The Music Cassie Never Got To Make

Abusers like Sean Combs destroy women’s lives and art.

Sean “Diddy” Combs, the mega successful rapper and producer, was convicted earlier this month of two counts of transportation for prostitution of his ex, singer Cassie Ventura. He was acquitted on charges of racketeering and conspiracy, and was not charged with assault, despite harrowing video evidence of him beating Cassie, and despite his lawyer acknowledging that he did commit domestic abuse.

There’s a lot of analysis out there of the verdict and the case against Combs. I’m not a lawyer, so I’ll leave that to others. I do think this case, though, highlights the way in which abusive men in the arts destroy the careers of women performers, and rob the world of their art.

This isn’t the way that MeToo discussions are framed in mainstream discourse. Usually, on social media and in just regular media, critics of MeToo will argue that abuse allegations derail the careers of important male artists like Kevin Spacey or Louis CK and prevent them from working or sharing their work.

No doubt there’s someone out there who believes that Combs is a genius and regrets that he will no longer make music. But his career in general has—like that of Harvey Weinstein—been more that of gatekeeper and financier than artist. And that means that, like Weinstein, his “work” has basically been defined by harassing, terrorizing, and derailing the work of more talented female artists.

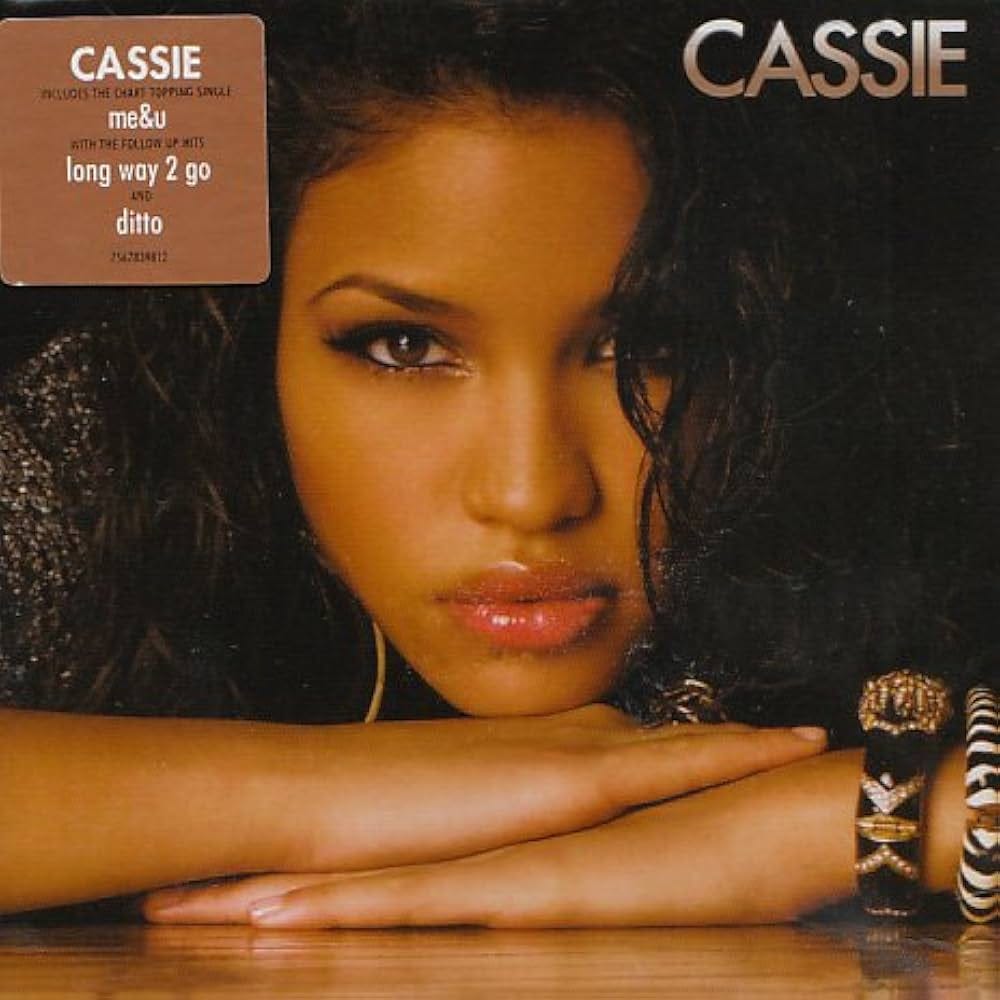

First among those is Cassie herself. The singer’s self-titled 2006 debut was a sublimely sexy electropop confection, with Cassie’s deceptively light vocals sliding seductively around Ryan Leslie’s bleeping and blooping production. In its high-gloss mix of innocent vulnerability, saccharine horniness, and buried desperation, all wrapped in hooks you can’t get out of your backbrain with a back-hoe, Cassie echoes and extends the fey baroque pop of Brian Wilson, the Carpenters, or ABBA.

