Yeats’ "The Second Coming" Isn’t Antifascist

Apocalyptic imaginings generally aren’t

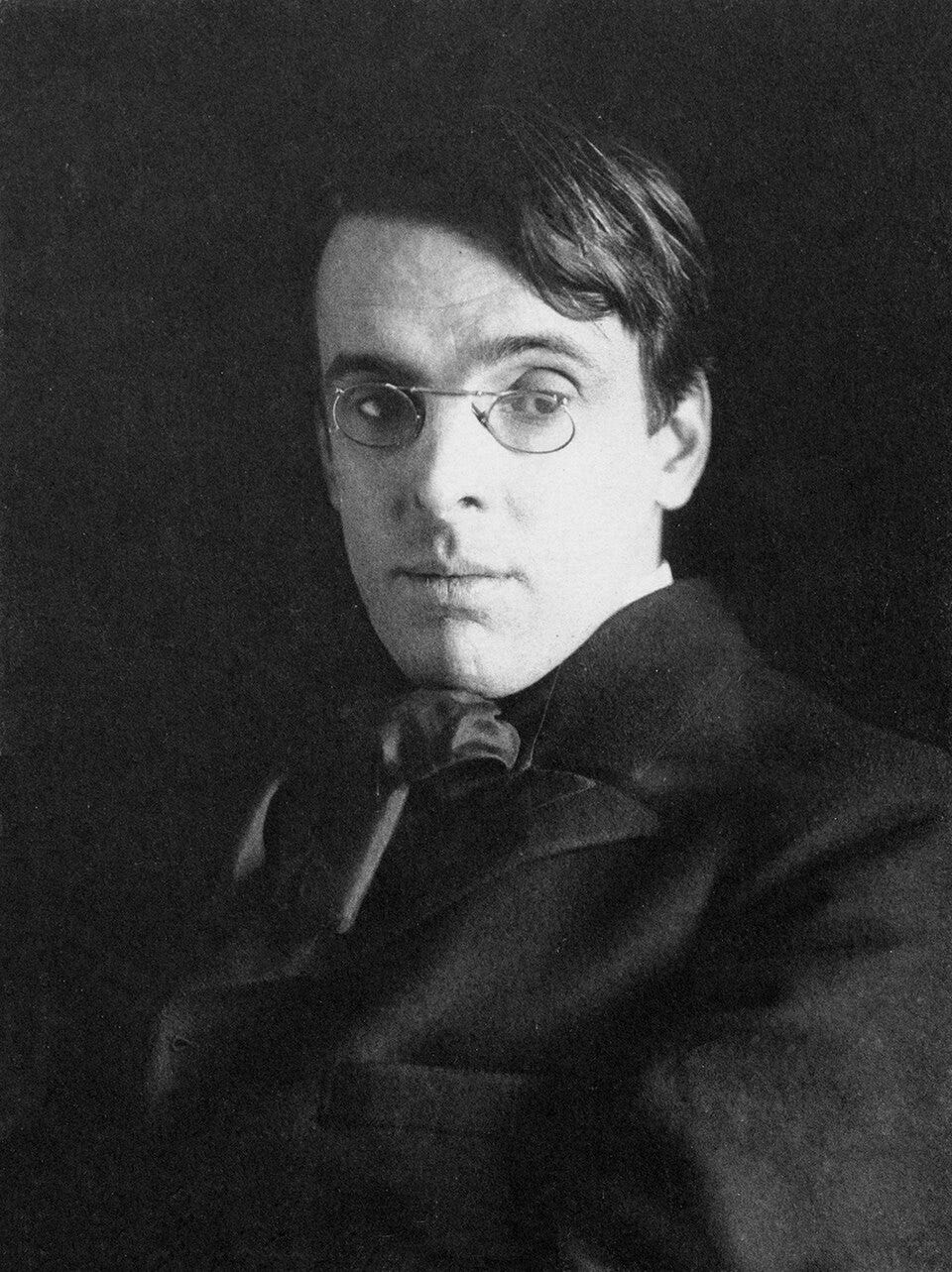

Yeats wrote his poem “The Second Coming” in 1919 and it was published in 1920. No one thinks he was consciously predicting Trump or a descent into fascism. But a lot of people do think that Yeats was warning against some vague authoritarianism-related disaster.

