The Reptile Less Travelled

On Donald Hall's "Alligator Bride"

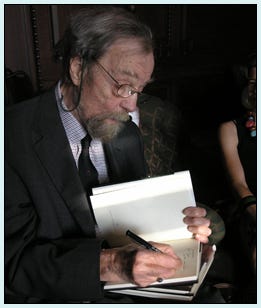

Donald Hall is a poet who writes generally in the bucolic landscape and nostalgic wisdom Robert Frost tradition, fluent in themes of grief and baseball. He’s got a masterful command of rhyme and form, but he’s not especially opaque. Nature is there; nostalgia is here. Together they contemplate the snow falling. You know the drill.

Hall’s poem “The Alligator Bride,” published circa 1969, is different. It starts out more or less as you’d expect; there’s an evocation of time and loss and a twee nod to nature and sentiment.

The clock of my days winds down.

The cat eats sparrows outside my window.

Once, she brought me a small rabbit

which we devoured together…

After that, though, things go decidedly awry. Men start shrieking, a gawdy very un-Hall like gold umbrella shows up, and suddenly we’ve got Alligator Brides and obscure fluids leaking out of our reverie.

The Alligator Bride

The clock of my days winds down.

The cat eats sparrows outside my window.

Once, she brought me a small rabbit

which we devoured together, under

the Empire Table

while the men shrieked

repossessing the gold umbrella.

Now the beard on my clock turns white.

My cat stares into dark corners

missing her gold umbrella.

She is in love

with the Alligator Bride.

Ah, the tiny fine white

teeth! The Bride, propped on her tail

in white lace

stares from the holes

of her eyes. Her stuck-open mouth

laughs at minister and people.

On bare new wood

fourteen tomatoes,

a dozen ears of corn,

six bottles of white wine,

a melon,

a cat,

broccoli

and the Alligator Bride.

The color of bubble gum,

the consistency of petroleum jelly,

wickedness oozes

from the palm of my left hand.

My cat licks it.

I watch the Alligator Bride.

Big houses like shabby boulders

hold themselves tight

in gelatin.

I am unable to daydream.

The sky is a gun aimed at me.

I pull the trigger.

The skull of my promises

leans in a black closet, gapes

with its good mouth

for a teat to suck.

A bird flies back and forth

in my house that is covered by gelatin

and the cat leaps at it

missing. Under the Empire Table

the Alligator Bride

lies in her bridal shroud.

My left hand

leaks on the Chinese carpet.

Was Hall struck in the head? (“The skull of my promises/leans in a black closet”.) Did he get some bad acid in his gelatin? What happened to the friendly white-eyebrowed poet of small towns and byways? What the hell, Don?

When I first read this poem, I thought it might be a sestina—a French verse form of six line stanzas in which the last words of the lines repeat in a set order. It isn’t quite—the stanzas aren’t consistently six lines, and while words repeat (Empire Table, gelatin, the umbrella, the cat) they don’t do so in any set sequence.

The echoes of the form did bring to mind another famously obscure poem of the 60s: John Ashbery’s 1966 “Farm Implements and Rutabagas in a Landscape.”

Ashbery’s a very different poet than Hall. Associated with New York and Paris rather than with New England, his verse is cosmopolitan, witty, queer and deliberately, loquaciously elusive. “Farm Implements and Rutabagas in a Landscape” is a sestina about Popeye the Sailor Man experiencing an obscure rural crisis.

Farm Implements and Rutabagas in a Landscape

The first of the undecoded messages read: “Popeye sits in thunder,

Unthought of. From that shoebox of an apartment,

From livid curtain’s hue, a tangram emerges: a country.”

Meanwhile the Sea Hag was relaxing on a green couch: “How pleasant

To spend one’s vacation en la casa de Popeye,” she scratched

Her cleft chin’s solitary hair. She remembered spinachAnd was going to ask Wimpy if he had bought any spinach.

