Why Did W.E.B. Du Bois’ Support Zionism and Stalinism?

A lifelong struggle with elite vanguardism.

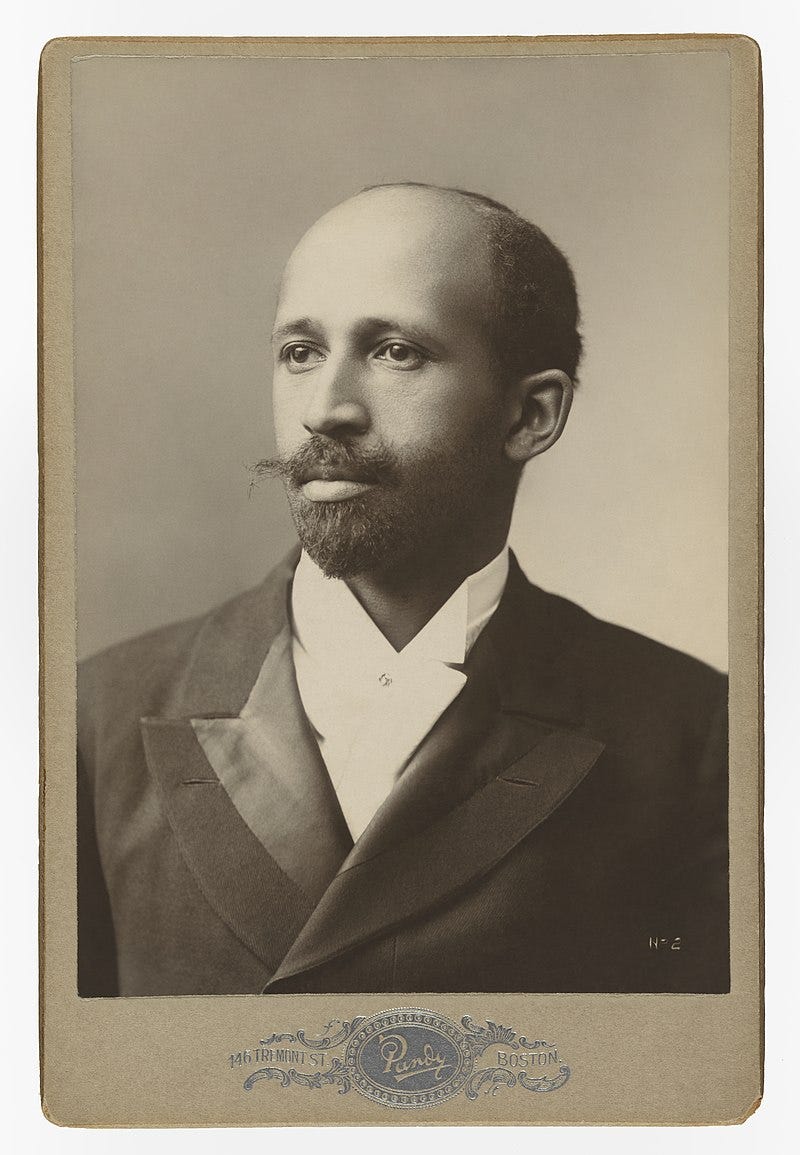

W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) has a good claim on being the most important American intellectual of the last couple of hundred years. He was a pioneering historian, philosopher, antiracist, and anti-imperialist, who, despite racist lack of recognition from peers and active hostility from US authorities, fought white supremacist and colonial ideology throughout his long life.

And yet, over the course of that life, Du Bois also lent his support to a number of very ugly causes and ideas. His support for Stalin is relatively well-known. But (as this essay will discuss) it wasn’t exactly an aberration. He turned a blind eye to numerous atrocities, and not only to those committed by Communists.

How can we reconcile Du Bois’ fight for equality and freedom with his repeated enthusiasm for oppressive, cruel, and even genocidal regimes and causes? How could someone so clear-eyed about the costs and evils of inequity lend his prestige in so many instances to brutality and repression?

I don’t have definitive answers to those questions. But I think it’s worth walking through Du Bois’ inconsistencies if only to show that he was, in fact, inconsistent. His greatest insights, I think, contradict his worst moments. In that sense, his career can be seen as a long struggle with what we might call elite progressivism—the idea that certain groups are benighted and that the cause of racial transformation and uplift must be imposed, top down, by those chosen as the vanguard of history.

