THE WILD ROBOT Is Not Wild

You can’t celebrate weirdness by embracing convention.

The animated film The Wild Robot starts out as a charming story about found family and the beauty of embracing your weirdness—and, just as importantly, your child’s weirdness. But then it realizes that its message of idiosyncratic joy is at odds with its mainstream smarm marketing goals. So it panics, and tries to turn itself into a succession of altogether different and less interesting movies. The result is an object lesson in the dangers of being untrue to yourself, though not exactly in the way that director Chris Sanders intended.

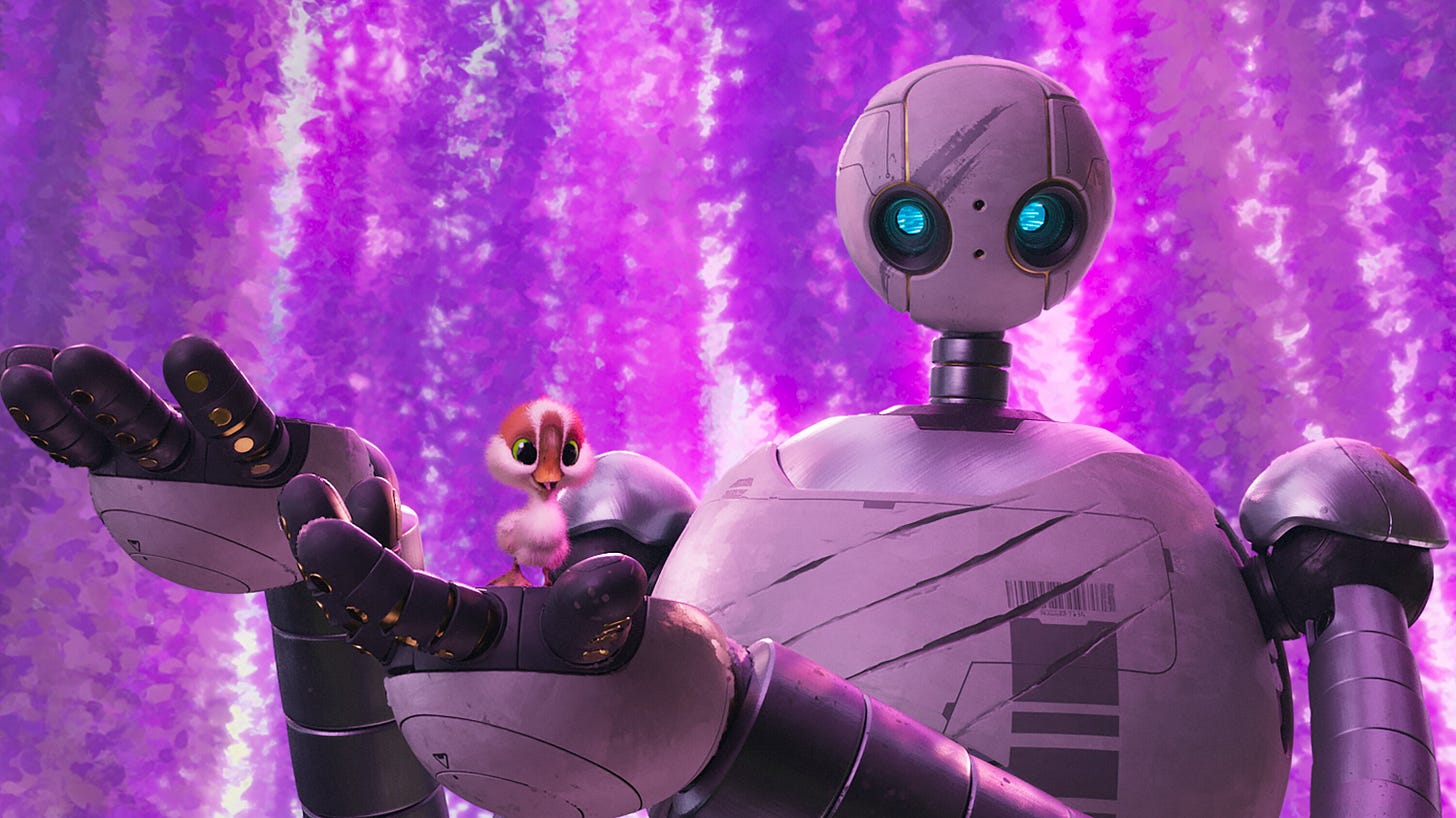

The movie begins with a robot, Roz (Lupita Nyong’o), unexpectedly crash-self-delivering on a remote island chock full of wildlife. After numerous more or less violent misadventures with bears, raccoons, and other critters, Roz accidentally destroys a goose nest, except for a lone egg with the runt of the hatch, Brightbill (Kit Connor). Roz decides to give herself the task of raising the gosling as her own, helped out by a food-motivated fox named Fink (Pedro Pascal.)

The initial scenes of Roz trying to figure out motherhood as Brightbill hops after her trying to imitate her natterings about programs and protocols and transmitters is thoroughly adorable. A conversation with a possum about how no one in fact has the correct programming for raising kids is poignant and even wise. This family seems ready to stagger off down its own path sans clue or map, which is how most families function (or don’t.)

But then we jump to the turn of the season, when Brightbill is an eager, bizarre adolescent goose who thinks he’s a robot, and everything collapses with a whimper rather than a bang.

Brightbill is catastrophically awkward—he’s small, can’t swim, and like Roz, he introduces himself by running through greetings in every language, often babblin self-referentially about his communication protocols. He’s a glaring metaphor for autistic, disabled, queer, or otherwise nonconforming kids, and the other geese bully him much the way that nonconforming kids always get bullied.

The movie presents the bullying as bad. But it’s committed to a straightforward empowerment narrative; Brightbill needs to overcome his oddity and become a Goose among Geese. The weirdo motley non normative family we start with is not good enough in itself; the movie wants a typical heroic arc. That means that Brightbill and Roz have to be validated not on their own terms, but by the very people who reject and bully them. A movie about how outsiders can find each other, love each other, and build community becomes a movie about how those outsiders are only valid if they convince MAGA to anoint them king of the waterfowl.