“M’love,” he intercepted, “the plains are decked out in thunder

Today, and it shall be as you wish.” He scratched

The part of his head under his hat. The apartment

Seemed to grow smaller. “But what if no pleasant

Inspiration plunge us now to the stars? For this is my country.”Suddenly they remembered how it was cheaper in the country.

Wimpy was thoughtfully cutting open a number 2 can of spinach

When the door opened and Swee’pea crept in. “How pleasant!”

But Swee’pea looked morose. A note was pinned to his bib. “Thunder

And tears are unavailing,” it read. “Henceforth shall Popeye’s apartment

Be but remembered space, toxic or salubrious, whole or scratched.”Olive came hurtling through the window; its geraniums scratched

Her long thigh. “I have news!” she gasped. “Popeye, forced as you know to flee the country

One musty gusty evening, by the schemes of his wizened, duplicate father, jealous of the apartment

And all that it contains, myself and spinach

In particular, heaves bolts of loving thunder

At his own astonished becoming, rupturing the pleasantArpeggio of our years. No more shall pleasant

Rays of the sun refresh your sense of growing old, nor the scratched

Tree-trunks and mossy foliage, only immaculate darkness and thunder.”

She grabbed Swee’pea. “I’m taking the brat to the country.”

“But you can’t do that—he hasn’t even finished his spinach,”

Urged the Sea Hag, looking fearfully around at the apartment.But Olive was already out of earshot. Now the apartment

Succumbed to a strange new hush. “Actually it’s quite pleasant

Here,” thought the Sea Hag. “If this is all we need fear from spinach

Then I don’t mind so much. Perhaps we could invite Alice the Goon over”—she scratched

One dug pensively—“but Wimpy is such a country

Bumpkin, always burping like that.” Minute at first, the thunderSoon filled the apartment. It was domestic thunder,

The color of spinach. Popeye chuckled and scratched

His balls: it sure was pleasant to spend a day in the country.

When I first read this in college I was completely baffled because I was trying to follow the plot. But of course there’s no plot, really. It’s an exercise in giggling as you cycle through each of those six words—apartment, thunder, spinach, scratched, pleasant, country—just as various characters cycle into and out of the shoebox apartment.

Ashbery is reproducing the dynamics of a comic strip: the poem is a series of little boxes in which people perform random/amusing manic actions which are conventionally-if-not-logically connected to the next little box of action.

Besides being a goof on the comics page, though, the poem can be read as a goof on the kind of poetry of rural place in the Robert Frost/Donald Hall tradition. Elegaic evocations of wordy gestures (“Henceforth shall Popeye’s apartment /Be but remembered space, toxic or salubrious, whole or scratched”) fly out the window to dead end in the slow confusion of country bumpkins, or in a combination of scatology and mundanity. (“Popeye chuckled and scratched/His balls: it sure was pleasant to spend a day in the country.”) The poem promises a rustic idyll, and instead you get a jumble of more or less invidious tropes about rural folks smuggled into the crowded comic bustle by way of spinach.

Hall knew Ashbery personally, and had certainly read his work. It’s possible that the “Alligator Bride” was a response of sorts if not to this poem exactly, then to the New York school of poetry, with its juxtaposition of odd images and its attention to the cacophony of different levels of language.

In terms of approach, there are two major differences between “Alligator Bride” and “Farm Implements…” The first is that Hall is more sincere—or maybe more accurately, his moments of ventriloquizing sincerity are much more convincing. Ashbery’s praise of country life is always seen through a window tinted with irony. Hall, though, sounds like he’s in one of his other poems appreciating the world’s intensity for entire stanzas at a time before some unaccountable goofiness slithers in on alligator claws.

On bare new wood

fourteen tomatoes,

a dozen ears of corn,

six bottles of white wine,

a melon,

a cat,

broccoli

and the Alligator Bride.

The other contrast with Ashbery is that Hall’s poem is more personal. There’s no “I” in “Farm Implements….” Ashbery’s outside the action, like a man reading the funny pages. But Hall’s right there, oozing into the paper, or watching it ooze out at him.

Big houses like shabby boulders

hold themselves tight

in gelatin.

