The Poem That Wasn't There

On Steve Van Allen's lovely haiku from Five Fleas.

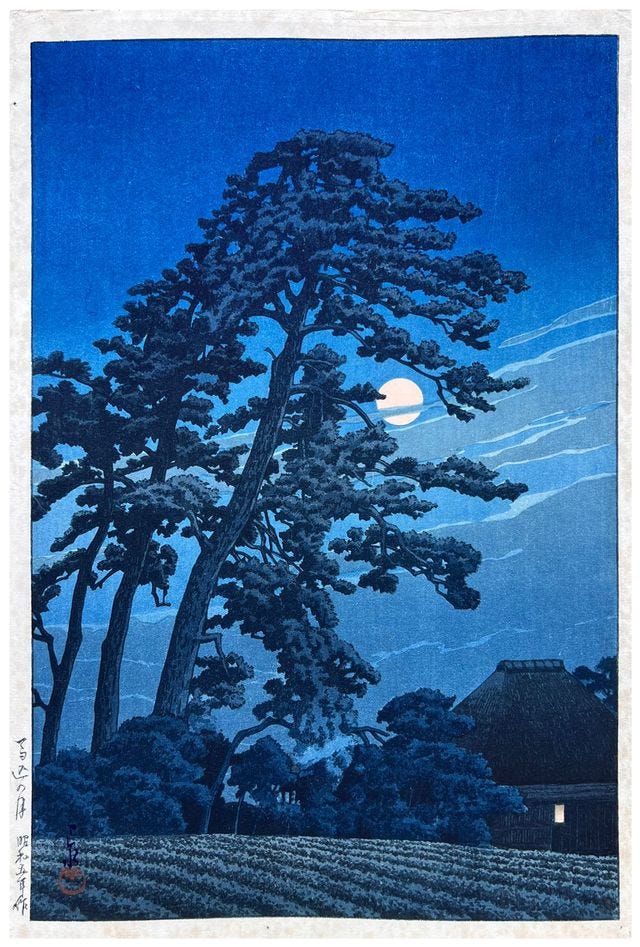

Kawase Hasui, Moon at Magome

I was able to carve out time to write this because of paid substack subscriptions. If you subscribed, thank you! If you haven’t yet and like this post, consider helping me write more like it!

_______

I’ve been publishing some short poems at Roberta Beach Jacobson’s site Five Fleas (Itchy Poetry). I’ve also enjoyed reading some of the other entries. One of my favorite is this haiku by Steve Van Allen.

Full moon glows

moving through twisted bare branches

as if they weren't there

It seems like a fairly simple, imagistic piece. The poet contemplates the full moon which he can see moving through tree limbs. As with many of the best haiku, though, there’s a good bit more going on.

The turn in the poem is the last line, “as if they weren’t there.” The moon moving through the branches is an optical illusion which slides through the tree like a ghost. The branches are real, so is the moon. But they’re not really occupying the same space.

The disjunction suggests or points to the transitoriness of the physical world. The illusion of non-existence reveals the truth that the branches, the moon, and the world are in fact illusory. Van Allen’s poem thematically echoes one of the most famous haiku by Kobayashi Issa

tsuyu no yo wa

tsuyu no yo nagara

sari nagaraThis world of dew

is a world of dew,

and yet, and yet.

The world is real and unreal, tangled together, like the moon in those branches. The last line of Van Allen’s haiku, “as if they weren’t there” is an oblique restatement of Issa’s “and yet, and yet.” The real world is a phantom, which can’t be grasped. “Yet” that insight is disavowed; the branches only look “as if” they aren’t real. The conditional is an acknowledgement that the poet is unwilling to acknowledge his own insight. The branches are there, but they aren’t, but they are. The poem erases the world, but its own longing for the world reflects the world, like the moon shining with the light of the sun.

Van Allen’s poem questions metaphysical or existential presence. But it can also be read as a meta description of its own processes. The full moon and the branches seem “as if” they are not there because they really are not there. A poem reflects the world (like the moon again), but it isn’t the world itself. The word “moon” isn’t the moon; the word “branches” is not a branch. The poet, like the moon, only seems to be touching the tree because the tree isn’t there.

This isn’t just philosophical; it’s literally true. The branches in the poem are at best an image of real branches. They exist only in the imagination of the poet or reader. The one truth in the poem, the thing that is solidly there, is absence. The branches aren’t there.

The moon floating through a poem that acknowledges its own unreality reminded me of the Mark Strand poem “The Prediction”.

The Prediction

That night the moon drifted over the pond,

turning the water to milk, and under

the boughs of the trees, the blue trees,

a young woman walked, and for an instantthe future came to her:

rain falling on her husband’s grave, rain falling

on the lawns of her children, her own mouth

filling with cold air, strangers moving into her house,a man in her room writing a poem, the moon drifting into it,

a woman strolling under its trees, thinking of death,

thinking of him thinking of her, and the wind rising

and taking the moon and leaving the paper dark.

Like Van Allen’s poem, “The Prediction” starts with the moon, which looks down on the world it reflects like the poet looking down on the world he’s created—or perhaps on the world he’s reflecting.

In either case, that moon (again as in Van Allen’s poem) moves under the boughs of trees as if those boughs aren’t there. It illuminates a woman who realizes that she’s in a poem. Her existence isn’t real; she is predicting, not the future, but her present, which is the poem itself (“The Prediction”). When she recognizes she is just a thought, she also recognizes her own mortality (“thinking of death”) and the mortality of her loved ones. The world dissolves around her, “leaving the paper [which is her world] dark.”

Van Allen’s poem isn’t as explicit about its own ephemerality. Strand forthrightly declares that there are no branches. Van Allen merely suggests there are not by suggesting there are. Strand’s poem shouts its own erasure as it vanishes; Van Allen’s whispers, so you’re not sure you can hear it disappearing.

The difference there is in part a function of form; haiku rarely bellow. But the difference between the two poems is also, maybe, a function of venue.

Mark Strand is a successful writer; “The Prediction” is a famous poem. So is the haiku by Kobayashi Issa. Both of these poems about the transitory, fictive nature of reality have managed to defy the transitoriness and, at least to some degree, the fictiveness by becoming historical objects in themselves. The world may be dew, but Issa’s name has a much longer halflife than dew. Life may just be a scribble on a page, quicky erased, but Strand’s words are still around, and that woman strolling under the trees is still there, strolling, whenever we read Strand’s poem. Fame grants a kind of immortality at odds with Strand’s prediction and Issa’s evaporation.

Steve Van Allen’s poem, though, seems unlikely to attain that kind of persistence. Five Fleas is a fun venue in part because it’s so impermanent. Editor Roberta Beach Jacobson accepts rolling submissions, and then posts a hunk of short poems she receives once (or sometimes even twice) a day. You can read through the offerings in a couple minutes, and then, not too long after, the next post takes its place on the screen.

Five Fleas isn’t meant to present timeless poetry for all time. It’s exuberant and ephemeral, highlighting a momentary flash of beauty, insight, or silliness before moving on. Jacobson doesn’t provide author biographies; everyone is a disembodied name, and if there’s a readership, it’s as tiny as the poems themselves. Someone is speaking and someone is (probably) listening. But those someones are semi-anonymous, few in number, and mostly passing through, like the moon through those branches which are there while you look at them, and then maybe aren’t.

I like “The Prediction” and Issa’s haiku quite a bit. But at least for right now, I feel like their acknowledged greatness and profligate recognition somewhat diminishes their appeal, if not their light. Van Allen’s haiku, in contrast, glows briefly, backlit on the internet, before scrolling into the past, as if it wasn’t there.