Berthe Morisot and Manly Labor, Then and Now

The impressionists dream of empowering work

The impressionists are stereotypically associated with pretty flowers, colorful landscapes, and bourgeois leisure, but much of their work was in fact devoted to portraying…work. The industrial revolution and urbanization in the nineteenth century created new concentrations and a new visibility for urban labor. Painters like Gustave Caillebotte responded with canvases that mixed fascination and identification.

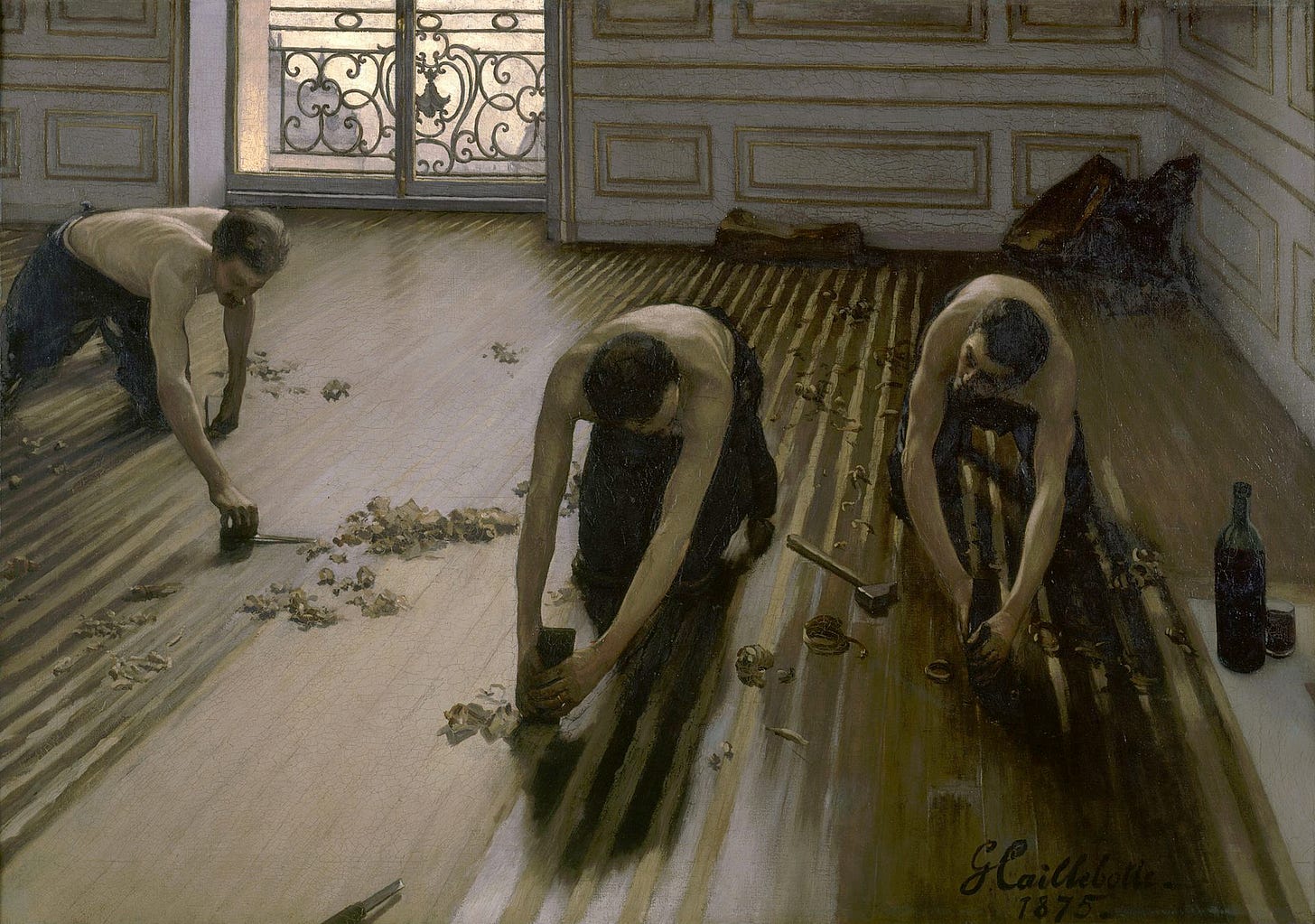

The Floor Planers from 1875 shows workmen stripping an interior floor with light streaming through a balcony window. The image is both a slice of urban life, and a self-referential metaphor; the lines that the men scrape in the floor are literally the lines that Caillebotte paints; the floor shavings scattered around the floor are (again literally) daubs of paint that Caillebotte scatters on the canvas. The men’s labor is also Caillebotte’s labor; his virtuosity limns and ennobles them, just as their virtuosity and shirtless virility illuminates and ennobles the painter.

