Spitting on Kissinger's Corpse as Conceptual Art

A group exercise in aesthetics and organizing.

After smug centenarian war criminal Henry Kissinger died last week, perpetually wrong pundit Matt Yglesias posted to express his discomfort with the outpouring of vitriol aimed at one of the 20th centuries great monsters.

Anyways, it seems like [Kissinger] was a bad guy, but when I see MIllenials or Zoomers getting mad about Henry Kissinger, I feel like it’s stealing boomer valor. Let them have their thing; our thing is Don Rumsfeld being bad.

Putting aside the fact that Yglesias actually supported the Iraq War, and putting aside the callousness of saying that Kissinger “seems like” a “bad guy”, Yglesias actually has a kind of fucked up point. It’s weird for powerful war criminals backed by the US policy and political elite to ever face any kind of reckoning. There’s an easily imaginable world in which Kissinger’s crimes were mostly publicly forgotten, and in which mainstream hagiographies drowned out the few left voices of dissent.

You can see an example of what that might have looked like in the response to Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s death. O’Connor wasn’t a genocidal monster on the order of Kissinger, but she was a highly partisan Republican who believed unhinged conspiracy theories and handed the presidency to Bush on the basis of them, setting up the Iraq War and our current Christofascist court.

Most people don’t know that about her, and the media and social media response to her death didn’t do a ton to educate them. That’s more or less what you’d expect. Attention spans are short, power protects its own, people tend to default to reverence and respectability when people die. So why was the reaction to Kissinger’s death so different?

The answer I think is that Kissinger’s death was the center of a lengthy, innovative, very successful conceptual art project—a big Kiss Off, you might say.

Arguing that Kiss Off was a conceptual art project might sound nonsensical to some of my readers. People tend to see conceptual art as an elite, highbrow, largely incomprehensible visual art movement confined to galleries, not as a sustained, diffuse, social media propaganda campaign. But thinking of Kiss Off as art is revealing—and I think it has lessons both for art and for left political activism.

Conceptual Art and Conceptualism

There’s a reason that conceptual art is generally classified as a snooty gallery thing. The most well-known practitioners tended to dematerialize art—turn it into ideas—in order to satirize, or question, or undermine, art institutions and art commodification. Their attention was focused on an intra-art dialogue which (whatever its other virtues (and I like conceptual art!)) wasn’t necessarily of much interest to people who weren’t interested in visual art traditions in the first place.

There are, however, other kinds of conceptual art. In particular, artist and critic Luis Camnitzer has argued, conceptual traditions in Latin America were focused not on dematerializing art as part of a dialogue on art, but instead on dematerializing art as a way to make it more distributable, more accessible, and, therefore, more political.

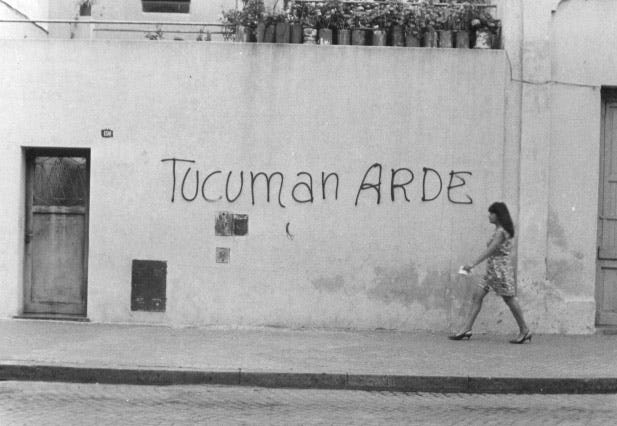

Camnitzer points to two “art projects” as iconic examples of what he calls Latin American conceptualism. The more art-like one was Túcaman arde (Tucuman is Burning), a 1968 exhibit/happening organized to counter dictator Juan Onganía’s sunny propaganda about life in Túcaman province.

The artists (including León Ferrari and Roberto Jacoby) advertised the event as a show designed to highlight a cultural profile of the province. Under that cover, they got favorable coverage from the (usually heavily censored) media. They also advertised using illegal graffiti—the first use of spray can graffiti in Argentina, Camnitzer says.

