Why I Don't Like Mary Oliver's "The Swan"

I don't want poetry to keep telling me it's offering me deep poetic truths.

Image: Marek Szczepanek

Given Mary Oliver’s popularity, it’s probably inevitable that her detractors have been labeled elitists. Maggie Smith, for example, argues that Oliver’s critics have an “ugly disdain for poetry that consoles and inspires. Dare I call it snobbery?”

No one wants to be a snob, and I’d like to enjoy Oliver’s poetry, since so many others seem to.

Unfortunately, I don’t. And part of the reason I don’t is that her work doesn’t just set out to console and inspire. She isn’t writing pop music schmaltz such as “I Can’t Make You Love Me” or “I Will Survive.”

Pop music isn’t very pretentious; it tends to speak from a position of common experience or solidarity. We’ve all experienced romantic rejection. We’ve all reacted to that rejection with resignation or defiance or a mix of the two. Songs about that are maybe partially meant to help you find strategies for improvement. But they also just tell you, “We’ve all been there too.”

Oliver’s poems, in contrast, insistently claim a vaguely highbrow, vaguely spiritual insight and oomph. They’re not inspiring or comforting (just) because they offer inspiration and comfort for all. They’re inspiring and comforting, supposedly, because they promise an access to deep poetic truths. If Oliver’s work is sometimes treated with condescension, I think it’s a reflection of an attitude inherent in the poems themselves. It takes a certain lack of humility to present yourself as a humble seeker.

Swan vs. Nightingale

As an example, I’d point to one of Oliver’s most famous and beloved poems,

The Swan

Did you too see it, drifting, all night, on the black river?

Did you see it in the morning, rising into the silvery air –

An armful of white blossoms,

A perfect commotion of silk and linen as it leaned

into the bondage of its wings; a snowbank, a bank of lilies,

Biting the air with its black beak?

Did you hear it, fluting and whistling

A shrill dark music – like the rain pelting the trees – like a waterfall

Knifing down the black ledges?

And did you see it, finally, just under the clouds –

A white cross Streaming across the sky, its feet

Like black leaves, its wings Like the stretching light of the river?

And did you feel it, in your heart, how it pertained to everything?

And have you too finally figured out what beauty is for?

And have you changed your life?

Characteristically for Oliver, “The Swan” enacts and recommends a powerful identification with the natural world. There are thematic echoes of Hopkins’ “The Windover” or Shelley’s “To a Skylark,” as the reader is encouraged to feel themselves lift up and fly with some iconic avian. Oliver’s poem is in a controlled free verse, with copious use of alliteration (“Biting the air with its black beak”), slant and internal rhymes (“Streaming across the sky, its feet”), simile, and metaphor. The lines expand and contract like the bird’s wings beating as the poem tries to capture both the freedom and the formal beauty of the swan on the wing, graceful but unfettered.

The main structural device in the poem is the question mark. Every sentence is an interrogative directed at an interlocutor, the reader. Oliver doesn’t ever use the word “I”; instead the poem uses “you” as a form of collective exhortation. “Did you too see it?” encourages the reader to join the narrator in viewing the swan and ultimately, as the rhetoric heightens, to join her in becoming the swan. “And did you feel it, in your heart, how it pertained to everything?”

This is the iconic romantic poetry move—a triumphant expansion of the self through poetic sensibility, celebrating pantheistic oneness and the human capacity for feeling and imagination. Thus Keats in “To a Nightingale.”

Away! away! for I will fly to thee,

Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards,

But on the viewless wings of Poesy…

Keats’ poem though is aspirational, and therefore conflicted.

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!

No hungry generations tread thee down;

The voice I hear this passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown:

Image: Carlos Delgado CC

Keats is aware that the bird he’s listening to is not in fact the same bird heard in ancient days. The song (or the poem) may be eternal; the individual (or the poet) is not. Keats imagines himself escaping his (dying) self, and becoming one with the nightingale. But he knows that that’s impossible—except in the sense that he and the bird are both mortal, and will one day be united in not-being.

Feeling oneself connected to the natural world expands the self, but also contracts it. Poetry and imagination give Keats a certain relief and hope, but it’s limited. The power of the poem is in the movement between empowerment and failure, the way poetry allows you to be everything even as you remain nothing. “Fled is that music—Do I wake or sleep?”

Swan vs. Torso

You see an analogous ambivalence in Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo.”

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast's fur:would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.(trans Stephen Mitchell)