—

No publication would ever have commissioned an essay like this. So, if you enjoy my work, and would like me to continue writing ambitious pieces in this vein, consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s $5/month, $50/year

—

Du Bois and bottom up resistance in the Civil War

Du Bois was responsible for so many key insights in so many fields it’s difficult to choose any one of his interventions as the most important. But if you forced to pick one defining intellectual legacy, a strong argument could be made for his revolutionary (in various senses) interpretation of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

In the early 20th century, white historians of the Dunning School (like the execrable Woodrow Wilson) interpreted the Civil War and its aftermath as a failed experiment in multiracial democracy. According to the Dunning School, the North freed Black people out of an excess of nobility during the war.

After the war, in the Reconstruction period, Black people were enfranchised and were able to participate in voting and government as never before. The Dunning school argued that this participation was a disaster, and that multi-racial Reconstruction governments were hopelessly corrupt. In this interpretation, the KKK white surpremacists were a group of civic-minded heroes who used extra-judicial violence to overthrow unjust regimes and restore good (white) governance to all (white) people. (This narrative was the inspiration for the infamous film Birth of a Nation.)

In his groundbreaking 1935 book Black Reconstruction in America, Du Bois completely upended this argument. With meticulous scholarship, he showed that Reconstruction governments were not corrupt, but instead made important efforts to advance public health and public education initiatives which benefited both newly freed Black people and poor whites. The Reconstruction governments collapsed not because of their own failures, but because of sustained racist violence—and because most white working class Southerners chose racist solidarity over class interests.

Just as important as Du Bois’ reinterpretation of Reconstruction governments was the way he challenged the received wisdom about who saved who during the Civil War. Again, white historians generally presented enslaved Black people as beneficiaries of white Northern largesse. Du Bois, though, showed that as the war progressed, enslaved Black workers engaged in a general strike. They refused to labor on plantations, and attempted en masse, and with a good deal of success, to escape to the North.

This widespread act of resistance caused an economic crisis in the Confederacy, coupled to an ideological crisis, as white people, North and South, were forced to confront the fact that, despite nationwide propaganda, Black people were not in fact happy in slavery. In this sense, the North did not win the war and end slavery. Rather, Black people themselves ended slavery as an economic and ideological force, giving the North the power to win the war.

Du Bois realized, as other white historians had not, that enslaved Black people themselves—the most oppressed and the most exploited—were the drivers of radical change during the Civil War. The Dunning School interpretation was not just racist, but an exercise in condescending elitism. Dunning historians believed that only a more educated, higher social stratum could impose progressive measures—ending slavery, ending corruption, imposing ordered hierarchy.

In contrast, Du Bois rejected the Dunning School’s argument that history is made, and justice advanced, primarily by an elite vanguard. In fact, the elite vanguard of white militias and their white historian apologists were simply thugs, racists, and propagandists, who claimed to be the forces of the future in order to impose reactionary terror. Black Reconstruction in America is a brilliant statement of faith in the agency, insight, and struggles of ordinary people, who Du Bois champions against their brutal and brutalizing “betters.”

Du Bois and the Talented Tenth

Du Bois saw through the cruel white supremacist snobbery of the Dunning School historians. However, he was not always immune to elitism. In fact, his most important early essay was a 1903 argument for a “Talented Tenth”—a group of educated Black men who would lead the rest of the race to uplift.

Or as Du Bois put it:

The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men. The problem of education, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth; it is the problem of developing the Best of this race that they may guide the Mass away from the contamination and death of the Worst, in their own and other races.

Du Bois in his essay was directly responding to Booker T. Washington, who argued that post-Reconstruction Black people should focus on industrial training. Liberal arts education, Washington believed, was a waste of time for Black students, as well as a potential provocation to whites.

Du Bois countered by arguing that higher education and learning were vital for racial progress and equality. Washington was advocating for sustained racist hierarchy; Black people, in his view, should resign themselves to working class jobs and working class aspirations within an entrenched white supremacist system. Du Bois rejected that approach as defeatist and insulting. Education should be available to all. And “all” definitely included Black people.

But while Du Bois rejected Washington’s racist hierarchy, he simultaneously embraced a naturalized elitist meritocracy. “The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men,” he said. And added that the problem for Black people was to develop “the Best of this race that they may guide the Mass away from the contamination and death of the Worst.”

Du Bois is arguing, with few qualifiers, that educated, intelligent Black people are better than the less educated, and that less educated Black people are actually a source of “contamination.” Du Bois does not acknowledge that access to education—especially in a violently racialized and oppressed population—is going to be radically uneven. Nor does he think about the way that knowledge and power can be seductive and deradicalizing (as it was, for example, for Booker T. Washington.)

