for the foulness inside him, which is mixed up in his own love and his own house.

I’m not against poetry of imperfect spouses. I love this poem by Kamala Das, an Indian poet who was writing around the same time as Heaney.

The Maggots

At sunset, on the river bank, Krishna

Loved her for the last time and left.

That night in her husband’s arms, Radha felt

So dead that he asked, what is wrong,

Do you mind my kisses, love? and she said,

No, not at all, but thought, what is

It to the corpse if the maggots nip?

As with Heaney, maggots, and the attendant rotting meat, are a symbol of a marriage gone bad—in this case because of infidelity rather than quarreling. Radha has experienced divine passion and now her husband in comparison seems like an insignificant bug, not even worth loathing.

It’s notable that Radha’s nameless husband gets to speak for himself. Admittedly his question is just a set up for a punch-line, but you do get a sense of his subjectivity, even if it’s just a subjectivity of cluelessness. In contrast, you never really hear Heaney’s wife’s own words—unless you count her “small lost weeping” of “my name, my name.” Das’ language is much more casual and colloquial; as a result, it’s easier for the poem to open up and let some other person wander in and have his say.

In contrast, Heaney’s heightened diction turns every actual voice into the Voice of poetry, muscular, metaphorical. “We walk the floor, my foul mouth takes it out/ On you and we lie stiff till dawn.” What do they say to each other? What is this fight about? What foulness does Heaney actually articulate, and what does his wife answer? We don’t know; it’s drowned out by the bang of the blank verse.

The poem is in part about how Heaney’s bad mood and bad words overwhelm his wife or push her aside. But it’s also an enactment of that overwhelming; Marie is inaudible, and exists in the poem mostly as another word or set of words which Heaney builds and rearranges to get his poetic effects—ambivalence, messiness, transcendence. In the last two lines, Heaney says, “Our love calls tiny as a tuning fork”—an epiphany and reconciliation which occurs again without Marie speaking, or having a voice outside of their union (“our love”) or Heaney’s metaphors (“as a tuning fork.”)

The resolution of Heaney’s inner and outer turmoil, the solution to his anger and lust, is to turn Marie into his poem. She is no longer her wailing (which he translates only as his own name), nor is she her body. She is the sound of the poem itself.

This is, maybe needless to say, a very standard way for heterosexual male poets to handle the women they desire in their poems. Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” is about its own effort to subordinate the lover’s consciousness to the poet’s words. Yeats spent his whole career lamenting that Maud Gonne was her own person and trying to overwrite her individual self in the world with the image of her in his verse.

Heaney is by no means as big an asshole misogynist as Yeats; part of what he’s doing in “Summer Home” is condemning, or problematizing, his own misogyny in a way Yeats certainly never did. But criticizing the thing you’re doing doesn’t necessarily mean you’re not doing it, and Heaney’s love of a high poetry tradition, with its flowers, its nudes, its flowery metaphors for sex and its transcendence slotted in at the end, bigfoots his effort to think about how his frustration, his ambivalent cruelty, and his desire actually affect his wife.

I’m not saying Heaney isn’t a Great Poet. I’m just saying that Great Poets are not necessarily always my favorite poets. Like traditional marriage, the tradition can weigh you down.

The Prisoner

by Kamala DasAs the convict studies

his prison’s geography

I study the trappings

of your body, dear love,

for I must some day find

an escape from its snare.

It’s possible to admire a poet’s skill and still not like the result. The only image in this poem that I like is the cave- the rest is manipulation. The cave feels like a beginning, like returning to a place before (maybe before they had children?). Some men can’t take the backseat to their kids. They can’t stand not being the center of attention, of having to be the adult. Heaney sounds like one of those men, but he thinks the problem is something else. It’s just boring at this point. But maybe in 1972 the idea of a man taking responsibility for his part in an unhappy relationship was a new thing.

Thank you for writing about poetry.

I can forgive Seamus Heaney his poetical sins after I read many years ago a description in the Guardian of school age Irish girls walking up to him in the street in Ireland sharing poems they had read of his in school. The Guardian author couldn’t imagine witnessing a contemporary English poet being recognized and loved by random English school girls.

I have to admire an artist that attune with his culture. Of course you have to have the culture that values artists.