Image: Túcaman arde graffitti in Rosario, October 1968.

Then, when people arrived to the opening, they were greeted with text displays; these detailed interviews with residents about the desperate state of the province and research about wealth disparities. In some rooms, lights were darkened every ten minutes, representing the frequency of child deaths in the province. The show ran for two weeks in Rosario but was shut down quickly by police in Buenos Aires.

Túcaman arde was an example of art that wasn’t merely political, but actually became politics, or something close to it. It was as much a political rally/consciousness raising effort as a gallery show. Politics wasn’t really the content of the art; rather the forms of art were used to prepare people for (or lure people into) a political event.

Camnitzer coupled his discussion of Túcaman arde with a discussion of the Tumpamaros, a Uruguayan urban guerilla group which came close to functioning as an art collective.

The Tumpamaros was formed in part as a response to terror campaigns by right-wing gangs. They mostly avoided combat and terrorism themselves, however, because their goal was to raise public awareness and build public support through what they referred to as “armed propaganda.”

In its first major action, in 1963, the group posed as representatives of a neighborhood club and ordered a shipment of foods and sweets. They then hijacked the truck and distributed the food to locals. They also took over movie houses, and showed the captive audiences political material.

In other cases, they kidnapped officials or enemies, generally for a short time, in order to negotiate government prisoner releases. Prisoners were generally well treated. The one exception in which they killed Dan Mitrione, a US police chief who was sent to Montevideo to train local officials in torture techniques. Camnitzer says that the 1971 execution, “seriously damaged the image of the whole movement,” which had to that point mostly been scrupulous about avoiding violence.

Political Dematerialization

Both Túcaman arde and the Tumpamaros dematerialized, or broke down, barriers between the gallery and public life. Their “art” was aestheticized political action, which refused to confine itself to an elite, contemplative public or rhetorical space. They also dematerialized the artist, in the sense that the artist as genius largely vanished, to be replaced by a semi-anonymous artist as citizen, or even artist as revolutionary. And finally, for both groups, art itself dematerialized into a kind of aestheticized information, closer to a political speech, a political cartoon, or an op-ed than to even a work of “political art” like (for example) Picasso’s Guernica.

I think by now it should be somewhat clear how this kind of conceptual art applies to the outpouring of coordinated loathing that greeted Kissinger’s death. In some ways, in fact, you could argue that Kiss Off was even more successful in dematerialization than the examples Camnitzer cites , inasmuch as it had no one creator or group of creators, no location in time or space (except for the prompt of Kissinger’s death), and was not by and large even recognized as art (if you don’t count this essay.) The art project was a single idea—“Kissinger is a disgusting war criminal”—which was then elaborated on in a communal endeavor in which artist and audience were blurred, and indeed in which the goal of the art was to make the “audience” into artists and political subjects/actors.

To create successful art that exists without audience, without form, without institutional support, without artists, without recognition as art, but with political power and aesthetic force, is a remarkable achievement. It’s worth looking, briefly, at how it was created.

An Anatomy of Jumping on Kissinger’s Corpse

Kissinger’s role in the genocidal secret bombing of Cambodia, in the overthrow of Allende’s democratically-elected government in Chile, and in numerous other genocides and atrocities, has been well known for decades—in fact, since his tenure in office in the late 60s and 70s. Nonetheless, the mainstream press and the foreign policy establishment continued to treat him as a master diplomat and/or a fun celebrity.

But there were dissenters who, over the years, worked to undermine Kissinger’s reputation and his legacy. Gary Trudeau regularly lambasted Kissinger in his cartoons during the 1970s, for example.

Seymour Hersh wrote a brutal takedown of Kissinger in a 1983 book which reportedly enraged Kissinger himself. Christopher Hitchens wrote a similar indictment in 2001. (Hersh has gone on to embrace disgraceful genocide denial; Hitchens embarrassingly supported the Iraq war before his death; they may have betrayed themselves, but they were still right about Kissinger.)