—

I loved writing this and I really appreciate that readers support me writing about art and labor and a range of things that pop into my head. If you enjoyed this and would like me to continue to be able to write such things, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s $50/yr, $5/month.

Men and women and labor

The masculinity of the labor is inseparable from the message about labor and about painting as an endeavor. The workers, with their tools and their wine bottle, share an easy camaraderie and sexuality—with Caillebotte, too—as they pull the modern world into being with their hands. In contrast to earlier paintings of village labor which emphasized degradation or traditional rhythms, these men are creating themselves through their work just as Caillebotte creates them, and his own status as painter, worker, genius, through his brush. Art here becomes a kind of unalienated labor, flexing its virile bourgeois selfhood on the city’s new industrial canvas.

Male impressionists tended to identify with, and empower, male laborers in their work. Female workers were treated somewhat differently.

This is an 1869 painting by Edgar Degas titled Woman Ironing. It’s one of his many paintings of laundresses in Paris. Laundering was back-breaking work, and was so poorly paid that women often had to supplement their income with sex work.

The erotic possibilities are not front and center here, but, as in Degas’ paintings of ballet dancers, they are close the surface. Degas is laboring with the laundress in part as Caillebotte labored with the floor planers; the fabric she works over with her iron is also fabric that Degas is working over with his brush. But her direct stare, seeming to acknowledge the painter or the viewer, is (at least potentially) to see the fabric of her blouse, and the texture of her skin, as also touchable or possessable. The laundress is not creating herself in parallel with Degas’ self-creation; instead, labor, the work of her hands, makes her exploitable, the work of someone else’s hands. Urban space in Caillebotte becomes a stage for self-fashioning. In Degas’ painting, urban space is still a place for male self-fashioning—in part through the potential’s for men created by women’s need to labor.

I don’t want to rule out other readings of the paintings; The Floor Planers, for example, could be seen as homoerotic, and you could argue that Degas is positing a closer identification with the laundress along the lines of many of Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings of sex workers. Still, I think whatever else is going on in these canvases, one work that they are doing is to hammer down a relationship between masculinity, art, and labor. They depict a world in which the work of male artists is recognized as part of a new, empowering urban milieu, in which men can create themselves through the force of genius and labor.

Women’s work

Given the importance of masculine self-making in these paintings, you’d guess that woman impressionists might approach their work, and their work, a bit differently. And sure enough:

