AI Art Shows the Value of Disability Aesthetics

The virtues of women laughing with salad and too many fingers.

Image: from the AI women laughing along with salad series.

When people say that all AI art is bad and that AI art can have no worth, I point them to the unsettling brilliance of “Women laughing alone with salad,” by Matthew Nepsa (@blakkfriday.)

The series of images, generated on Midjourney, is basically what it says in the prompt; women laughing uproariously while holding salad bowls.

Image: from the AI women laughing alone with salad series.

However, the women have…too many teeth. Too many fingers. Their faces are too emphatically stretched across their skulls. The salad is too red; too green, too likely to explode. Arms aren’t attached right; eyes are twisted up and seem to be trying to crawl from their sockets. The images provide a terrifying glimpse into the lonely, laughing kitchen of the damned. It’s disturbing, weird, and funny; it’s great art.

Image: from the AI women laughing alone with salad series.

Or is it? Responses to the series have generally been positive, but they’ve also expressed some ambivalence. Are we salad-laughing with the AI, or are we salad-laughing at it? Mary Flannery’s write up in McSweeney’s, for example, focuses on the out of sync details in the images, mocking the AI for its lapses of verisimilitude.

I am an AI-generated human female laughing alone with salad. Hahahaha. What could be better? Why are you looking at me like that?

Is it because I have eight fingers on my left hand? Who doesn’t? After all, this is AI. And thanks to AI, we can have all the fingers and salad and finger salad that we want. Anything is possible.

For Flannery, the images illustrate the failure of AI; the women have too many fingers, they have too many teeth. “This lettuce leaf-prompted laughter is the most natural thing in the world,” Flannery quips—the point being, of course, that the images don’t look natural. Everything is wrong.

Wrong Is Right

The thing is, though, that in modern art of the last 75 years at least, wrongness is…well, right. As scholar Tobin Siebers notes in his classic 2010 work Disability Aesthetics, wrongness—or as he says, “disability”, is “the very factor that establishes works as superior examples of aesthetic beauty.” He goes on

To what concept, other than the idea of disability, might be referred modern art’s love affair with misshapen and twisted bodies, stunning variety of human forms, intense representation of traumatic injury and psychological alienation, and unyielding preoccupation with wounds and tormented flesh?

To illustrate his point, Siebers contrasts works shown at the Nazi Great German Art Exhibit of 1937 with the work of the Degenerate Art exhibit of the same year. Hitler’s favored artists, like sculptor Arno Brecker, showed hyper-perfect human forms—massively muscled men reminiscent of sculpted superheroes. As Siebers says, these statues today don’t look like great art. Precisely because they are so humorlessly healthy, they are kitsch.

Image: Arno Brecker, Readiness. (A nude, muscled man prepares to pull a sword from a scabbard.)

