What Science-Fiction Books Should Kids Read First?

Whatever they want.

This week science-fiction author John Scalzi posted an irritated post complaining that SF recommendations for kids often focus on books that are 70 years old, rather than on recent releases.

I get Scalzi’s irritation. And also, I think his irritation is maybe a little misplaced. So—because writing about our descent into fascism all day everyday depresses me, and because I think there are some interesting issues here about canons, young people, science-fiction, and books, I thought I’d talk a bit about why Scalzi’s post resonates for me, and why it also doesn’t.

—

This is an example of a post no one else would let me write. If you find my writing valuable/entertaining/worthwhile, and would like me to continue to be able to scribble posts such as this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. I’m having a sale now; it’s 40% off, $30/year.

Fuck those old books

As Scalzi discusses in various threads, the science-fiction canon has an exacerbated, nearly terminal case of the white male canon disease that affects all culture.

The pulp authors who define SF for many older fans—Asimov, Clarke, Heinlein, Bradbury, Campbell—are virtually all white guys with terrible politics whose books are just not that good. You can certainly argue that Faulkner, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, etc. are overrated, or that they have aged poorly in various ways. But I think they do tend to continue to have something to offer; you can at least see why people used to (and still do) think they were important or worthwhile. But with the SF pulp canon, the prose is eh, the thematic material is mostly eh; there’s just no real reason to read them, and a whole lot of reasons (like, Heinlein’s female characters, or Asimov’s history of sexual harassment) not to.

In that context, a call to read newer authors is specifically a call to dump the old mediocre sexist and racist white guys and to instead read around in a genre that has become home to a lot of brilliant writers who are not sexist or racist or mediocre white guys—N.K. Jemisin, Mat Johnson, Catherynne Valente, Martha Wells, Maria Ying, John Chu, Jeff Vandermeer, to just list some of my favorites who happen to be top of mind. Even, for that matter, John Scalzi!

If you are going to recommend books to young people, why not recommend books that are more recent, more likely to be relevant, less likely to be bigoted, and which are just better written? Forget that old crap! Recommend new crap, and give money to authors who are alive and can appreciate it!

Hey! There are good old books!

The thing is, though, that while I’m happy consigning Asimov and Heinlein to the robo-dustbin of history, there are other old science-fiction books that seem less dustbin-worthy. I know that my own daughter read and was passionate about a lot of old books—Ursula K Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis and Parable series, Terry Pratchett’s Mort, Philip K. Dick, H.P. Lovecraft. Most of those were published in the 60s, 70s and 80s—decades before the millennium cut-off that Scalzi is talking about. Lovecraft’s work is from the early 20th century.

One thing that you may have noticed about some of these writers is that they are not necessarily white guys. It’s true that prejudice made it hard for people who weren’t white men to break into science-fiction, as it was difficult for them to break into all fields. But Le Guin, Butler, Joanna Russ, Samuel Delany, and others did in fact exist, and it’s important, I think, to remember that they exist. One way to resist the old white male canon is to vouch for the worth of current writing. But another equally important way to question the canon is to remember and de-erase people like Octavia Butler, who was largely ignored while she was writing, but who today (thorough that process of resistance and recovery) is generally considered one of the most influential and crucial American writers of the 70s and 80s, bar genre.

Lovecraft is a different case. He was a white man, and he was extremely, horrifically, viciously racist in ways that permeate and define his work. Yet, he’s also one of the most generative forefathers of modern horror and sf. Again, just off the top of my head, he’s been a major influence on N.K. Jemisin, Victor Lavelle, Stephen King, Grant Morrison, Matt Ruff, Ruthanna Emrys, Premee Mohamed, Jeff Vandermeer.

Some of these creators play with Lovecraft’s world and ideas as straightforward tribute; others directly or implicitly critique his racism (and sexism). But however he’s used, he’s used a lot. If you had a young SF fan and wanted to introduce them to some foundational works in the genre, in terms of quality and actual contemporary influence, Lovecraft would be a lot more relevant than Heinlein or Asimov, I’d argue.

Kids like different stuff

So, if you’re a parent looking to recommend great SF to your precocious young reader, you should hand them Lovecraft? Is that the takeaway here?

Well, no. Lots of kids (like my daughter!) do in fact like Lovecraft. Lots of kids (like my daughter!) like Octavia Butler. Lots of kids (not mine, but I’m sure they’re out there) like Martha Wells’ Murderbot. Lots of kids would like Nnedi Okorafor’s wonderful Binti. Some kids might well like Heinlein, god help them. And some kids won’t like any of those, and might not even like SF at all. Some of them probably don’t like to read.