Seven years later, Cassie released a mixtape which follows through on her promise while going in a completely different direction. RockaByeBaby is tough, head-nodding trip hop. A who’s who of 2010s rappers—Rick Ross, Pusha T, Fabolous— do their thing over deep beats, with Cassie’s voice serving as a stoned counterpoint, laid back, heavy-lidded, but still with an incongruous sweetness. It’s a shivery yang to the debut’s sugary ying, and a definitive statement that the genius on that first album was in fact Cassie’s as well as Ryan Leslie’s. One perfect album could maybe be an accident. Two completely different perfect albums and it’s clear that the artist could make a lot more than two perfect albums if she had the chance.

She didn’t have the chance, though. In a career that’s spanned almost two decades, Cassie’s released exactly one album, one mixtape, and a handful of singles and guest tracks. These incidental releases, while uniformly excellent, are also an exercise in frustration, which make you wish there were more Cassie albums out there.

I’d long wondered why Cassie—whose debut was a commercial and critical smash, and who has been cited by Solange and many others as an influence—did not become a breakout star to rival Beyoncé or Rihanna.

I don’t have to wonder anymore. In her testimony at Combs trial, the singer makes it clear that her relationship with Combs knee-capped her career as an offshoot of turning her life into an endless nightmare of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse.

Cassie started dating Combs in 2005 when she was 19 and he was 36. She signed to a 10 album deal with Comb’s Bad Boy records, but despite recording hundreds of songs, she never released a full length record after her debut. Instead, as his girlfriend, her main job became, according to her testimony, not singing, but arranging sex parties for Combs with male and female sex workers. If she expressed frustration, or did not want to participate in the parties, she said, Combs would verbally or physically abuse her.

Cassie wasn’t the only musician whose career Combs derailed. Dawn Richard, another amazing artist who started her career with Combs’ projects Dirty Money and Danity Kane, says that Combs sexually assaulted her, physically abused her by preventing her from sleeping or eating, and refused to pay her for her work.

Richard has been more fortunate in terms of recording than Cassie—she’s released a series of impressive experimental R&B albums since 2013 when she managed to escape from Combs’ influence. But it seems likely that she would have had more success, and made more music, if she hadn’t spent years fighting for her art and her life with a billionaire asshole who made it his business to destroy both.

People don’t talk much about the damage that people like Diddy, or Weinstein, or Louis CK, or Ryan Adams, can do to the careers of women in the arts. That’s not because the damage is negligible, but, contradictorily, because it is so thoroughgoing. Accusations of sexual harassment and violence affected the careers of Louis CK and Ryan Adams after they were already big names; they had large numbers of fans who wanted more of their art.

Performers like Cassie, and Dawn Richard, and D. Woods of Danity Kane, had their careers and their art stifled before they were able to produce much work or create much of a fanbase. Male abusers are able to establish themselves as great artists in part by exploiting the talents of the people they abuse, and in part because “male genius” is an established pop culture niche. Victims, in contrast, don’t get a chance to establish a reputation. As women pop stars, their success is typically attributed to their abusers even when their careers aren’t cut off in their infancy.

Part of the dynamic here can be attributed to what Kate Manne calls himpathy—the tendency of people (of all genders) to empathize with powerful men, and feel more sympathy for abusers than for their victims. Part of it is due to the material facts of patriarchy; men tend to have more access to money and to institutional power, allowing them to set themselves up as gatekeepers who women artists have to cater to or assuage if they want an audience.

Whatever the causes, though, the outcomes are predictable and ugly. Combs and those like him are framed as complicated geniuses, whose unfortunate, complex history as abusers robs us of their art. People like Cassie and Dawn Richard, meanwhile, become part of Combs’ story, not least because Combs did everything he could to make sure that they didn’t have the financial or emotional support they needed to make stories of their own.

Cassie and Richard have, despite Combs, made wonderful music, and both deserve to be more celebrated for their talent and artistry. How much more could they have done, though, if Combs hadn’t intervened? How many other great female singers, songwriters, and musicians never got a chance to make any music because Combs decided they shouldn’t?

Patriarchy harms women. It also destroys art by women, which is effectively half the potential art that can be made on earth. The albums Cassie didn’t make are a damaging loss in themselves. But they’re even more painful as a reminder of all the art, all the beauty, all the genius, and all the human flourishing that is destroyed when men like Combs use their power to make sure that only they can create, and that the only creation is hate.

Thanks for this excellent essay. I have been making the same point for a while, but neither as eloquently nor with such excellent receipts.

Thank you for this much-needed perspective. The backlash to MeToo has shown how deeply misogyny is entrenched in society. It makes us doubt the women who come forward and protect the men. It’s infuriating to me. (Another obvious example is Trump.)