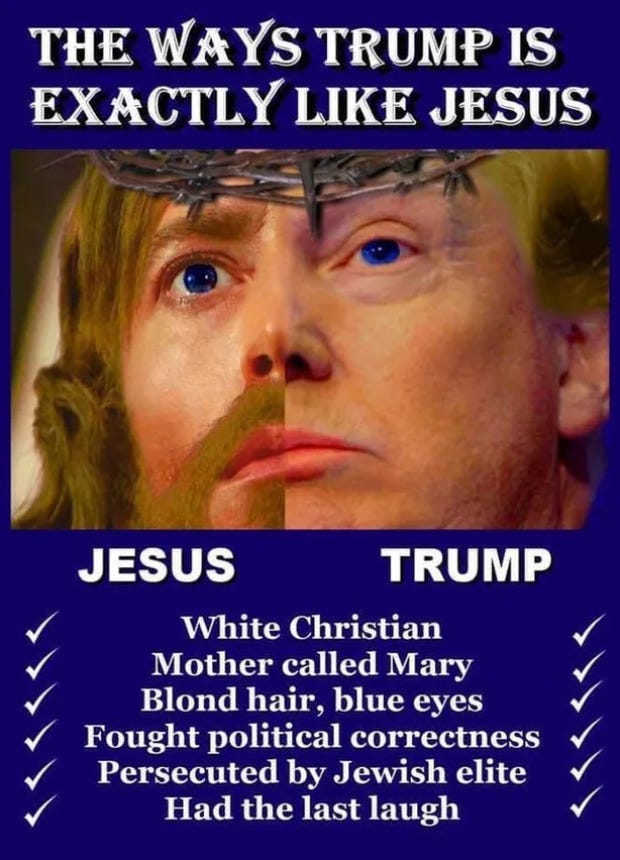

The Chosen One

White evangelicals like Trump because he embodies their Christian ideals of violence and cruelty.

I published this in 2019 Medium; I think it’s still relevant, so I thought I’d share it with substack readers. If you like my writing, consider becoming a paid contributor so I can keep on keeping on.

_____

Evangelical support for Trump is consistently framed not just as a puzzle, but as a contradiction. Trump’s history of raping and sexually assaulting women, his ugly rhetoric, his indifference to the suffering of children, and his transparent lack of faith, are presented as being out of step with evangelical commitment to Biblical morality and Christian values.

Two reported articles in the Washington Post follow the usual script. The first, by Julie Zauzmer, is based on interviews with 50 Trump supporting evangelicals in battleground states, and concludes that Trump’s unprecedented support among evangelicals is unlikely to diminish. Trump won a higher percentage of evangelical white Christians than John McCain or George W. Bush (an evangelical himself) in 2016, and in 2019 a Pew survey still put his support in the demographic at 70%.

Evangelicals find Trump appealing, Zauzmer says, because he “sees America like they do, a menacing place where white Christians feel mocked and threatened for their beliefs.” He is also, “against abortion and gay rights and…has the economy humming to boot.” Similarly, in a reported personal essay, Elizabeth Bruenig (a Catholic convert from evangelicalism), writes that “Trump’s less-than-Christian behavior seemed, paradoxically, to make him a more appealing candidate to beleaguered, aggravated Christians.” Evangelicals feel oppressed by a culture that forces them to sell wedding cakes to gay people and watch television programs where single women occasionally have sex. Christians are supposed to turn the other cheek; they need an agnostic bully to stand up for them.

Neither of these articles are apologies for evangelicals. Though they are both framed in the neutral language of objectivity, it’s obvious that the authors are not supporters of the President, or of his policies. But they also are both framed by the supposition that Christian values and Trump values are in tension — that they exist together “paradoxically” as Bruenig says. You can hear the incredulity in Zauzmer’s piece as she tries to get evangelicals to criticize Trump for his abuse of women, for creating concentration camps at the border, or for just about anything other than the perhaps unfortunate phrasing of his tweets.

Evangelicals, though, don’t want to criticize Trump. They see him as one of their own. That’s not just because of his vocal (though probably not heartfelt) antipathy to abortion and marriage equality. It’s emphatically also because of his vicious (and very heartfelt) immigration policies. “The places they’re housing [immigrants], honestly, if they’s so uncomfortable, they shouldn’t have come here,” one woman tells Zauzmer. Another man whines about how there’s no longer prayer in public schools and insists the “country is losing the values that we once had.” Make America Great Again is a slogan white evangelicals embrace with a visceral, holy passion.