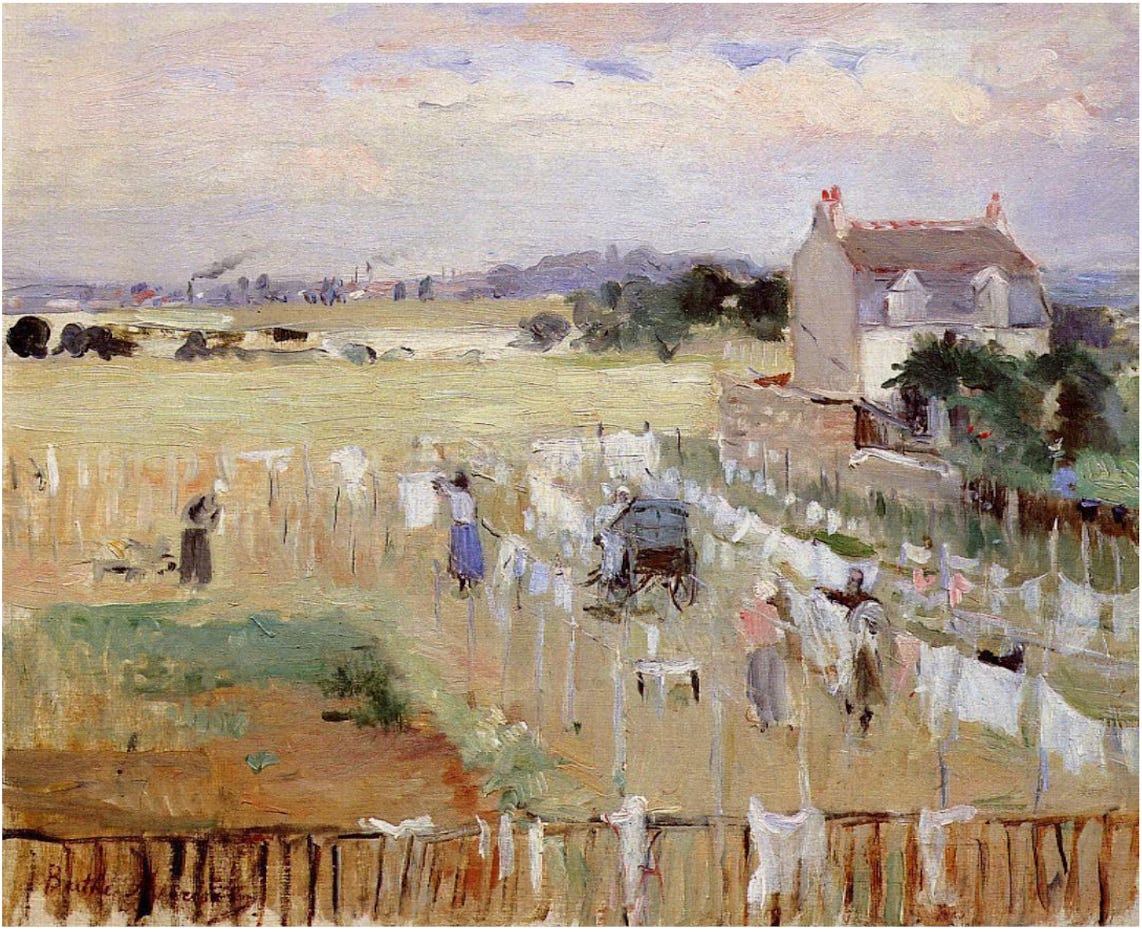

Berthe Morisot’s Hanging The Laundry Out To Dry (1875) has some parallels with The Floor Planers. As in Caillebotte, the labor depicted is self-referential; the women in the painting hang the laundry, those patches of pale color, and Morisot also hangs the laundry by placing it here and there on her canvas. And as in Woman Ironing, the women moving around the laundry merge with their labor as objects of their labor; Morisot creates and touches them as she creates and touches the laundry. As with her male peers, the painting is about Morisot’s virtuosity—the delight of the work is in the way it teeters on the edge of turning into abstract blobs even as it retains its clarity and vividness; you feel like you are watching Morisot conjure people, washing, and labor before your eyes.

Morisot’s canvas, though, is much less eroticized than Caillebotte’s or Degas’—you are, in every sense, more distant from the bodies depicted. In part as a result, there’s less of a sense of (gendered) empowerment. This is not a picture of new urban men creating through their labor a new self. Instead, it’s a scene of domestic labor which is not strikingly distinct from domestic labor of the past; someone (women) still has to do the laundry. The work is neither (newly) empowering nor (newly) degrading, but instead is part of a familiar domestic landscape. If Morisot’s art is like hanging laundry, that may make her a new urban professional, but it also makes her part of the household in which she is embedded—those are her clothes in more than one sense.

Here’s another more famous example.