I am unable to daydream.

The sky is a gun aimed at me.

I pull the trigger.

The skull of my promises

leans in a black closet, gapes

with its good mouth

for a teat to suck.

The big houses like boulders are almost naturalistic; you can imagine Hall looking from his yard at the houses around him, perhaps musing on the distance from his neighbors a la Robert Frost’s “Mending Wall” (“And spills the upper boulders in the sun”). But then some ichorous other slides in, interrupting the usual Hallian “daydream.” The next image is of the universe blowing Hall up, his identity stuffed into a “black closet,” sucking on weird Freudian infantilization.

The two creatures in the poem that aren’t Hall—the cat and the Alligator Bride—look at each other across this stylistic divide. The cat, which is Hall’s, is a natural creature of the outdoors, of sentiment, of memory. The Alligator Bride, though, waltzes in from outside the poem or the self. Is she a figurine of some kind? Is she alive? A symbol? The Bride is vaguely sinister, vaguely satirical, like she’s mocking the poem she’s in, or the poet and his ministerial pieties.

Ah, the tiny fine white

teeth! The Bride, propped on her tail

in white lace

stares from the holes

of her eyes. Her stuck-open mouth

laughs at minister and people.

If the cat is Hall and the Bride is some poet like Ashbery, it seems important that the first is fascinated by and “in love/with” the second. The image of self-dissolution in the closet is disturbing and somewhat dark, but there’s also an attraction there—as if Hall got tired of being Hall and is yearning for more teeth in his poems. A hand leaking wickedness could be about self-loathing, but it also feels like Hall reveling in the unusual ugliness coming out of him, like a child proud of making a particularly vivid mess.

A bird flies back and forth

in my house that is covered by gelatin

and the cat leaps at it

missing. Under the Empire Table

the Alligator Bride

lies in her bridal shroud.

My left hand

leaks on the Chinese carpet.

The cat there jumps at something like Hall’s usual meaning and metaphor, but is distracted by gelatin, which catches it and prevents it from scampering to the end of the poem. The Alligator Bride gets the last word, lying not by Hall’s brain or mouth, but by that expressive left hand, which seems to emit without his will or effort.

The prosody is also gelatined between back and forth; it’s plainspoken and even but unable to settle into a set form. That first line of the last stanza is three iambs, the bird swooping to a traditional rhythm. But the second breaks into quasi anapests, and after the gluey discharge pours out it’s difficult to find any regular rhythm, though it feels like one is always on the verge of breaking through, just as it feels like the poem just about has to mean something and then doesn’t. The poem itself feels like it’s “The color of bubble gum,/the consistency of petroleum jelly,” with lines that sound lovely (the assonance and consonance in “color” “bubble” “gum”, the multi-syllabic roll to internal rhyme of “consistency of petroleum jelly”) but which end up evoking the bizarre or the wicked.

That bizarre and wicked really doesn’t have to be Ashbery. There are echoes here of Wallace Stevens’ “Sunday Morning” too, with Hall’s cat replacing Stevens’ cockatoo on the rug. And that skull of promises in the black closet reminds me of W.S. Merwin’s ominously heavy surrealism. Hall may or may not be referencing something in particular, but whether or no, he seems to be channeling something other, fascinated, like the cat, with a different reptile or plastic self. Hall’s from a tradition of lyric I, which is why his play with lyric not-I here is so startling and strange. For a moment, he’s gotten married to something else. Like that distractable cat, his eye is caught like gelatin, and for a moment he loves the Alligator Bride.

__

This ran on my patreon some years back; thought people might enjoy a poetry break from the ongoing misery…

There is a volume of collected essays, interview transcripts and notes from Donald Hall entitled “Goatfoot, Milktongue, Twinbird” and in an interview with Scott Chisholm, Hall discusses some of his thoughts about “The Alligator Bride”. In this collection of notes/essays he also discusses the visceral underpinnings of poetry, as he experiences them. It is well worth reading. Thank you for this thoughtful essay.

Whoa.

Lost me with these guyz…