Hersh and Hitchens were (at least at the time of their respective books) left journalists. But it wasn’t just progressives who came for Kissinger. In 2003, at a party hosted by Barbara Walters, with Kissinger in attendance, former news anchor Peter Jennings, famous for buttoned-up objectivity, shouted out, “How does it feel to be a war criminal, Henry?” (Kissinger said nothing, because he’s a fucking coward.)

Most famously, perhaps, celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain wrote a scathing assessment of Kissinger in his 2001 memoir, A Cook’s Tour.

Once you've been to Cambodia, you'll never stop wanting to beat Henry Kissinger to death with your bare hands. You will never again be able to open a newspaper and read about that treacherous, prevaricating, murderous scumbag sitting down for a nice chat with Charlie Rose or attending some black-tie affair for a new glossy magazine without choking. Witness what Henry did in Cambodia—the fruits of his genius for statesmanship—and you will never understand why he’s not sitting in the dock at The Hague next to Milosevic. While Henry continues to nibble nori rolls and ramaki at A-list parties, Cambodia, the neutral nation he secretly and illegally bombed, invaded, undermined, and then threw to the dogs, is still trying to raise itself up on its one remaining limb.

Trudeau’s cartoons, Jennings’ spontaneous denunciation, Bourdain’s passionate personal essay, can all be seen as political art, or as aestheticized political statements. They were, arguably, inciting events, and inspirations for the broader project of pissing on Kissinger upon his death.

Henry Kissinger Is In That Thing

That project, again, had no one real architect. A Henry Kissinger death watch seems to have occurred to a number of people more or less simultaneously in the last few years. Jack Mirkinson began a blog in 2021 complaining about Henry Kissinger’s longevity when various less repulsive figures (including Kissinger’s brother) died. A few months later, in December 2021, an anonymous 26-year-old Peruvian art student (perhaps influenced by Latin America’s conceptual art tradition?) started a twitter called “Is Henry Kissinger Dead?” The account would tweet out the word “No” (or NOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!!) at intervals. Until, on November 29, it finally tweeted, “Yes.”

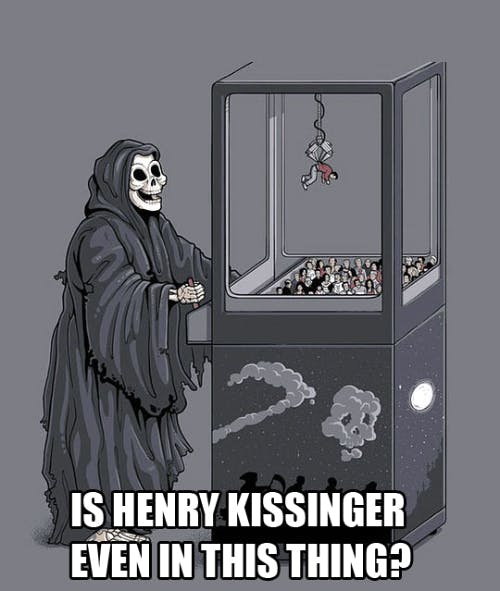

The preparation for Kissinger’s death wasn’t orchestrated by just one or two people, though. For years, whenever a beloved (or even less beloved) figure died, Kissinger would trend as tens or hundreds of accounts, big and small, regretted that he was still living and posted memes—the most famous showing a skeletal death at a claw machine, asking plaintively, “Is Henry Kissinger even in this thing?”

Kissinger trending would then prompt people to revisit why he was horrible, often by posting Bourdain’s quote. Thus, the running gag was also a form of political messaging—and of political, and artistic, organizing. Every celebrity death was an opportunity to remind, to rehearse, and to try out and disseminate aesthetic strategies and political talking points.

