Why I’m Okay With Being Called a ‘Content Creator’

Widgets unite!

“To hear people talk about ‘content’ makes me feel like the stuffing inside a sofa cushion,” Emma Thompson told an audience of drama students last week. “You don’t want to hear your stories described as ‘content’ or your acting or your producing described as ‘content.’ That’s just like coffee grounds in the sink or something.”

I get where Thompson is coming from. When you’re an actor or a writer (like me!) you want to see yourself as a valuable artist, unique and irreplaceable. “No one but me,” you want to think, “could craft this insightful op-ed, no one but me could limn this lovely poem.” You want to feel like people are there to listen to you in particular and to be enlightened by what you have to say and how you say it.

“Content creator,” in contrast, makes you sound like you don’t matter at all. You’re just a bland, interchangeable gear grinding out bland interchangeable gunk for not very discriminating gunk consumers. Someone else could replace you easily on the assembly line of content; someone else could dump their words into the SEO algorithm. You’re just stuffing or coffee grounds. You’re a widget. Who wants to be a widget?

Obviously, Emma Thompson doesn’t want to be a widget. And there’s a strong case that she is not a widget. She’s Emma Thompson! When she’s in a movie, they put her name on the poster, because people come to see Emma Thompson, in particular; she’s not easily replaced. No wonder she thinks “content” is a “misleading” term for her work. She’s not content; she’s Emma Thompson!

If you’re not as successful as Emma Thompson, though, things look a little different. There are a handful of people who maybe want to read words by Noah Berlatsky in particular. But for the most part…well. My words aren’t really about my special suchness. People read me because I’m filling some niche they happen to want filled. I’m a content creator.

And while I could struggle and try to fool myself about that, I’d rather embrace it. Being an anonymous widget isn’t necessarily especially inspiring, and it’s obviously not a path to stardom or success. It is, though, potentially a basis for solidarity with other anonymous widgets.

Art vs. Starbucks

Thompson, speaking to the drama students, argues that art should be “completely authentic.” When art is authentic, she says, it touches something inside viewers. Authentic art is real, and it will find its own audience.

That’s a common view of art and of what art should do. It’s also a view of art that’s at odds with the general experience of labor. Most jobs aren’t really “authentic,” or meant to be authentic. A Starbucks barista isn’t supposed to make an “authentic” cup of coffee that expresses who they are. They’re supposed to just make the coffee to standard, so you get what you paid for.

This is one way of saying that most people are, and are even supposed to be, alienated from the product of their labor. You aren’t working to make something you, personally, approve of; you’re working for a boss, to make something the way they want it made. You don’t have control of what you do in conception, in process, in final form. You’re a thing, directed by someone else.

And since you aren’t important in the experience of the product, it’s easy to alienate you from the labor in another sense—by siphoning the value you create away for the bosses/capitalist pigs. Anyone can make a coffee the Starbucks way, which means you don’t have to be the one to make it. The bosses can underpay you, secure in the knowledge that if you object, they can just fire you and hire another widget.

So, how can artists protect themselves from being Starbucksed into irrelevance?

Well, one way is to insist that art isn’t like making coffee. When you turn to Netflix or HBO for your evening’s entertainment, you’re not looking for just anyone to make you a cup of coffee. You’re looking for an authentic experience of pathos, laughter, meaningfulness. And to get that authentic experience, you need someone in particular, like Emma Thompson, to share her true self with you.

Again, this is in fact a model that describes, to some degree, the career of Emma Thompson. You can’t replace her with just another barista. She’s a name actor, a celebrity, a beloved icon. Or, to put it another way, she is a success.

Success Isn’t a Model for Everyone

Most artists (not excluding me) dream of success and of being appreciated for their authentic individuality in a way that allows them to control their own work and collect the fruits of their own labor. On Substack Notes, much of the inter-writer discussion is precisely about this; how do you cultivate an audience that wants to read your work in particular? How do you create a brand that is uniquely yours, and which you alone, and no one else, can leverage? How do you become Emma Thompson—but, you know, in your own unique way, that even Emma Thompson can’t reproduce?

