Toulouse-Lautrec, Lonely Man in Crisis

Masculinity alone is a problem

As I’ve mentioned a time or two, the crisis of masculinity we hear about from so many furrow-browed pundits is not new. Manly fears about not measuring up to manliness are intrinsic to masculinity; they define what it is to be a man. Men are obsessed with dating and possessing the right woman not because of some sort of biological imperative (which you can satisfy on your own, if you want) but because dating women is how men keep track of their status vis a vis other men—or vis a vis the vision of other men they have in their own heads.

Masculinity is a form of self-policing; an always already impossible attempt to become the ogre father squatting in your own skull. The claim that men today are uniquely lonely is in fact a kind of moral panic about male disempowerment—the fear that without the ability to possess others, men will be unable to take their rightful place in the patriarchy, and will then end up with, and as no one.

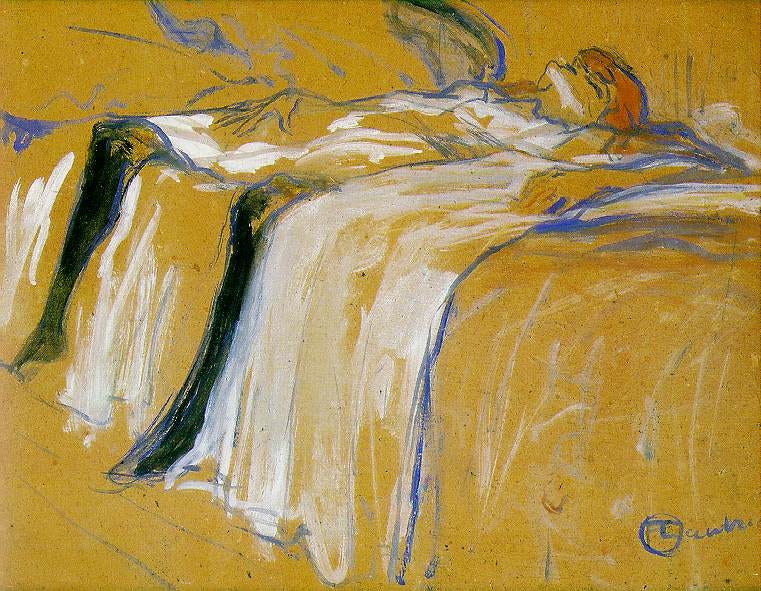

You can find good evidence that the crisis of masculinity has been around for a while in the work of Toulouse-Lautrec. I discussed some of his paintings in a post last month, but I wanted here to focus on his 1896 oil on board painting Alone, which is a simultaneously blunt and layered meditation on manliness, possession, and isolation.

—

This is the sort of article that I can only publish because I publish my own newsletter. But! I can only keep doing that with your support. So if you find this worthwhile/interesting, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s $50/year, $5/month.

—

The man who wasn’t there

Toulouse-Lautrec was the heir of an extremely wealthy noble family; he also had a genetic bone condition which rendered him semi-crippled and very short—he stood only about 4’11. As a result of his condition, he often saw himself, per the biography by Julia Frey, as ugly and undesirable—or as unmanly. He felt he could never court and marry a woman commensurate with his (very high) social class, and he did not believe that any woman would find him attractive in his own right. He did, however, pay for and regularly sleep with sex workers (leading him to contract syphilis at a young age.)

Toulouse-Lautrec’s relationship with the sex workers he hired was ambivalent. He no doubt saw himself to some degree as slumming, the way any noble man might see himself as slumming when he slept with sex workers. Toulouse-Lautrec’s disability, however, made him downwardly mobile and he seems to have strongly identified with other marginalized people—including sex workers and lesbians. His investment was further complicated by the fact that he may not have been entirely straight or cis. Frey says he enjoyed dressing up in women’s clothing; that may just have been a joke or prank on his part, or it may have been more than that.

Toulouse-Lautrec’s interest in sex workers was such that he a actually lived in brothels for a time. Alone, like many of his paintings, is presented as a kind of look-behind-the-scenes of sex work. As the title indicates, the painting shows what the woman is doing on her own, when there are no clients, and no men to see her. Toulouse-Lautrec admired Degas, and this image is perhaps analogous to the older painter’s depictions of ballet-dancers preparing backstage. One discussion I stumbled on online (and now can’t find again) suggested that Alone depicts a woman exhausted after her day; it shows the toll of her labor, her humanity, and her autonomy.

I don’t think that’s exactly wrong, but I don’t think it’s the whole story either. The woman here may be tired, but she’s not just tired. The position of her right hand close to her crotch suggests that she is either preparing to touch herself, or that she has just finished. She believes she is masturbating unobserved, but in fact she is performing, or arranged, so that she is visible and can stimulate not just herself but a (male) observer. The title, Alone is therefore a kind of winking joke; as per the still popular porn trope, the conceit is “look at the kind of naughtiness they get up to when you aren’t there.”

To what extent exactly, though, are men not there? The bed, and the room itself, is cropped dramatically; you can’t see the entire room. You (the male viewer) may not really be there because the room is empty and you are a kind of phantom, imaginary presence. But you also may not really be there because you are in the position of the man who is actually in that space.