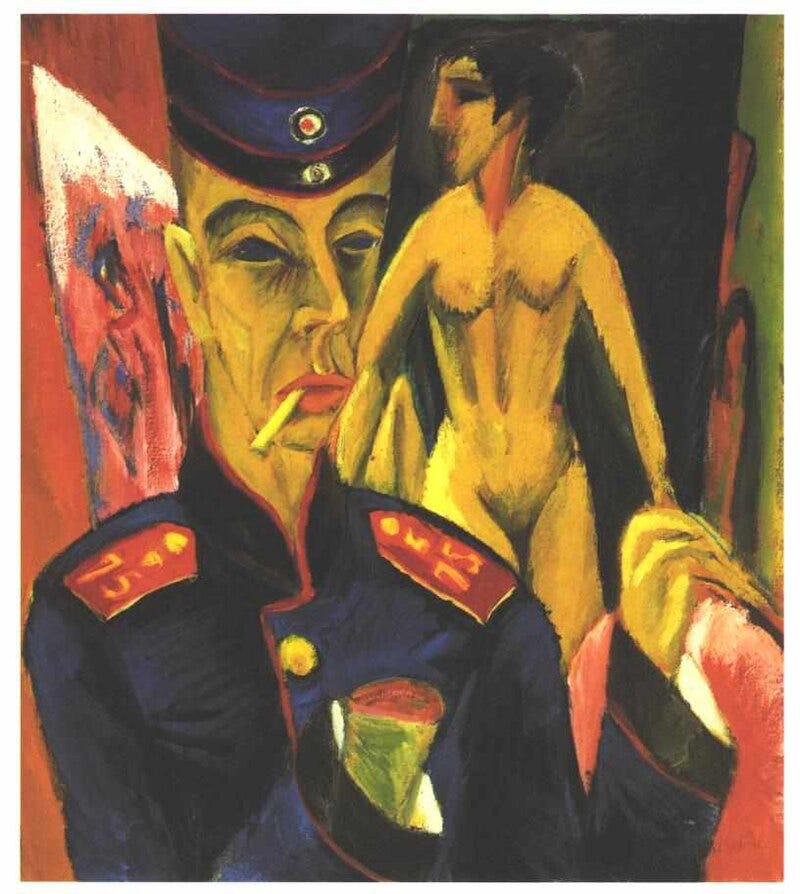

In contrast, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s 1915 Self-Portrait as a Soldier, which juxtaposes the stump of Kirchner’s amputated hand in the foreground with a nude woman in the background, emphasizes not perfection of form, but disability, castration, angst, and anguish.

Image: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s, Self-Portrait as a Soldier

The Nazis exhibited Kirchner’s picture to illustrate society’s sickness and the morbid weakness of Weimar. Today, though, Kirchner’s image is viewed as profound, courageous, and still relevant. It is aesthetically celebrated because it embraces and represents wounded bodies. Or, as Siebers puts it, “good art incorporates disability.”

The Salad Women images clearly, in this sense, incorporate disability. The excessive digits and molars which Flannery points out as signs of robot, non-human confusion are the very aspects of the images which make them interesting, riveting—and continuous with modern signifiers of “good art”.

Disability and Diet Culture

The Salad Women incorporate disability through representation of deformed or misshapen bodies. They also incorporate disability through theme. They are about what it means to have a “healthy” body.

The prompt “Women laughing alone with salad” references, or is inspired by, stock art and advertising images that show women eating salad while emoting over-enthusiastically. As Dr. Wrenn discusses in this 2015 article :

The consumption of vegetables (with salad being the ubiquitous cliché) is a highly feminized behavior. Gender codes also manifest in the regular hyper-emotionality of women in advertising. That is, women are often portrayed as having inappropriately extreme emotional responses. Representation of this kind adds to the cultural understanding of womanhood as infantile, irrational, and immature. In this case, even a little bit insane. These images reinforce women’s subordinate status. Pairing hyper-emotive women with hyper-feminized food items makes for a perfect storm in sexist imagery.

Image: Stock art image of thin white woman eating salad and laughing. She has the right number of teeth.

The laughing salad images may, as Wrenn says, enforce a hierarchy of men over women. I think they also insist on a hierarchy among women, though.

The happy salad women are thin, they are eating right, and they are filled with aggressive joy. The message to women is that by dieting, they too should become thin and filled with laughter. The images frame certain body types as healthy and happy, and imply, through exclusion, that other bodies are ugly, sad, unhealthy—and by analogy, disabled.

The stock images of women laughing with salad are kitsch for the same reason Brecker’s sculptures are kitsch. They represent perfect bodies fulfilling their perfect gendered destinies—whether that destiny involves muscles, solemnity and virility or thinness, healthy diet choices, and smiles.

Image: from the AI women laughing alone with salad series.

Kirchner’s soldier can be seen as a parody and rejection of myths of soldierly masculinity and power. In the same way, the AI generated women laughing with salad images are a parody of female beauty standards and diet culture. They draw out the monstrous disability at the core of diet culture’s cult of health by underlining the manic obsessiveness and self-distortion implicit in fetishizing salad and diet as an eroticized mechanism of self-regulation.

Or, as Flannery puts it:

even if I were miserable, nobody could tell. That’s the real magic of AI. Would a miserable person be laughing it up like this? Would a depressed person laugh with a salad? I don’t think so. Nobody would look at this face and this exploding salad and think, That woman is crushing what remains of her sanity into a tiny wad she plans to hurl out of the nearest window. Nobody could possibly think that. That’s the best part. Don’t you want to try it?

AI And the Mentally Disabled

As that last passage demonstrates, Flannery doesn’t just point out the physical errors and disabilities perpetrated by AI. She also suggests that the the woman in the picture—and I think by extension the AI itself—is mentally disabled or insane.

Flannery isn’t alone; AI art is often denigrated on the grounds that its cognition is flawed or inferior, and that the images it produces are therefore also somehow broken or empty. Thus, a games writer named Matt S. titled one of his articles “AI is already ruining games and making the industry dumb”—explicitly suggesting that AI is bad because it is connected to disability (“dumb”). He then went on to argue

AI art is shallow, lacks meaning and thought and, no matter how pretty you might find the results of its algorithms, those algorithms are fundamentally inferior. No thought went into them. They are, quite literally, nothing more than a best guess at a pretty picture.