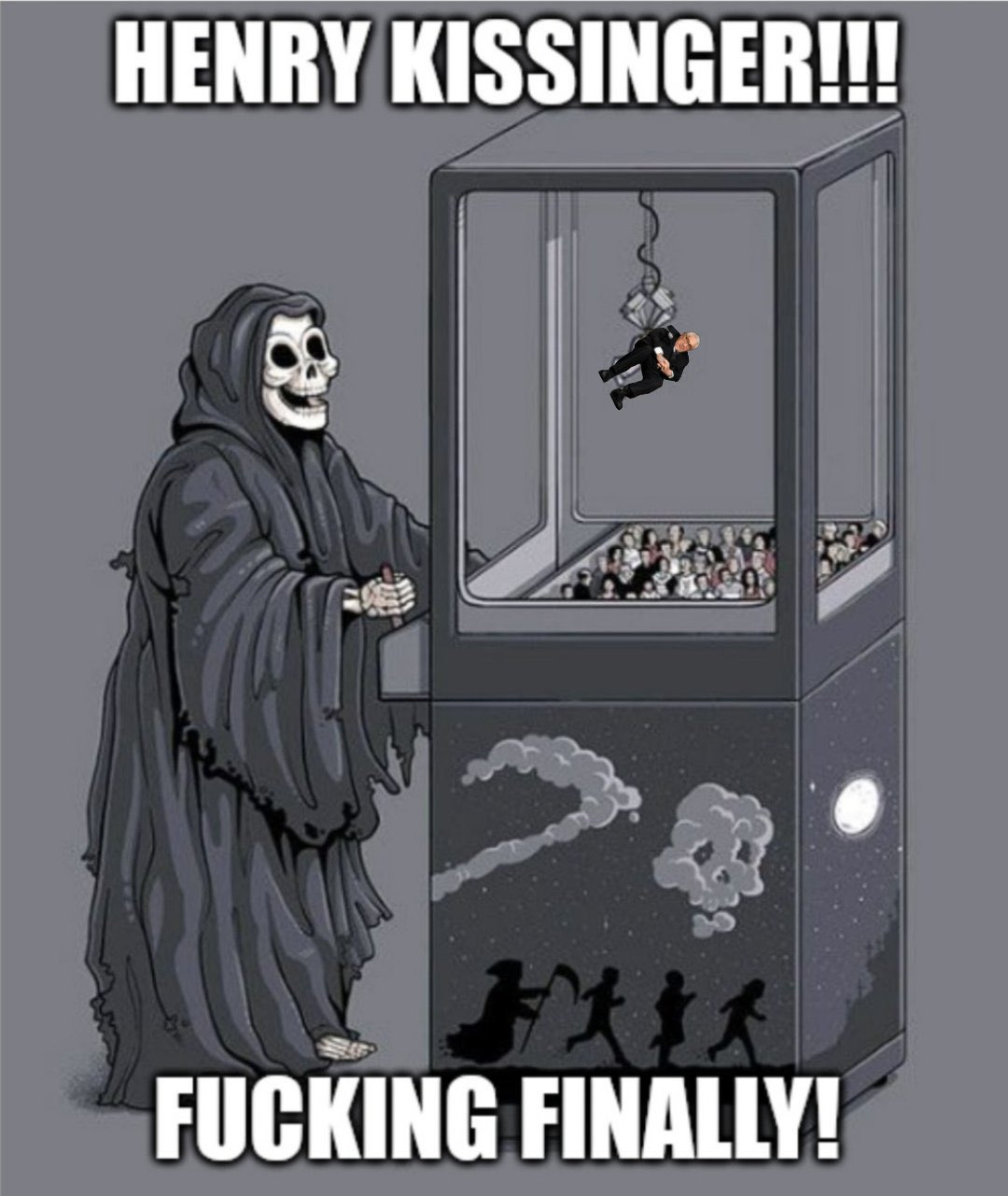

When Kissinger died, people were ready. Memes were quickly updated.

Doonesbury, Jennings, and Bourdain were requoted and discussions of them reshared, both on social media and in the progressive press. People pounced on and mocked hagiographic obits (like the one in the NYT) and amplified more honest and vicious assessments, like Spencer Ackerman’s in Rolling Stone (“Henry Kissinger, War Criminal Beloved by America’s Ruling Class, Finally Dies”) and Lex McMenamin’s in Teen Vogue, (“Henry Kissinger Was a War Criminal Responsible for Millions of Deaths.”) The socialist magazine Jacobin unveiled a whole book about Kissinger’s murderous career, which they had prepared especially for his death; it was widely discussed and cheered on social media—as the editors knew it would be.