Evangelicals, one begins to suspect, don’t support Trump despite their faith. They love him because he and they share the exact same religious commitments.

This is the argument of Yale sociologist Philip Gorski. Gorski notes that many white evangelicals embraced Trump in the primary, preferring him to candidates like Cruz and Rubio with a much clearer record on issues like abortion. Why did white evangelicals like Trump so much? Gorski asks. The answer is straightforward. They supported him, “[b]ecause they are white Christian nationalists.”

Gorski continues that evangelicals “were attracted by Trump’s racialized, apocalyptic, and blood-drenched rhetoric” because “it recalled an earlier version of American religious nationalism, one that antedated the softened tones of modern-day ‘’American exceptionalism’ first introduced by Ronald Reagan.” Gorski concludes that “Trumpism… is as a reactionary and secularized version of white Christian nationalism.

White Christian nationalism has “four key elements” Gorski says. These are “(1) racism; (2) sacrificialism; (3) apocalypticism; and (4) nostalgia.” Gorski notes that historically white Christians in the US have turned faith into a weapon of blood and conquest; the war of extrermination against Native peoples was portrayed as a religious crusade of purification, done in the name of a God indistinguishable from whiteness. Slavery and subservience to whiteness were also justified as a Biblical sacrament. White Christians saw themselves at the center of a mighty narrative, purifying and subjugating sinful modernity in the name of an unstained, idyllic past. Trump’s ICE agents carry on the holy crusade of punishing all the stained, “shithole” people for the unforgivable sin of not being white.

Theologian Willie James Jennings’ arguments in his book The Christian Imagination precede and buttress Gorski’s insights. Jennings notes that as Christianity became the religion of rulers and the powerful, “the Christian imagination was woven into processes of colonial dominance.” He elaborates

“Rather than a vision of a Creator arising through the hearing of Israel’s story bound to Jesus who enables people’s to discern the ways their cultural practices and stories both echo and contradict the divine claim on their lives, the vision born of colonialism articulated a Creator bent on eradicating people’s ways of life and turning the creation into private property.”

Christianity in this context was simply the name of power. The Cross was the thing you erected on the bones of your enemies to show you had taken their land.

If Christianity is white power, then assaults on white power and traditional hierarchies, are an affront to God. Evangelicals feel beleagured and dispossessed for the exact same reason that white nationalist like Richard Spencer feel beleagured and dispossessed. They believe that, as white people, they have the right to rule a white nation. The rage for purity is sometimes expressed through sexual taboos, and the demand for control over women’s bodies. But it is just as profoundly tied to an obsession with borders and the policing of non-white people.

That is why white evangelical blogger Erick Erickson was so infuriated by the New York Times’ 1619 Project, an extensive examination of the ongoing influence of slavery on injustice in the United States. Erickson said that the NYT opinion writers “profit from seeing things through racial lenses” — which in this case means that they viewed American history from the perspective of Black people. For Erickson and other white evangelicals, this is akin to blasphemy. For many white Christians, it is an article of religious faith that American history belongs to white people.

Erickson as it happens, did not vote for Trump. Thirty percent of white evangelicals didn’t. Some of them probably even agreed with the 1619 Project. To point out the Trumpism is inherent in white evangelicalism isn’t to say that all white evangelicals are evil. Nor is it to say that Christianity is innately corrupt or racist. Christians (especially Black Christians) have often worked for equality and justice in the US, and still do so today.

But it’s important to recognize that white Christian nationalism is not some sort of historical curiosity. When Trump says he will win his trade war with China because he is “the chosen one”, he is simply restating the longstanding white Christian belief that white people are divinely selected to subjugate everyone else. Some Trump critics — including some white evangelical Trump voters — have called this rhetoric blasphemous. But for many white evangelicals, a white man proclaiming himself the divine agent of racist retribution isn’t heretical. It’s a refreshing restatement of the basic tenets of their faith.

The 1619 Project documents how inequities in American health care, American prisons, American music, and even American traffic patterns are all the legacy of slavery and racism. It could have included essays on numerous other institutions — certainly including Christianity. There is no paradox in white evangelical support for Trump. On the contrary, Trump is their faith embodied. Who could better stand for a religion which has served as a positive justification for rape, torture, violence, and hate? White people’s Christianity was the morality of genocide and slavery. It’s only by erasing that history that Christian support for Trump can be presented as an aberration.