When George Bailey Looks In the Mirror, Does He See Patrick Bateman?

Who is the man in the skinsuit?

Every Christmas, we all turn on the television to watch the beloved classic about a man who, face to face with the ruinous cruelty of capitalism, loses his own sense of self before a good angel reassures him of his essential innocence.

I’m speaking, of course, of American Psycho.

And, sure, of It’s a Wonderful Life too. The two films are both set partially at Christmas, but otherwise seem like they have little in common. The 1946 Frank Capra movie is a warm, sincere celebration of small-town Americana. Marry Harron’s American Psycho, from 2000, is a vicious satirical sneer at the corporate rat race. They’re mirror images. Except that both of them are about the mirror self who isn’t there, and the emptiness under the skin suit of the successful man.

In one of the first scenes in American Psycho, wealthy smug corporate jerk Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) drones on about his extensive body wash regimen, concluding with a face mask treatment. As he pulls off the mask, revealing the face under his face, he looks in the mirror and his voiceover explains deadpan, “There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me…. I simply am not there.”

Sure enough in the rest of the film we learn that Bateman is not who he appears—and even that he may essentially be no one at all. He has a fiancée and a high-powered corporate job. But he doesn’t seem to care about the first and hardly seems to work at the latter.

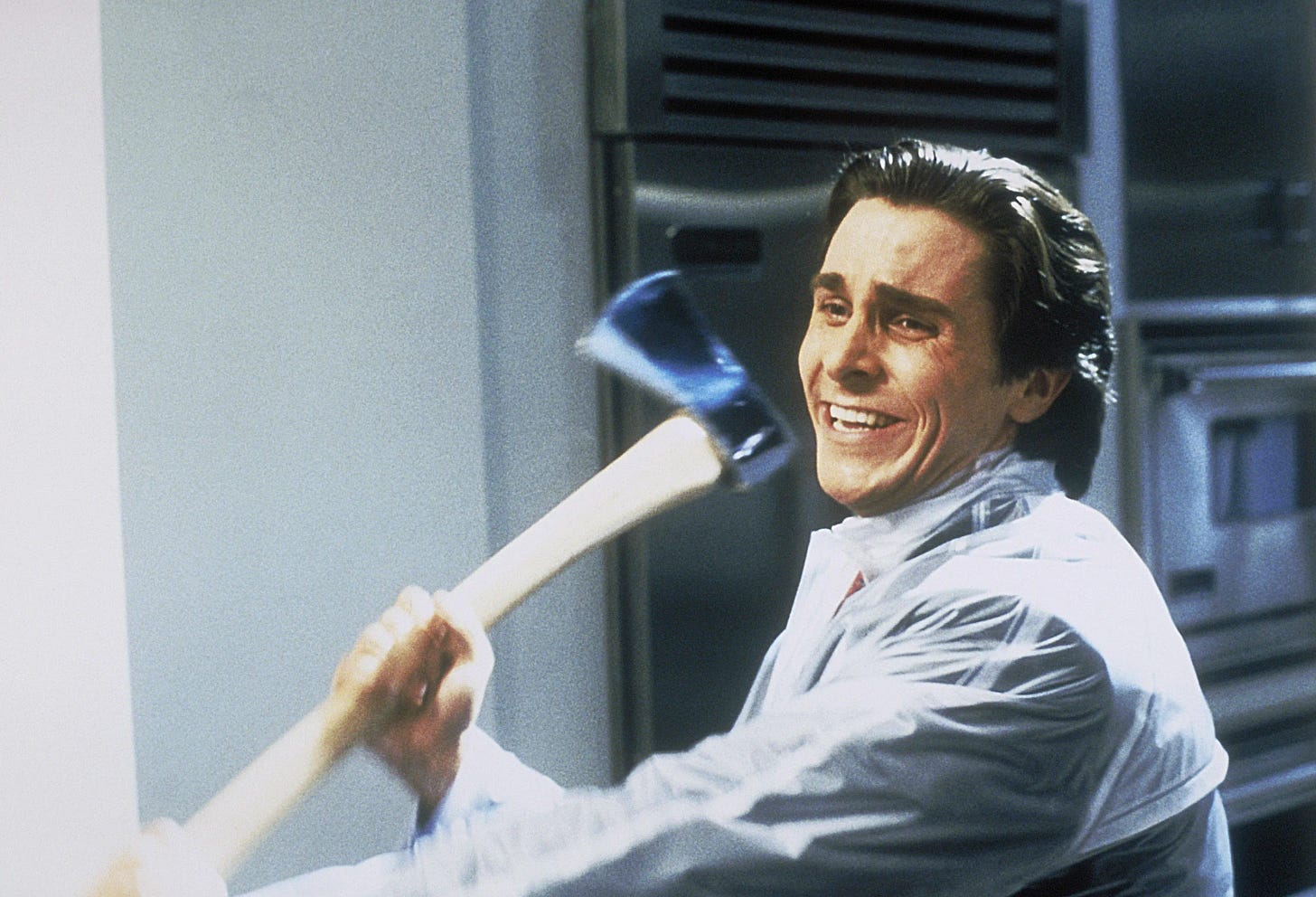

Bateman does have a passion for status symbols; he wants the right wine, the right apartment, the right reservation at the right restaurant. But that’s less because of greed than out of a manic rage for fitting in— also expressed in his bizarre fascination with the minutia of bland 80s pop. He turns on Huey Lewis’ “Hip to Be Square” and then axe-murders a colleague who has a better business card. Bateman doesn’t fit into the perfect square corporate image and can’t tailor himself to fit. So he tailors other people. With a sharp edge.

George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart) in It’s a Wonderful Life seems like a much less bitter and disturbing character. But the parallels with American Psycho make you wonder. Like Bateman, Bailey is driven by ambition; he wants to get out of the little town of Bedford Falls, see the world, and be a success. Instead, he gets stuck running a small nowhere bank, and eventually faces financial ruin.

At which point, the kind, compassionate George who does everything right pulls off his outer-layer and starts to reveal another self. Jimmy Stewart can melt down like few other actors can melt down, and his vengeful, rage-filled, explosive, haunted and cadaverous ill-shaven George, is so convincing you wonder if the George who’s everyone’s friend wasn’t exactly as much of a lie as normal Patrick. “George, why must you torture the children!” his wife demands, which could certainly be read to mean that this is not a one-time tantrum. Maybe, off-screen, he’s tortured the children before.

You can see Patrick’s violence in George. You can also see Patrick’s emptiness. When George is about to kill himself, an angel appears and tries to persuade him to live by showing him how badly off Bedford Falls would be without him.