“Was Yeats’ ‘The Second Coming’ Really About Donald Trump?” asked a headline at LitHub in 2016. “So much of [what Yeats writes] applies so directly to what we are facing that it makes me shudder at the prescience of the poet,” a writer mused in the LA Progressive in 2025. Nor are they alone; social media is turning and turning with people convinced that mere anarchy has been unleashed upon us and that Trump is the rough beast slouching towards Bethlehem to be orangely born.

The problem with this interpretation of the poem is that Yeats liked authoritarianism. He disliked liberal democracy, and in the interwar period came to support fascist movements, materially and ideologically. That means that “The Second Coming” is a lot closer to fascist propaganda than to any sort of antifascist statement. And while Yeats is dead and our approval or disapproval of him is largely irrelevant, it does seem important right now to distinguish the kind of rhetoric that opposes fascism and the kind of rhetoric that very much does not.

—

Everything Is Horrible is entirely funded by readers. If you value my writing, please consider becoming a paid subscriber; it’s $50/yr, $5/month.

The New Birth

Everyone knows the last couple lines of Yeats’ famous poem, but it’s worth revisiting the whole thing:

The Second Coming

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Yeats is channeling Christian apocalyptic thinking here in part. He’s also influenced (as Wikipedia explains) by his own quasi-mystical notions about historical epochs or “gyres”—notions which he interpolated and bastardized from Nietzsche.

For Yeats, the gyres—spinning and succeeding each other in an inevitable progression which (like a falcon loosed) cannot be called back—are Christian morality and pagan morality. Yeats was writing after the first world war and in the middle of influenza pandemic and civil upheaval in Ireland. In the midst of chaos and despair, he anticipates a reversal of the moral order—a shuffling off of the Christian status quo of mercy and love, and a birth of a harsher, more brutal status quo, “blank and pitiless as the sun.”

Decadence and Retribution

Obviously, when we today hear someone say that Christianity is going to be replaced by a brutal Nietzschean order of pitilessness, we say, “holy shit, that sounds like fascism. That seems bad!”

Yeats’ imagery is frightening and ominous too. But that doesn’t exactly mean that he’s opposed to that rough beast being born. On the contrary, Yeats was not only a fan of Nietzsche; he was a supporter of fascist movements in Ireland.

Yeats supported Irish nationalism. But, as an Anglo-Irish intellectual, he feared the rise of a Catholic state, which he associated with what he saw as a debased and ignorant public linked to the “filthy modern tide” of capitalism and mass culture. In order to stem this danger, he embraced the fascist Irish Blueshirt movement, explaining that “I find myself constantly urging the despotic rule of the educated classes as the only end to our troubles.” He composed a marching song for the Blueshirts that included the line, “What’s equality? Muck in the yard!”

Yeats eventually distanced himself from the Blueshirts, but not because they were opponents of democracy. Rather, he thought they weren’t sufficiently aristocratic and elitist. He wanted a more hierarchical, less mass fascism—one that more viciously rejected “base born products of base beds”, to use the eugenics-tinged phrase Yeats included in his famous poem “Under Ben Bulben.”

In this context, it’s clear that the first stanza of “The Second Coming” is not a warning about fascism. It’s a warning about socialism and/or democracy. “The falcon cannot hear the falconer” is a lament at the failure of righteous authority and hierarchy; “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;/Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,” is a warning against anarchists and communists and rabble. When Yeats says “the best lack all intensity” he’s talking about people like himself—intellectuals, but also white men of elevated social standing, including the aristocracy and the wealthy. And “the worst” who are “full of passionate intensity” are the lower classes—those who should know their place, but have now slipped their hood and gone flying every which way.