Kiss Off, then, was inspired by some artists, some journalists, some anonymous and dedicated social media voices, some casual passersby. It had no one source or form, but picked up and promoted a variety of particular works of art—memes, quotes, cartoons, ideas. It existed in anonymous posts, and in carefully curated and planned works of political agit-prop and journalism.

More, this disaggregated, dematerialized work of collective art and protest was highly successful in its purpose—which was to drown out the usual voices demanding “civility” on the death of important genocidal schmucks, and to help permanently affix the label “war criminal” to Kissinger’s bloated corpse. The New York Timeses and the Yglesiases will still try to downplay Kissinger’s evil, of course, and history doesn’t have a final, final verdict—you have to fight the same battles over and over, even over Stalin, even over Hitler. But there’s little doubt that this particular art project, over years, went a long way towards raising awareness of Kissinger’s evil, and of the evils of US imperialism and “realpolitik” which he represented.

Dead Kissinger Lessons

It’s difficult to see the project as a success if you don’t see it as a project, though—which is one reason why I think it’s useful to talk about Kiss Off as a piece of conceptual art. Another is that conceiving of it as a single dematerialized aesthetic intervention in politics allows us to see how its successes—aesthetic and political—might be repeated.

Social media is often pilloried (on the left, too) as a demobilizing distraction, or as a disseminator of disinformation. It’s denounced as a source of mob attacks, as an addiction, and as a walled preserve divorced from real life concerns (the last a charge that’s often directed at conceptual art, as it happens.)

But Kiss Off shows how social media can be a successful crowdsourced method of political organizing and/or artistic creation—in part because such political and artistic projects dematerialize the barriers around social media too. Meatspace activism (Jennings insulting Kissinger), regular media journalism (Ackerman’s obituary), political art (Doonesbury), can be circulated along with other memes and social media jokes/art projects, building on one another and infiltrating traditional media sources that might be indifferent to left messaging, but are willing to report on the memes or the event.

Visual artists, poets, and basically all artists have long struggled with how to, and whether, to incorporate politics into art, and with how to make elite art spaces less elite and more open to the public. Henry Kissinger’s death suggests some strategies—at least to the extent that it provides a blueprint of what success might look like.

Kiss Off shows that political cartooning, political writing, political protest can all be repurposed and become part of a broader political project, if they are sufficiently memorable (and meme-able) and happen to catch the right audience’s eye.

Anonymous, more purely conceptual work (like that Is Henry Dead twitter account) can have a broad impact if you pick the right topic, the right idea, and are willing to eschew credit and most traditional art channels. But whatever form the art takes, art as mass politics requires a willingness to dematerialize one’s own artistic function or artistic identity—to take cues from an audience which is also effectively a group of other creators.

Political actors too can take lessons from Kiss Off. Specifically, the evisceration of Kissinger suggests the value of embracing aesthetics.

Political pundits are sometimes nervous about incorporating art into messaging. They may feel that aesthetic approaches trivialize political causes (thus the outcry at climate activists targeting famous art). They may nervously remember Walter Benjamin’s argument that fascism is the aestheticization of politics. But, contra Benjamin, the truth is that any mass politics is in part an exercise in aesthetics, and if there’s a war of art, it’s best to grab the paintbrush (or the meme generator) quicker, and more inventively, than your foes.

In addition, Kiss Off is a reminder to leaders that the masses aren’t just there to listen—and perhaps to the masses that leaders and traditional institutions can be useful allies. Mainstream journalists, cartoonists, chefs, random social media accounts—they all worked for years to ensure that when Kissinger finally croaked, he would be greeted with cheers, jeers, vicious obits, and vicious memes. The result was funny, scabrous, exhilarating, weird, unexpected, satisfyingly expected and lovely. It shows that if we work together to bring down the barriers between us, we can make great art, and great politics too.

Did you see the copypasta text message about Kissinger? I don’t know how to link to it here but it was all over Twitter. I had never heard of copypasta before this, but it’s definitely a work of art. The author had prepared it a couple of years ago, so it was ready to go as soon as the news hit.

I LOVE this idea,, and I'm trying to think of other examples.