The King of Rock

Not Elvis.

A Chuck Berry-esque guitar opener leading into a shoulder-shurgging rock strut, while the chorus sings at some bleary distance, as if they wandered into the adjacent recording studio and were too stoned to find their way back out.

A lost track from Exile on Main Street, you guess? Nah; it's early B.B. King, from the mid-to-late 50s, performing a track by one of his influences, the great jump blues singer Louis Jordan.

King is of course a blues performer—but listening to his early work, you're reminded that the line between early rock and early blues basically didn't exist. Check out the raw rave up of “Shake It Up and Go” from 1952; harsh, driving, raucous rock and roll two years before Elvis was supposed to have invented it, with King's stinging guitar lines presaging—well, basically everything.

King had become an institution before his death, but there's nothing of the institution about this track's hip, microphone bruising strut. This right here — jump blues wedded to electric guitar, with nonsense lyrics ("Mama killed a chicken/she thought it was a duck"), recorded loud enough so that the amp sounds like it's going to expire — this, B.B. King is telling you, with cheerfully brutal conviction, is going to take over the world.

And so it did. Which is why King today is name-checked by just about every rock performer who's picked up an ax— Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, and Jimi Hendrix are the stars most often mentioned as his heirs, but Billy Gibbons, Joe Perry, and a host of others have lined up to pay tribute as well. Rock musicians love the King of the Blues—almost as if blues and rock, so intimately tied together in the 50s, never really did separate after all. Why are Eric Clapton and ZZ Top rock, anyway, if B.B. King is the blues? When Valerie June or Trampled Under Foot lean into one of those B.B. influenced solos, are they performing retro-blues or retro-rock? How can you tell?

All of which makes you wonder: if B.B. King performed music indistinguishable from rock in the 1950s; if he made music much like rock musicians of the 60s and 70s; if his influence now can't really be distinguished from that of the rock musicians who followed him—why exactly is he King of the blues, and the blues only? Why is his influence on rock only an influence? Why isn't he the King of Rock?