The dream sequence is supposed to testify to George’s goodness. But with a little cynicism, it could also be read as Bateman-like wish-fulfillment narcissism. George’s deepest wish is to see that his wife would have found no man without him. He wants to believe that Bedford Falls would descend into iniquity, ruin and (for some reason) jazz clubs if George hadn’t been there to fight evil banker Mr. Potter.

Patrick Bateman at the end of American Psycho realizes he may have not murdered anyone after all and is almost disappointed. He imagined himself as a great force for evil. George imagines himself as a great force for good. Obviously there’s a distinction there. But there’s also some parallels.

Other characters in American Psycho keep mistaking Bateman for other corporate drones; part of the reason he escapes culpability for his crimes (if they occurred) is that no one can remember who he is. He’s eminently replaceable—and George Bailey’s greatest fear is that he too has made no mark on the world.

Bateman and Bailey embody a bleak capitalist masculinity. Both have two selves: the success they want to be and the failure they are. The failure is nobody; it’s a blank. But the success is also nobody, since it’s illusory and unreal. Split into two absences, they both disappear. In the place of a person, there is only rage and emptiness.

It’s A Wonderful Life suggests that that doesn’t have to be the last word. In the spirit of Christmas giving, George’s community comes together to save him. He is somebody after all. Specifically, he is his relationships to other people. Those are relationships which Bateman noticeably lacks; he’s as alienated at the Christmas party as he is everywhere else. George is saved by his great love for his wife. Bateman casually breaks up with his fiancée because, he says, he just doesn’t care about her that much.

Bailey is a better man than Bateman. But once you’ve glimpsed the Bateman peeking out from the Bailey, it’s hard to unsee. Bateman isn’t sure what’s real at the end of his film. Are we sure Bailey knows truth from delusion at the end of his? George’s corny happy ending shows it’s hip to be square. That could be George becoming a better man. Or it could be that he’s just readjusting the mask.

I always thought ‘what a sappy way to cash out the fantasy of non-existence.’ Yes, it’s narcissistic. Still, it seems we inevitably do have to believe the world is better with us in it, even though it is probably not the case. The value of what we do is contingent on our being there but WE value it. If one’s children did not exist, then some other children might. They would matter just as much. But one has to believe one’s children matter in some absolute and cosmic way. So I do like your interpretation. Somebody should re-do this movie where he discovers he can just NOT EXIST and it’s FINE.

Hah! This is hilarious. But George doesn’t imagine himself as a great force for good. I always saw ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ as being about a guy who is a fuck up and just blundering along but he has a nice life, and then, terrified his fuck ups have finally caught up to him, he considers suicide. But it turns out the individual is not so important. You are a nobody AND a fuck-up and it’s possibly OK because maybe you do little things that aren’t so significant but they can add up. Which is perhaps not true! But a good thing to believe if you are considering suicide.