I’m not immune to this dream. I would like people to follow me because they want what I, in particular can offer (poems! Cat pics! Weird essays about how no one owes you hope!) I want people to buy my books and think that I have something special to offer. I want to be an authentic artist, not a content creator.

But the thing about success is it is, by definition, something available only to the few. “Success” means you have distinguished yourself; it means people want you and no one else.

I suppose in theory everyone could shine with special suchness, but in practice, being distinguished from your peers ultimately means that your peers aren’t distinguished. Everyone’s name can’t be on the marquee. Someone has to play the barista with no lines who hands Emma Thompson her coffee. A movie generally only has room for a couple of big stars; if everybody had purple badges on substack, they’d be a lot less impressive—and the site probably wouldn’t even bother with them.

I’m not going to ever get a purple badge on substack, I’m not going to be Emma Thompson. Like most writers, and most artists, I’m not really valued for my special suchness as much as for my ability to crank out content on deadline to spec. Yes, I write.a substack, where people will pay me for a broader range of things, which is great! But I also write op-eds on breaking news because there’s a market for it. And I do a fair bit of anonymous work-for-hire things too—ghost writing, educational writing, copy, whatever. It’s not authentic, really. It’s not special. It’s content.

Content Creators Are Workers

Like the Starbucks barista, or an assembly line worker, or a convenience store clerk, my labor isn’t valuable because it’s mine; it’s valuable (to the extent it is) because I’m feeding the market something it (momentarily, at least) wants. The term “content creator” accurately captures my anonymity and irrelevance. I’m no one special. I’m just a worker.

And again, most people who aspire to artdom want to be more than just workers. And sure, I’ll call myself a poet sometimes in my dreams or where no one can see me. But there are advantages to being just a worker too—because, and this is the cool part, there are a lot of workers. Being special is great, but there’s also something to be said for common experiences and common interests. There’s something to be said for solidarity.