Sanders as director seems to realize, at least dimly, that his small heartwarming story about small oddballs creating community has gone off the rails. So he tries to salvage it by cobbling together a series of less and less effective plots. Instead of watching Roz and Fink raise Brightbill, the movie turns into a story about Brightbill getting adopted by the good goose leader and taught to lead the flight. Then when that dead ends, other robots show up to try to capture Roz, expending huge amounts of resources and effort in the name of it’s never clear precisely what other than a big blowout ending where Roz gets to do conventional hero things.

What’s the alternative here? Well, there are stories, in various genres, where characters don’t follow the conventional plot path laid out for them.

Vajra Chandrasekera’s Saint of Bright Doors, for example, is about a hero who refuses his heroic fate and ends up wandering through a disconnected sf/f landscape. He’s not exactly thrilled to be cut adrift, but he enjoys the autonomy of not having his destiny stapled to him like an unforgiving shadow.

Jeff Vandermeer’s Annihilation features a character whose most intense emotional attachment is to the swampy ecosystem that develops in an abandoned pool. Throughout the subsequent series, she becomes more and more herself, which is to say she becomes odder and odder, more and more disconnected from the expectations of heroism and even of humanity.

Is that empowerment? Is it heroism? It’s unclear, but as a neurodivergent oddball myself, I appreciated Vandermeer’s refusal to provide conventional narrative closure for his very unconventional heroine. (The movie version, to no one’s surprise, gives her a much more predictable story arc.)

Of course, an animated kids’ feature with a mass audience in mind is not going to pursue this kind of literary weirdness. But that’s the point. Sanders’ story is one about defying convention, but for reasons of genre, capital, and audience, he can’t. And so we get this mess of a movie, which claims that it’s wild even as it follows its rigid programming to its lackluster and inevitable end.

This review is such a good model of how to articulate and follow the arc and sub-arcs of a wide range of movies. As usual, I feel informed and am left inspired to think more deeply about other topics.

Thanks.