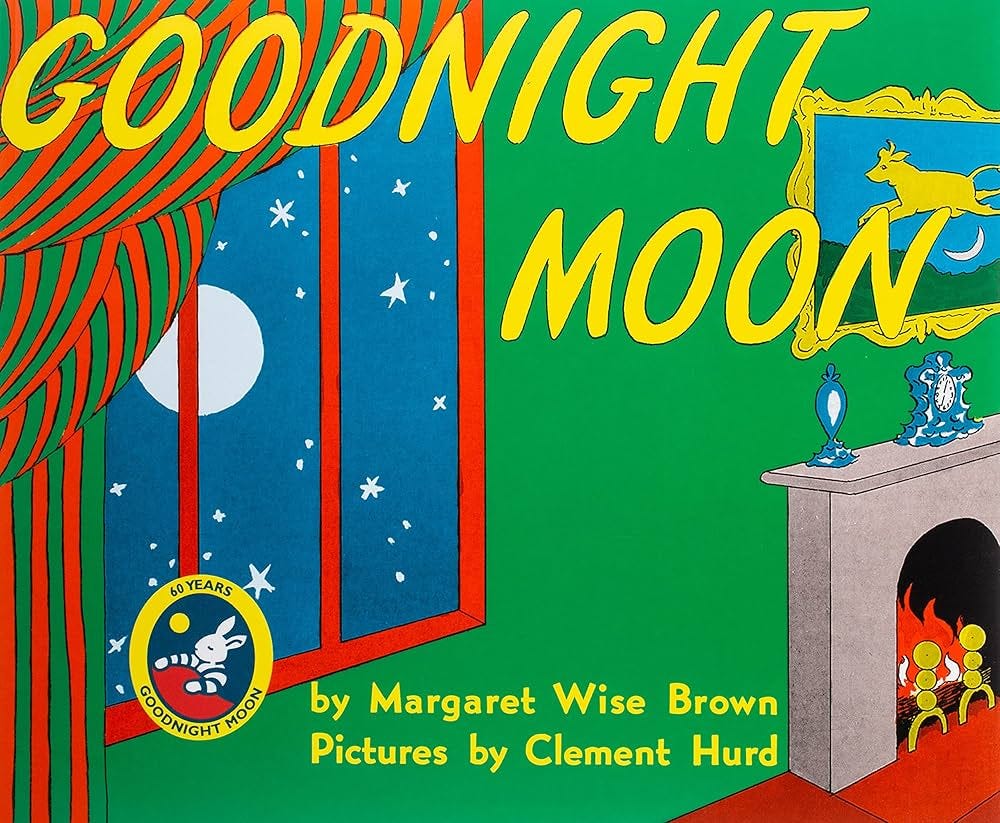

The thing about kids that kind of gets forgotten in these discussions about recommendations and canons is that children are people. That means that they’re individuals; they’re all different. Just like you wouldn’t expect to be able to recommend one book (or one genre!) to everyone, regardless of interests and preferences, so there’s no one right thing to recommend to any one child. Yes, older books can sometimes be more challenging and kids might find contemporary books more relevant. Yes, there are tried and true classic perennial favorites that still resonate. (Lots of toddlers love Goodnight Moon and Dr. Seuss!) Rules of thumb can help, but also these rules of thumb often contradict each other. Books, like people, can be baffling.

The canon is what your friends say it is

One further bafflement that’s worth discussing is that people—young or otherwise—often like things, or want to read things, because other people are reading them. Art, including reading, is a social thing, and people like to engage with art that their friends and acquaintances are talking about or thinking about.

My daughter read the Harry Potter books and the (dreadful) Ranger’s Apprentice series largely because her friends in middle school were reading them and excited about them. Now that she’s reading Nabokov and Kafka (in the original German), and now that J.K. Rowling has turned into the leader of an international hate movement, I think she looks back on those passions with a certain embarrassment. But who among us hasn’t read something mediocre because friends recommended it?

When kids want to read what their friends are reading, that does often mean more contemporary books—the last Ranger’s Apprentice book so far came out in 2019. On the other paw, though, kids often also interact with, talk to, and take cues from their parents—which means that at least sometimes they might read something—like, say, Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, Miller/Sienkiewitz’s Elektra Assassin—because you as their parent say, “Hey, this is awesome.” And sometimes, you might read something because your kid loves it. That’s how I ended up reading Ernst Kantorowicz’s The King’s Two Bodies, which my daughter was obsessed with when she was a high school freshman.

My daughter’s obsession with a classic historical study of medieval politico-theology demonstrates that my daughter was an odd child. But all children, like all people, are odd in their way. The best rule for reading and recommendations is to not have rules or canons. You know your child; point them to something you love that they might love. And if they hate a book you recommend, well, learning what you dislike and why is part of being a reader too.

The first sci-fi book I ever read was Madeline L’Engle’s “A Wrinkle in Time” and it got me hooked on the genre throughout my teens. I happen to love Ray Bradbury and I still own a huge anthology of his short stories that I go back and read from time to time. “The Small Assassin” and “The Veldt” are two standouts that still give me the shivers after all these years. For older teens, I’d recommend Margaret Atwood’s “Oryx and Crake”. The three original Dune books are also very good. And for YA readers, John Christopher’s Tripod series. And what about “Brave New World” or “A Clockwork Orange”? Or “Ender’s Game”? Those are great!

Not sci-fi, but I read “The Once and Future King” by T.H. White when I was about 14 or 15 and it still in my top favorite novels list all these years later. And if you prefer a female POV on Arthurian legend, “The Mists of Avalon” is also wonderful.

I'm 73, out of high school in 1970, but in high school an enlightened librarian steered me to 3 books I'll never forget, all involving prejudice in one manner or another. I was in Florida, our high school had been integrated only since 1967, and I was steered to Asimov's "Pebble in the Sky", which taught me that the middle galaxy people were not better than those from the outskirts. She also "forced" me to read Pat Frank's "Alas, Babylon", dealing with racism and the Cold War which became hot in that book. Black and white had to live together because there weren't enough of either left to form a society. I also remember Clifford Simak's "Way Station" which dealt with prejudice against those with one form of mental illness. I will say that all three shaped my worldview. Yes, they were written back in the dark ages, but they all have a valuable lesson to teach us today.