Du Bois, as he embraced radical politics, repudiated the idea of the Talented Tenth. In 1948, he pointed out that an elite vanguard may care only for itself, rather than for the people it is supposedly uplifting.

When I came out of college into the world of work, I realized that it was quite possible that my plan of training a talented tenth might put in control and power, a group of selfish, self-indulgent, well-to-do men, whose basic interest in solving the Negro problem was personal; personal freedom and unhampered enjoyment and use of the world, without any real care, or certainly no arousing care as to what became of the mass of American Negroes, or of the mass of any people.

More, Du Bois implicitly, but firmly, rejected the Talented Tenth in his work on Reconstruction. It was not educated, high minded Black educated men who were primarily responsible for ending slavery. Instead, enslaved Black men and women, mostly with no access to education, freed themselves by bravely daring retribution and death to escape the plantation and cripple the Confederate economy.

With his analysis of Reconstruction and his turn to Marxism, you could argue that Du Bois’ later career was in fact one long repudiaton of a bourgeois progressive ethic. He flirted with the idea of elite vanguardism in his early career, and then rejected it. That’s an inspirational narrative of an intellectual journey towards equality and justice.

Unfortunately, the story is a little more complicated than that.

Du Bois and Imperial Japan

The fact is that while Du Bois repudiated the Talented Tenth, he was attracted to various forms of elite progressive vanguardism throughout his life. After he became a Marxist, the vanguardism was not generally bourgeoise. Instead, it tended to be nationalist—and ethnonationalist.

One of the more painful examples here is Du Bois’ enthusiastic, consistent, and never-reconsidered support for the violent colonial depredations of Imperial Japan.

Du Bois was drawn to Japan because, he said, there was “a certain bond between the colored peoples because of world-wide prejudice.” Du Bois saw rapidly industrializing and modernizing Japan as the champion by default of all non-white people; he cheered on Japan’s victory over Russia in the 1905 Russo-Russian War and hoped that Japan’s successes would lead to a worldwide revolt against white imperialism and racism.

Japan, then, was the progressive, antiracist vanguard, which was—like the Talented Tenth—to lead the mass of less accomplished peoples to freedom. And if those less talented 90% demurred? Well, Du Bois was not sympathetic—as became clear in his statements on China.

Japan in the 30s invaded China, and committed horrific acts of violence against Chinese people and civilians. In 1932, Japan carved out Manchuko, a puppet state of influence in China, which, while ostensibly a republic, was completely controlled by the Japanese.

Du Bois, however, did not condemn Japanese imperialism. Instead, he argued that Japan was “the only strong leader of the yellow people” and that they therefore had a righteous justification in taking the coal, iron, and territory of China and Korea in order to counter and stand against perfidious and racist Europe and America.

China, in Du Bois’ view, should have voluntarily aligned with Japan, but Chinese leaders and people were disunited and, moreover, duped by Europe. ("The Chinese are utterly deceived as to white opinion of the yellow race.”) Japan, as the progressive vanguard, had to seize China for the greater good of civilization—just as, for the Dunning school, the KKK had to overthrow Reconstruction governments for the greater good of civilization.

Du Bois visited Manchuko in 1936, but the experience only led him to double down on his colonial apology. Guided by the Japanese, he concluded that “The people appear happy, and there is no unemployment” and added, shockingly, that Manchuko had convinced him that “colonial enterprise by a colored nation need not imply the caste, exploitation and subjection which it has always implied in the case of white Europe.”

Du Bois in his discussions of Reconstruction emphasized that Black resistance to white plans and designs was not laziness or contrariness, but was a calculated program of defiance. Yet, Du Bois was baffled at China’s reluctance to bow down to Japan.

When the Chinese attempted to leverage European nations against their closer, and therefore more immediately dangerous, neighbor, Du Bois reacted with bafflement and anger. He chastised China for “refusing…to allow [the Japanese] the same economic freedom that China almost eagerly gave to the white man”, and added that China was blocking Japanese modernizing reforms via an “almost impenetrable wall of custom, religion and industry” and “a rock wall of opposition and misunderstanding.”

In Du Bois’ most incendiary comment, he said that China preferred “to be a coolie for England rather than acknowledge the only world leadership that did not mean color caste”—that is, “the leadership of Japan.” Du Bois had, in his own mind, identified the progressive force for the future. Japan was the elite vanguard who would overthrow caste and injustice worldwide. That elite vanguard had the right and the duty to take whatever they needed for their task. If that meant subjugating China, so be it—and if China demurred, that only showed that they were (per Du Bois’ comments in his Talented Tenth essay) a source of “contamination and death,” and needed to be disciplined.