The second stanza can be read as a continuation of the first; Yeats is imagining the dark, terrifying world in which the masses get to do things like vote and have a say in their own government. The imagery, though, isn’t quite right; the terrible sphinx “moving its slow thighs” seems like a symbol of empire and nobility, not of dissolution, and the rough beast at Bethlehem sure sounds like a mirror image of Christ the King.

The end of the poem, in this reading, would be a reaction to, rather than an extension of, the first. Yeats is imagining the (fascist) backlash to left uprising—a fascist backlash which is frightening and bleak, but which is also in its way exhilarating. The reason that the final lines of the poem are so indelible and so often quoted is because they encourage you to (at least ambivalently) identify with the force of apocalypse—to embrace the coming reversal of morals as a perhaps regrettable, but nonetheless necessary rebuke to the rabble, the communists, the anarchists, the Catholics. Fascism will restore order and grandeur. The price might be high, but Yeats made it clear in his writings that he was willing to see it paid. (He died in 1939; there’s no way to know whether Hitler would have changed his mind or led him, like his friend Ezra Pound, to double down.)

Apocalypse isn’t generally an antifascist mode

Yeats’ poem parallels Chris Hedges’ Instagram sermon about how the US deserves Trump for our sins, or Bill Paxton’s falsetto, “Game over!” as he prays for the xenomorphs to take him. Apocalypse generally involves predictions of inevitable doom, and that assertion of inevitability—the claim to be the one who knows, the implicit (or explicit) denigration of those who don’t—functions as an empowerment fantasy. Empowering yourself by imagining the sweeping destruction of your inferiors doesn’t always, always have to be fascist, I guess. But it certainly leans in that direction.

Antifascism requires solidarity, which means you can’t pump yourself up by preening as you contemplate everyone else’s death. And, relatedly, it requires a commitment to, and an assertion of, agency—not for one poet or one king or one prophet, but for everyone.

Thus, antifascist apocalypse stories—like N.K. Jemisin’s The Broken Earth trilogy, or the film The Cabin in The Woods—insist on portraying the choices not of rulers, but of those targeted for violence, discrimination, and death. There’s a big difference between, “the world is going to hell and it’s inevitably going to burn down, ha ha” and “the current system is unbearably oppressive, and those who are oppressed have the right and the responsibility to overthrow it.” The first is a genocidal fantasy; the second is a call for a slave revolt.

And yet, even though the contrast there is stark, we seem to have a lot of trouble distinguishing the one from the other. Babbling about rough beasts or games that are over feels powerful, and so it seems like a rebuke to power. Hand-waving the possibility of agency and change feels like you’re seizing an even more powerful agency. The step-by-step drudgery of solidarity and resistance lacks the mighty ring of inevitability. It doesn’t have the grandeur of “twenty centuries of stony sleep.”

Yeats makes us identify with the slow grandeur of epochs; he makes our encounter with Trump feel mythic. But Trump isn’t a myth. He’s a boring, grimy truth, and granting him world-historical inevitability is just another fascist lie. “The Second Coming” is impressive, but so is “Triumph of the Will”. Neither of them is the best place to look for antifascist insight or inspiration.

---

Note to All Nazis, Fascists and Klansmen

Langston HughesYou delight,

So it would seem,

At making mince-meat of my dream.If you keep on,

Before you’re through,

I’ll make mince-meat

Out of you.

Great essay. Comparing it to Leni Riefenstahl’s film was spot on.

By contrast, Trump’s coterie see themselves as elite in the power and $$ spheres, but they lack any interest in artistic mastery. It’s all, as you say, gaudy and commonplace, which suits Trump fine.

Powerful argument and an impressive interpretation pushing against so manny assumptions. I particularly appreciate your take on apocalyptic visions. Considering that empowerment and agency are necessary to fight fascism, not the embrace of apocalypse—wouldn’t this call into question the seeming hopelessness of the name of this Substack: “Everything is Horrible”? Surely there is something less horrible—and we ought to be grasping for it—all of us—if we are to build in the place of fascism a new world.