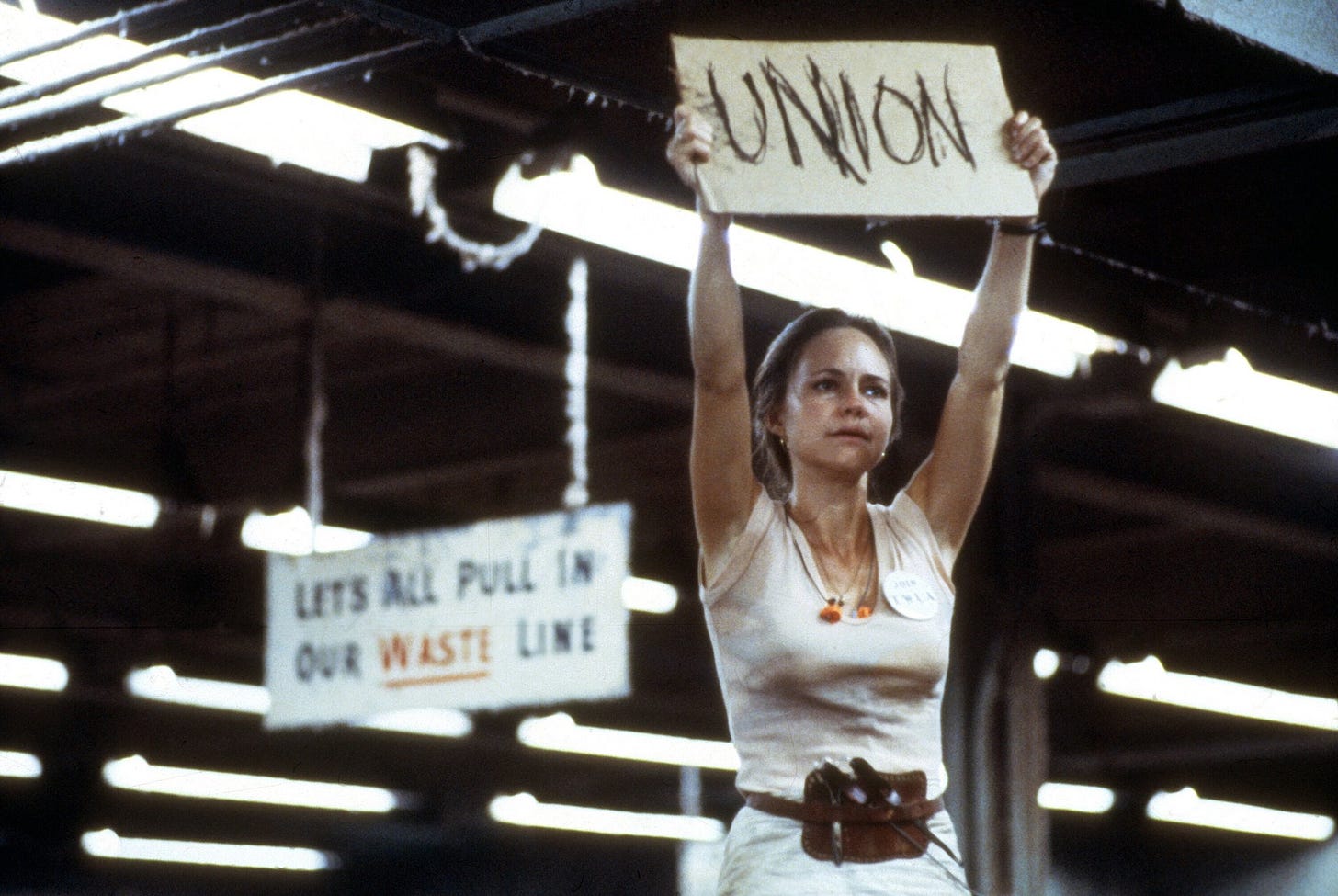

The virtues of solidarity are especially clear right now; after a five month strike, the Hollywood writer’s union (WGA) appears to have won a historic victory. Some of those Hollywood writers are high profile successes who are going to work on celebrated films or television shows. Some are semi-anonymous nobodies, who write opening monologues for talk shows or script despised reality television shows. But it doesn’t matter if they’re doing work that is authentic to them, or if they’re just hitting a deadline for a paycheck. They marched on the picket lines together, and they won a contract together, stars and content creators alike.

It's true that “content creator” is kind of an ugly term. But work is a kind of ugly thing under capitalism. It’s exploitive; it’s tedious; it’s often soul-killing. Sometimes it’s worse than soul-killing.

Work can also be the basis for resistance, though. When you’re special, you’re special alone up on that marquee. But if you’re a widget grinding, you can choose to grind stronger together.

You make the point well, and that’s why I subscribe to your writing. Your specific voice and critical perspectives are apparent in all of the writing you do, even the articles you deem ‘content.’ It’s true that only some talented people will aggregate sufficient crowds to be considered successful, but that doesn’t change the actual work that’s being done by artists with smaller groups of followers. If the same body of work makes you a marquee name in one universe and a starving artist in another, the only difference is the response to the work. It all depends on how you define success for yourself.

I think the word ‘content’ devalues a person’s work. It spotlights that the work produced on Substack most benefits the owners of Substack. That can be true and also something writers can resist, in solidarity as you say.

It sounds to me like you're saying that there is art and there is content and sometimes they're the same thing but sometimes they're two entirely separate things, and that one person can do both of them? But just as that might mean you can create "content" with no pretensions towards "art," you can create "art" that does not want to be "content." I mean, sometimes the medium IS the point, and the things "contained" are grist / fodder / etc., but sometimes the medium is just the platform the art is placed on.