Anne Tyler Doesn't Need to Worry

White writers aren't oppressed.

This ran last year, but isn’t online any more. These issues still seem relevant, so thought I’d reshare.

_______

Who is allowed to write what? What novelists have the opportunity, the means, and the capacity to write which stories? How has history affected who gets to represent whom?

In an interview with the Sunday Times, novelist Anne Tyler weighed in to address these questions without much insight or context. “I’m astonished by the appropriation issue,” she said. “It would be very foolish for me to write, let’s say, a novel from the viewpoint of a black man, but I think I should be allowed to do it.”

Tyler is channeling one common, but confused perspective. She worries that because of concerns about cultural appropriation, white writers will not be able to include Black characters in their work—or that straight writers will not be able to include queer characters, or men will not be able to write about women. In this imagined progressive dystopia, writers are only allowed to pen stories about people like themselves.

As many people pointed out, this dystopia does not exist, and there are no rules which prevent white writers from including Black characters or people of color in their books or movies or television shows. As just a couple of examples, Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt, written by a white author about Mexican immigrant experiences, was published in 2020 to widely positive reviews, and was an Oprah Book Club Pick. The same year, the television show Lovecraft Country, about Black characters dealing with eldritch horrors, premiered on HBO. It was based on the successful 2016 novel by Matt Ruff, who is white.

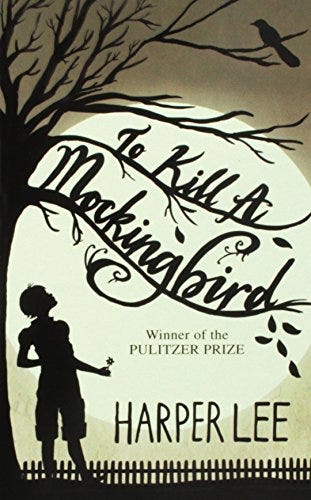

This shouldn’t be surprising, since historically, the most successful and iconic books about Black experience, and about all experience, have been by white people, and especially by white men. Probably the best know Black character in literature is Othello. The most canonical American Black character in literature is probably Jim, from Huckleberry Finn. The novel about Black experience that is most familiar to most high school students is To Kill a Mockingbird. The most successful film ever about Black history is Gone With the Wind. All of these works were created by white people, with a primarily white audience in mind.

Why have white artists created so many of the most culturally validated art about Black people? The answer is straightforward: racism.

Since the establishment of modern literary genres and markets in the last few hundred years, white people have had more money, more education, and more access to literary institutions and distribution networks than Black people, who over that time period have been variously enslaved, impoverished, and discriminated against. In the 1930s, when racism was ascendant and North and South had joined in a vicious backlash against post-Civil War civil rights gains, Margaret Mitchell’s novel of Southern nostalgia could get picked up by Hollywood and made into a huge motion picture. No Black author was in a position to have their work similarly celebrated.

White people continue to dominate literary markets and cultural production in general. A New York Times survey in 2020 found that non-Hispanic white authors made up 89% of books published by the five largest publishers, even though they accounted for only 60% of the US population. Film is even more overwhelmingly white; 90% of directors of films that made over $250,000 were white according to a 2018 study. Film rights are a huge potential source of income for authors. The fact that the film industry is so overwhelmingly homogenous creates obvious barriers for writers who fall outside of that one demographic.

Tyler’s suggestion that white authors are being limited in what they can write is, then, precisely backwards. It is overwhelmingly, historically, and currently Black and POC authors who face barriers to telling their own stories, or anyone’s stories. Black and POC authors are less likely to be able to get book deals; they are less likely to get movie deals. They are less likely to be able to speak.

There has started to be mild pushback in the last few years, as Black creators and POC creators have argued that they should be allowed to tell their own stories. White writers are no longer the default in precisely the same way they once were. They can no longer assume that everyone uniformly will agree that they should be the ones in the position to tell all the stories all the time.

This pushback can lead to some uncomfortable conversations for Tyler or for other white writers. It may encourage publishers to think some uncomfortable thoughts about their catalogs, and about who gets to speak about what. But that’s a pretty mild corrective to a history in which Black stories and Black characters have been so frequently defined by white writers. And even today, the people who have the most trouble accessing the resources and markets they’d need to tell Black stories remain Black.

I could not help but read and think about Critical Race Theory. The kind of CRT that indeed requires some intellectual heft, not the misnamed CRT which equates to banning the accurate portrayal of the Black experience in schools. Now, I'm at the starting line with my understanding of it but I am expanding my mind more by learning more about it.

Awesome take on the power of white art highlighting racism. I've never watched Gone With the Wind. My mom loved it, I know that. I probably should watch it for the first time. In retrospect as a straight white male growing up in the 1980s, they did a pretty poor job marketing the movie to me.