Du Bois, Zionism, and Stalinism

The same longing for an elite vanguard, and the same violent disgust with those who resist said vanguard, can be found in Du Bois’ postwar support for Israel.

As Vaughn Rasberry discusses in his 2016 book Race and the Totalitarian Century, Du Bois was very sympathetic to Jewish colonial ambitions in Palestine.

In his 1948 article, “The Case for the Jews,” Du Bois argues, first of all, that Jewish people have a unique claim to Palestine because “Every child knows that ancient Jewish civilization and religion centered in Palestine.” In contrast, he denigrates Arab rights and claims to the region not because Arabs are (supposed) newcomers, but because Arabs are (supposedly) backwards and anti-modern.

“Among the million Arabs,” Du Bois writes, “there is widespread ignorance, poverty and disease and fanatic belief in the Mohammedan religion, which makes these people suspicious of other peoples and other religions.”

Du Bois concludes that “the question of a land is in the long run the question of the use to which the land is put.” The Jewish people, Du Bois believes have made major contributions to “modern civilization, not only in banking and finance, but in the arts, in the fineness of family life, in the magnificent clearness of…intellect.” Thus it is right that “young and forward-thinking Jews” should be entrusted with “bringing a new civilization into an old land and building up that land out of ignorance disease, and poverty into which it had fallen; and by democratic methods erecting a new and peculiarly fateful modern state.”

When Du Bois turns to Stalinist Russia, the groups and individuals in question are different, but the logic is much the same. One group (Zionists or Stalinists) is at the vanguard of history, and therefore has the right to displace, destroy, and/or rule over those elements that retard progress and modernity. Rasberry quotes Du Bois’ account of a 1936 trip to Russia.

It is October, 1936, I am in Russia. I am here where the world’s greatest experiment in organized life [is being made], whether it fails or not. Nothing since the discovery of America and the French Revolution is of equal importance….Can one question for a moment the gain to civilization if it were proven possible to make human welfare rather than profit the chief end of industry? Even if Russia fails to accomplish this, or accomplishes it only in part, what a stupendous adventure, what a search magnificent, and at a cost so far less than that of any similar revolution in world history, if perchance there ever was such an effort on such a scale.

As Rasberry points out, Du Bois is protesting way, way too much when he claims that the “cost” of Russia’s revolution is “far less” than that of other revolutions. The Stalin-imposed famine in Ukraine is believed to have killed some 4 million people in 1932, four years before Du Bois wrote his apology.

Rasberry also emphasizes that Du Bois, throughout his pro-Stalinist writing, focuses on the right to fail—the idea that the Soviet experiment is unique and important. Western white imperialism had a horrific, terrifying body count, Du Bois argued. Given that wretched history, and given the difficulties the USSR faced due to violent Western attacks, it was reasonable to give Communists ethical leeway in their fight for equality, and not least for racial equality.

The problem is that the “failure” of Stalinism, where it failed, did not result in negative consequences for Stalin. It resulted in the deaths of people with much less power. Or to look at it another way, the failure involved treating people in much the same way as capitalist colonizers treated people—as means rather than ends to be stigmatized and slaughtered in the name of whatever scheme for wealth or power happened to catch the eye of those with the resources and guns.

In Asia, the people to be stigmatized in Du Bois view were the Chinese. In Palestine, it was the Arabs. And in Russia, Du Bois, like Stalin himself, frames the relatively wealthy peasants, or “kulaks”, as the avatars of villainous reactionary capitalism, who must be defeated by the revolutionary vanguard.

“The Kulaks had the mentality of capitalists,” Du Bois argues, “enforced by ignorance and custom. The opportunity to cheat and coerce the poor peasant was broad and continuous. Stalin knew the kulak; his fathers had been their slaves for generations. He did not hesitate. He broke their power by savage attack.”

Again, the stigmatization and arguably the racialization of “kulaks”, which essentially included anyone who objected to Stalin’s policy of collectivization, was used as the ideological justification for a deliberately imposed famine in Ukraine, which killed millions of people and is one of the most horrific genocides in history.

What’s notable for our purposes, though, is the way that Du Bois’ depiction of the kulaks is, once more, consistent with his depiction of the Chinese and of Arabs. In each case, these groups are indicted for ignorance and backwardness. They fail to see or to appreciate the progress of history which Du Bois has identified; they stand in the way of modernization and of progress. They are, in other words, caricatured, racialized, colonized others.