For Matt S., art must be created by “thought,” and specifically by superior, not “inferior”, thought. As Siebers says, this validation of thinkful art is quite common.

Traditionally, we understand that art originates in genius, but genius is really at a minimum only the name for an intelligence large enough to plan and execute works of art—an intelligence that usually goes by the name of ‘intention.”

Siebers then points out that this vision of art as intentional excludes the mentally disabled as art makers. “Defective or impaired intelligence cannot make art according to this rule,” he says. “Mental disability represents an absolute rupture with the work of art.”

And yet, Siebers argues, there are numerous examples of art created by mentally disabled people. He focuses especially on Judith Scott, a deaf woman with Downs syndrome who was largely nonverbal, and had never visited an art museum. Scott almost certainly did not intend to make art in the way we usually speak about “intention” and “art.” Nonetheless, her fiber sculptures—in which she wraps common objects in layers and layers of thread—are widely, and justly, admired as an important contribution to contemporary art.

Image: Judith Scott, untitled, no date. An image of red, yellow, blue fiber wrapped around what looks like vacuum cleaner tubes, creating a ovalish shaped sculpture.

Siebers notes that Scott, “had no view to exhibit her work, no audience in mind” and that; her sculptures “do not distinguish between front and back.” This means, for Siebers, that Scott’s “work projects a sense of independence and autonomy almost unparalleled in the sculptural medium.”

In other words, Scott’s lack of intention contributes to the beauty and uniqueness of the art. Just as Kirchner’s refusal to represent perfect bodies made his painting modern, so Scott’s challenge to models of genius is part of why her sculptures are valuable.

Imperfect AI

As Siebers says, our sense of aesthetics incorporates disability, even when (especially when?) we disavow that disability. Flannery’s ode to those salad women laughing takes the rhetorical position that the images are ridiculous, ugly, and wrong because they present imperfect bodies, and because they seem to be generated by a process that is divorced from intent and understanding.

Yet, the images have power precisely because they present images of distorted bodies apparently created without intent, or created by a mind that does not understand bodies or the physical rules of salad. AI is criticized for its imperfections of representation and cognition, but it is precisely those imperfections that link AI to ideas of disability which Siebers identifies as core to contemporary aesthetics.

The point here isn’t that you have to love AI. On the contrary, there are lots of reasons to be wary of AI’s use in art. Many AI art generators are trained on, and scoop up, copyrighted images in ways that arguably violate intellectual property rights. Many corporations see AI as a way to replace human artists on the cheap. AI art requires an enormous energy use, and is damaging to the environment.

These pragmatic concerns about AI, though, are often accompanied by moral, aesthetic attacks that dwell on AI’s tendency to create imperfect bodies or images and on its lack of intention or intelligence. AI is targeted, in other words, in ways that echo reactionary denunciations of much modern art as “sick” or unhealthy. AI art, and AI itself, are delegitimized by linking them to discourses of disability—discourses which, paradoxically, underpin and validate much of the art we consider most important today.

Image: from the AI women laughing alone with salad series.

The limitations of AI are in themselves a kind of disability aesthetic, linked to representations of imperfect bodies and to creation without geniues. Those weird too-healthy AI salad eaters remind us of the dangers of worshipping perfect forms and perfect aesthetics. They tell us, with all those teeth, that we should be careful not to use disability stigma to posit a pure or healthy art as an alternative to AI. As Siebers reminds us:

The aesthetic desire to transform the human revolutionizes beauty by claiming disability as the form of physical and mental diversity with the greatest potential for aesthetic representation. The figure of disability checks out of the asylum, the sick house, and the hospital to take up residence in the art gallery, the museum, and the public square. Disability is now and will be in the future an aesthetic value in itself.

Wow. What a great fucking article.

I really like this perspective. One thing I am a little stuck on is the concept of “intent” - it feels a little too neat to compare the lack of intent in AI to the form of intent in the work of an artist like Judith Scott, who surely HAD an intent of some sort in her creative process. Disabled artists challenge the concept of artistic “genius,” but to me because there is a *different* form of thinking going on, not a lack of thinking, or a total absence of thinking like in AI. Not sure if I am being clear, or maybe this is an oversimplification of what you are saying. Also, in AI art there is the added layer of the input of the human who interacted with the AI, who I had assumed intended/expected the images to be off kilter.