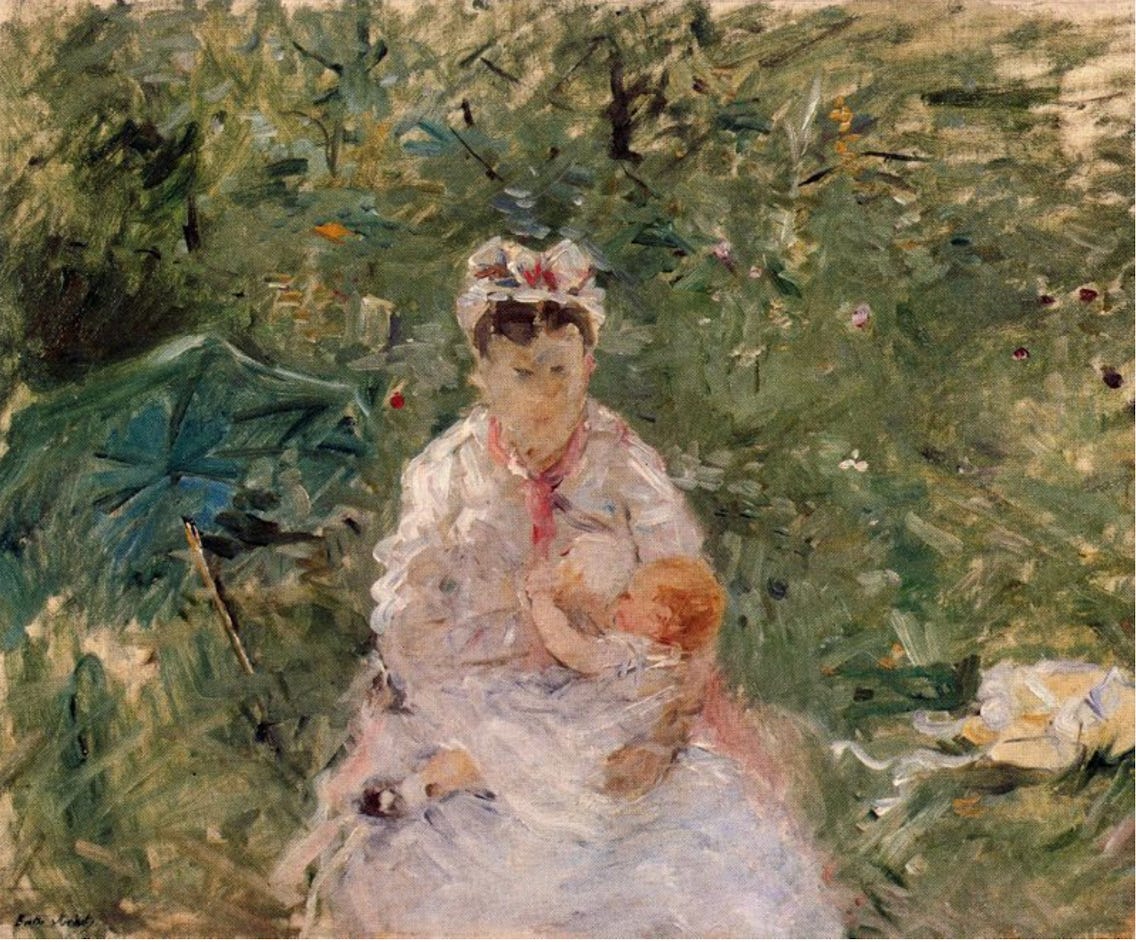

In The Wet Nurse (1881), Morisot paints her newborn daughter Julie nursing. The nurse and child are surrounded by, and blur into, the background greenery—life surging out of the lines between foreground and background, human and garden.

As in The Floor Planners, labor here is treated as joyful and energizing. The parallel between the painter’s labor and the worker’s labor is even more insistent, though; the wet nurse is, after all, literally taking the place of the mother who is painting her. Her labor gives life to Julie, who was created (through labor) by Morisot, and is now created, as paint, through labor, by Morisot.

The painting is certainly a celebration of Morisot as (double) creator. But it also is a painting of the limits of Morisot’s power; she cannot both make the baby (as painter) and make the baby (as nurse); she needs help. That help is the center, and the hinge, of the painting; Morisot is acknowledging, quite directly, that her own labor, however miraculous in at least two sense, is not enough to bring the painting, or the baby, into being. Work is not, in this painting, a springboard to a new urban identity and independence; instead it’s an acknowledgement of the need for others—a need embodied in Julie’s feeding, and in the fact that we can look, with Morisot, at Julie feeding. Morisot can be everywhere in this scene—in every luscious brush stroke and layered daub—because someone else is holding Julie up.

Still working

You could argue that Morisot’s paintings of women’s labor depict the way that the careers of bourgeois women were (and are) dependent on the less well compensated, less prestigious labor of lower-class women. In painting washerwomen and wet nurses, Morisot is painting the labor she must appropriate if her paintings are to exist.

This account of exploitation, appropriation, and class division isn’t wrong. It does tend to dovetail with the vision of labor that Caillebotte and Degas are offering, in which labor is empowering or exploitative, validating or degrading. Morisot—in focusing on domestic work, in acknowledging, and even celebrating, the women who work with her—seems to be trying to find a different way to think about labor and art as complimentary and relational.

Pleas for organic labor relationships are often just a way to tell laborers that they should be happy to be exploited, and Morisot is not painting her way towards a just or egalitarian society. We still do, though, tend to associate labor power and worker empowerment with male manual laborers like the floor planers, while feminized work—especially, but not only, sex work—is still linked to shame, dishonor, and disempowerment. Morisot, in her bourgeois way, tentatively suggests a vision of solidarity built, not on a sense of vaunting masculinity, but on a shared experience of care in labor, and/or of a labor of care. The work in Morisot is not just to create oneself; it’s to create each other.

This is one of my favorite recent posts of yours. I adore Morisot’s work and your piece represents it well. I hadn’t thought of the connection with labor, which was insightful.

How she and male impressionists portrayed women caring for their bodies (bathing, brushing hair…) is also illuminating. As you note, Morisot was a woman of privilege, yet her work creates an intimacy that isn’t acquisitive. Quite unlike her more famous brother in law.

I think you are stretching here. Both painters did few paintings depicting labor. Morisot focused much on the domestic world of women of her class. Caillebotte also did some more or less traditional views of women, i.e., they are basically doing nothing, including nudes, but what is far more interesting about him is that he placed men in roles usually only depicted of women--taking a bath, playing the piano, etc.