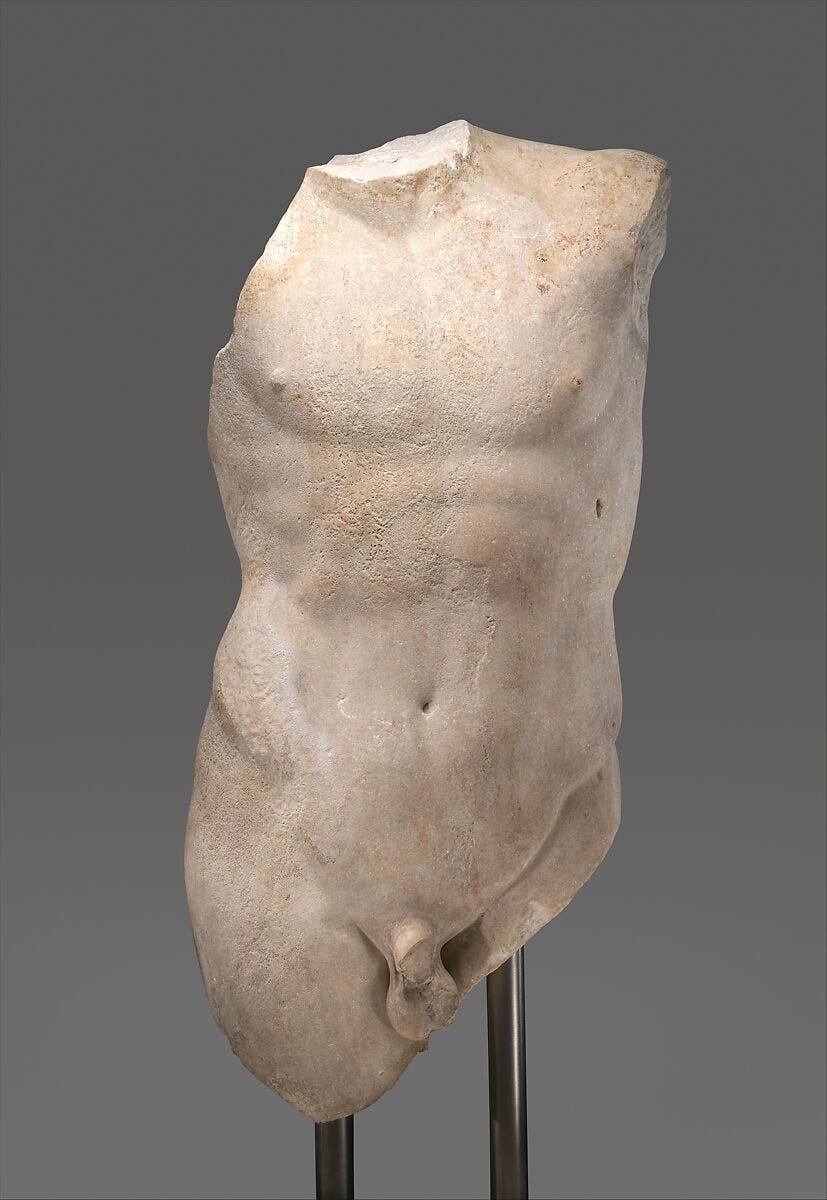

Image: marble torso of the so-called Apollo Lykeios, The Met

Rilke’s poem is obsessed with negation. It starts with the head we can’t see, and then insists that head must be there, spiritually, or else the statue would be underwhelming. Add in the weird reference to the smiling phallus and the poem takes on inescapable Freudian overtones. The God/father “sees you,” and finds your life (your art? your phallus?) wanting. Flawed art makes you aware of your flaws; and an experience of transcendence (in your head) lands you finally back in an inadequate self.

Oliver lifted the last line of the swan from Rilke, but she dispenses with the vacillating castration anxiety for a more straightforward rhetoric of empowerment.

And have you too finally figured out what beauty is for?

And have you changed your life?

Keats is uncertain about transcendence, or even about the role of beauty. Oliver is not. Nature in her telling offers a clear blueprint for individual action; you are the bird, and its ascent is supposed to show you how to soar from your life into a less restrained, more fulfilled selfness.

“The Swan” presents nature as instructive. But, as in Keats, “bird” here is a not-very-buried metaphor for “poesy.” Oliver’s poem is about the swan; at the same time, the swan is a metaphor for the poem. Viewing the swan is a spiritual experience—but you’re not actually viewing the swan. You’re reading a poem. And that poem mimics the swan’s sweep and ascent. The last lines are maybe telling you to go out and watch some swans. But they’re definitely telling you to read this poem as a spiritual practice. It is the poem you see drifting on the black river; it is the poem that you hear with its shrill, dark music. It is the poem that gives you wings. That’s why Oliver ends with a Rilke reference; she’s writing a poem about a poem, literally and figuratively.

That’s also why I find “The Swan” so off-putting. The poem, to me, feels like it’s an incessant hectoring demand that you acknowledge the awesomeness of Mary Oliver’s poetry. “I have found the path to transcendence! Do you get it? Do you get it? Honk!”

Oliver insists that as a poet, and a spiritual leader, she’s found what beauty is for, and can transmit it to you, the listener, via a life-changing infusion. Obviously, a lot of people find that powerful. For me, though, the art of Keats and Rilke—or for that matter of Bonnie Raitt and Gloria Gaynor—is moving because it has space for human weakness and human uncertainty.

Verse and song are meant to take you out of yourself. But since we’re not swans, or nightingales, or gods, we’re always dragging that torso around with us, even if we manage, occasionally and briefly, to get off the ground.

Thank you for this! My oh-so-spiritually-enlightened friends love to post Mary Oliver poems on Facebook - “What will you do with your one wild and beautiful life?” is now indelibly etched into my brain - and I’ve always felt vaguely inadequate because I just don’t find them all that inspirational. Your piece makes me realize why. And my gut-reaction answer to Mary’s poetic question is something like, “I dunno, maybe read a good book?”

Now I am reading up on her, and it is interesting. She is from Ohio...in the tradition of Whitman and Dickinson (though unlike them in some ways) and she gets a lot of flack. But if a poet’s job is to let you into their mentality, then she succeeds. Maybe it’s a midwestern mentality! I couldn’t handle the midwest. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/11/27/what-mary-olivers-critics-dont-understand