When Du Bois excoriates the (supposedly) debased Chinese, Arabs, and kulaks, he sounds much like the Dunning school historians who excoriated the (supposedly) debased enslaved and emancipated Black people of the South. In one case, Du Bois courageously and brilliantly showed the emptiness of the ideology of the progressive vanguard. In the others, he took that ideology as his own.

Lessons for Progress

Rasberry notes that discussion of Du Bois often “congeals” around a biographical myth of disillusionment and decline.

…the young, idealistic intellectual dedicates his life to the eradication of racism, the attainment of full citizenship for black Americans, and the inclusion of blacks within the wider American society and the progress of modernity in general; throughout his long life the United States and its Western allies fail to make adequate progress on any of these political aims; by the time the nation appears to be rescinding its commitment to de jure segregation, Du Bois comes under increased state surveillance and emerges as a full-fledged casualty of the Cold War; exhausted and disgusted, Du Bois abandons hope in American racial progress and cynically adopts Stalinism before expatriating to Ghana—once his confiscated passport becomes reinstated after six years—at the age of ninety-one.

Rasberry counters this myth by suggesting that Du Bois’ “theory of the global color line comes to light fully in relation to his attachment to the Soviet experiment.” Rather than a narrative that goes from hope to despair, Rasberry suggests that following the course of Du Bois’ chronology leads to fulfillment, or at least to greater understanding, of Du Bois’ life and thought.

Rasberry’s argument is thought-provoking and based in an exhaustive and impressive command of the source material, which I certainly can’t match. I do, though, wonder if there might also be value in seeing Du Bois’ thought in terms of vacillation and circling, rather than as a journey of progress, whether backwards or forwards.

One advantage of refusing the brute logic of the timeline is that so much of Du Bois’ thought is engaged with that very brute logic. The ideologies of colonialism and racism over the last centuries are inextricable from ideologies of progress. Certain peoples, certain nations, certain places, are stuck in the past—or worse, exert a backwards drag on the present. Other peoples, nations, and places are in the vanguard of time, carrying us towards modernity, equality, and perfection.

In this view, the goal of progressives—like Woodrow Wilson, like Stalin, like the Zionists, like the Imperial Japanese—is not to ensure that everyone is equal or that everyone is free. Rather the goal is to seize the reins of history and ride as brutally as necessary over anyone who gets between them and the future. When you’re sitting upon that horse, there is not really a distinction between left and right, nor even between right and wrong. There is only those in the vanguard riding forward, and those beneath the hooves, trying to trip you up.

Du Bois throughout his career saw himself atop the horse, whether as one of the Talented Tenth, as a partisan of an imagined anti-white Japanese empire, as a Stalinist reigning retribution on the kulaks, or as a Zionist brushing aside the intransigent Arabs.

And then, sometimes, in his most visionary moments, he saw what most intellectuals and leaders don’t, which is that emancipation often happens, not because some vanguard has seized history, but because oppressed people take whatever space they are given to embrace what they can of freedom and justice. Du Bois’ work stands as a testament to the power of that insight, and to the difficulty even the best of us have in holding to it.

---

One is astonished in the study of history at the recurrence of the idea that evil must be forgotten, distorted, skimmed over. The difficulty, of course, with this philosophy is that history loses its value as an incentive and example; it paints perfect men and noble nations, but it does not tell the truth.

—W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America

As the son of Stalinists myself, I really appreciate this nuanced consideration of the great W.E.B. Du Bois’s complex — and sometimes contradictory — attitudes toward elitism and the role of vanguards. It is a relief to acknowledge the blind spots of even the most brilliant of our thinkers. The truth can hurt more than an idealization, but (I believe) it allows us the most capacious understanding of what it means to be human.

this is wild and incredibly approachable as someone not super familiar with the existing history. As a disabled person I gotta say it's wild to me how eugenecist these ideas seem, too (eugenics ideology was very present in the US during his life, and integral to much racism). the idea that a group of people, almost or even at a biological level, could be considered to be tainting "progress" with their existence / resistance / etc... or somehow not deserving of autonomy / biologically unqualified to know ~whats good for them~. yeah. I was particularly struck by the contamination comment and the conflation of so considered Best people with a very meritocracy idea of intelligence in that regard and wonder if anyone has written about that possible influence on his ideas as well... idk. this was fascinating and horrifying and very nuanced. well done. I feel like I have just feasted on words.