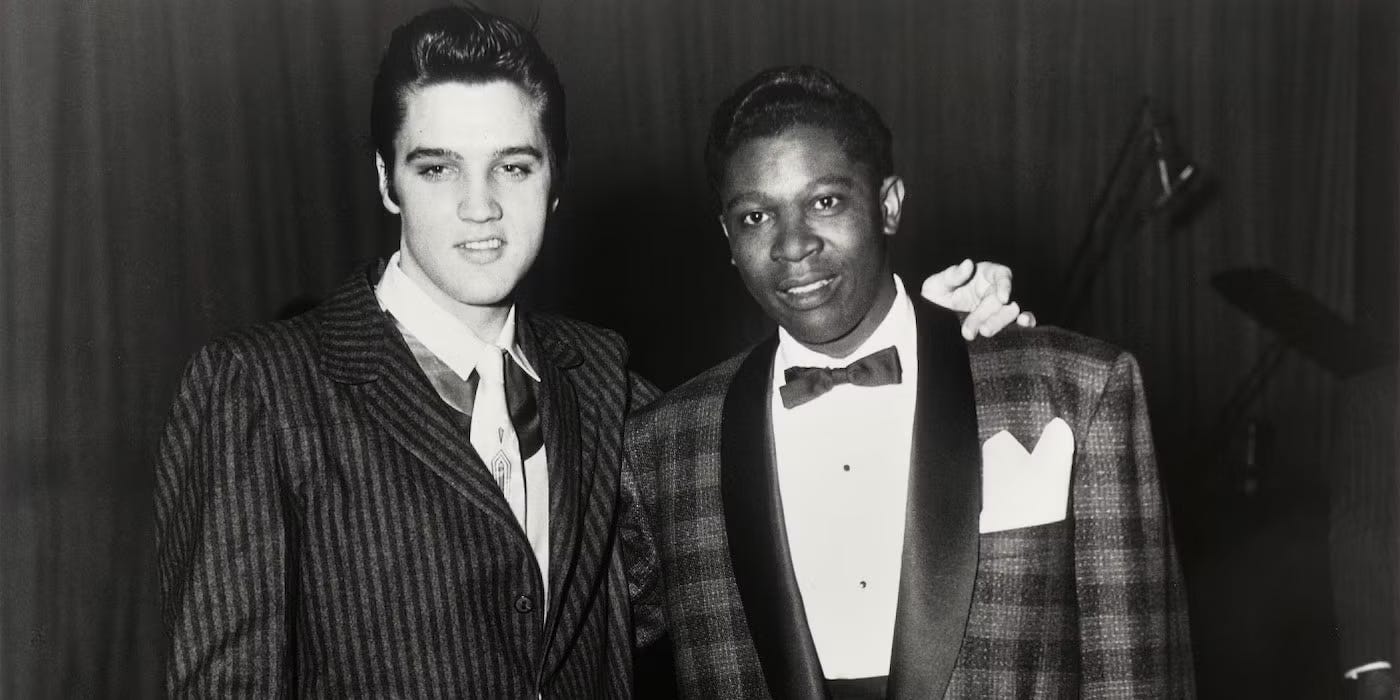

Of course, he's not the King of Rock because the King of Rock is that guy with the hips who came along a couple years after "Shake It Up and Go." Elvis had his own, jittery imitation of King and all the other jump blues and blues and R&B artists who had, together, and with some help from country musicians, put together the elements of the genre we know as rock.

Rock was a multi-racial music; King himself drew on Django Reinhardt as well as Louis Jordan. But the complicated strands of mutual influence over time got flattened out in the popular consciousness, and what was left was that iconic performer, the King, a white man playing music associated with black people.

And over time, that's the definition of "rock" that won out: black music played by white performers. The genre boundaries were never completely solid, of course—there was enough give that a Jimi Hendrix could slip through by playing psychedlia with white guys. But for the most part black performers who played rock, like Ray Charles, or Otis Redding, or Etta James, or Motown, weren't allowed to be rock. Instead they got classified as R&B or blues.

And so B.B. King, an innovator who synthesized music from disparate performers, became an influence—someone mainstream artists drew on to show their cred, rather than part of the mainstream himself. He's the tradition that geniuses riff upon; a blueprint from which innovators build their cannonical Exile on Main Streets or their "Layla"'s. Authenticity is bestowed on black musicians like a laurel, but it's often also a cage. As a roots musician, King's vitality and energy are figured as always already buried, waiting for someone to draw it out. In contrast, the Rolling Stones can be the swaggering young ever-relevant bad boys even on their umpty-umpth geriatric tour—and even if they never really recorded anything that grabbed onto the future and howled the way that "Shake It Up and Go" did.

As the tributes to him show, King was widely admired and venerated; he enjoyed his place in the blues, and his mastery of it. He didn't seem to need or want more accolades than he had; he didn't, for himself, need to be the King of Rock. But that doesn't change the fact that he has at least as much right to that title as Elvis, who was, for all his popularity, less innovative, less consistent, and less influential. Taking a moment to remember B.B. King as the King, period, no "of" needed, is more for our benefit than his. It's a reminder of what we miss when we put genius in a box made out of genre, or in one made out of race.

—

This ran some years back in Playboy; it’s no longer online. With Trump attempting to erase Black history wholesale, it’s worth remembering that such erasures themselves have an unpleasant and extensive history.

He may not have been crowned the King of Rock, but he definitely was known as the King of the Blues.

His vocal style and his trademark note-picking guitar runs on "Lucille" firmly established him as a top-selling R&B artist in the 1950s, and his reputation only grew in the years afterwards as so many celebrity fans sang his praises. It was a reputation hard won over years of personal struggle and setbacks, to say nothing of the racism of that time. Right up to the end of his life, he was touring and recording with a level of energy most other musicians only wished they had.

"Live At The Regal" manages to capture substantially his early sound and his relationship with his audience, while "Live At Cook County Jail" showed that even cons get the blues.

And through all of that, virtually no traces of egotism; he was friendly, approachable and thoughtful towards his audience in a way that put others to shame.

He started his career playing flimsy juke joints and ended it playing heavily attended engagements in stadiums and concert halls around the world. Not bad.

Thank you for the Black History moment.

Black music was pigeonholed cause of racism.

Michael Jackson’s album off the wall only won a grammy for R&B, cause Black musicians couldn’t be nominated in other categories.

Black musicians had to “cross-over” to be played on white stations.

I was at the James Brown and Friends concert in Beverly Hills in 1986. B.B. King was the friend. And MJ and Prince were in the audience and went up on stage. I couldn’t believe it. We were broke…and lived in San Diego- so I don’t even know how we were able to go…but I have never forgotten it!

Prince was the greatest rock guitarist of all time.

And MJ will always be the King of Pop.