That man may be Toulouse-Lautrec himself, since the angle is set low, almost looking up at the bed, which is how the very short Toulouse-Lautrec might have viewed the scene. From that (low) perspective, Alone is actually a portrait of two people—the sex worker on the bed and the painter/client/voyeur, invisible except for the one fact of his unmanly height. The woman is not physically alone; she is “alone” in the sense that she has to (and perhaps has been told to) play with herself without assistance.

Gender in brothels

Alone is, then, not a statement of who is in the picture, but a question or a problem. Is the man there? Or, to put it another way, “Is The Man there?” Is this a painting that is meant to arouse a sense of virility? Or is it a painting about virility’s absence or impotence?

The painting in some ways demonstrates Toulouse-Lautrec’s power, and control. It is Toulouse-Lautrec who posed the model on the bed, who told her where to put her hand, who commanded her to lie there. The expressionist handling of the paint forcibly reminds you of the artist’s dexterity and presence; the yellow and white brush strokes are visible and almost vibrating with energy.

The paint and the painter are an active force in the image; you can feel, and see Toulouse-Lautrec caressing the woman with paint and creating her from paint. She is his—in the sense that he has given her money, arranged her, brought her into being. As the client, he pays her to touch herself; as the painter, his is the hand that touches her. The painting is a virtuoso display of mastery—aesthetic and sexual. Toulouse-Lautrec is the one who is alone; he is the one who’s will determines what is seen, what is done, who experiences pleasure (the woman, the viewer). The sex worker is just a prop to be filled by his genius and his will. She’s just a thing in his dream.

This art star adolescent power fantasy is definitely in the room. But it’s not alone there. Next to it, just out of sight on the bed, is an anxious adolescent disempowerment fantasy.

What sort of man, after all, has to get off by painting a woman? What sort of man has to get off by telling a woman to get herself off? Toulouse-Lautrec’s insistent presence as painter can be seen as mastery, but it can also be seen as a kind of desperation—he protests, or paints, too much. A real man wouldn’t have to substitute a paintbrush for a phallus; a real man wouldn’t need to substitute a woman’s hand for his own. A real man would be standing over her (in various senses), not looking up like a child from the foot of the bed.

The point here isn’t that Toulouse-Lautrec was not a real man. The point is that Toulouse-Lautrec is playing with the idea that he is not a real man. The woman is alone because the painter is not real, not virile, not there. And that implicates the viewer as well; the men looking at the painting cannot touch the woman—they are ghosts, whose desire cannot reach the object of that desire. A viewer must watch the sex worker from Toulouse-Lautrec’s perspective and take on Toulouse-Lautrec’s impotence.

Toulouse-Lautrec did feel like his disability made him less manly at least sometimes. But the impotence here is not entirely unpleasurable. Again, Toulouse-Lautrec had some level of identification with sex workers and perhaps with women. He is disempowered and therefore alienated from the woman on the bed, but the disempowerment also makes him like her, or closer to her in her marginalization. The way her legs are spread awkwardly on the bed and hang down apparently uselessly might recall, or point to, Toulouse-Lautrec’s own legs, which were awkward and disabled. The hand hovering near the crotch is a tease, but also (if those are the painter’s legs) a reminder of the phallus that Toulouse-Lautrec (maybe feels like he) doesn’t have.

If you see the painting as about radical empowerment, then it is a painting of Toulouse-Lautrec alone with his patriarchal power. If the painting is one of radical disempowerment, though, then it could also be seen as a painting of Toulouse-Lautrec, alone, experiencing the self-pleasure of escaping men altogether. The self-portrait he has painted is of the erasure of his own masculinity.

All those men, alone

In Alone, being alone is a crowded place. The painting is a picture of both masterful patriarch and impotent male subject, of both the virile father who owns all the women, and of the envious, exiled son who can only stare and dream. It’s also a picture of the audience—the community of men who exist outside and inside the psyche and the picture. They watch and desire and judge the artist, each other, themselves. A simple picture of a woman alone becomes a kind of patriarchal crisis; men must ask, “Where am I in this image? Who controls her? Who owns her? Who can rise to the occasion? Why am I not there?”

Toulouse-Lautrec’s painting shows that the male crisis of loneliness is a crisis because to be alone is to no longer be a man. Masculinity requires the presence of women to dominate, and the presence of other men so that the domination can be witnessed as evidence of status. Men and women can both be lonely, obviously. But male loneliness is a special cultural problem because in the absence of the validating presence of subordinates and superiors, masculinity vanishes. What’s left, Toulouse-Lautrec suggests ambivalently, is a god or an absence or both. Either way, the site of crisis is also a site of illicit pleasure—which perhaps explains why we are still in that room, watching the same hands move over the same tropes at the behest of the same absent, present patriarch.

As a woman looking at the painting, I don't see any of that! I see a woman who is tired, and relieved that she doesn't have any clients right now to service. She can flop on the bed any old way instead of striking a sexy pose. Maybe she's thinking about masturbating, but she's too tired to be bothered just yet. She's going to have a little rest first. Of course, a man painted this, so maybe your interpretation is close to what Toulouse-Lautrec was thinking.

Love your essay Noah. I think you are right on the mark about lonely Man. Also, not sure what this says about me but when I first looked at the painting I immediately thought it was about masterbation. The hand on the thigh is the focal point of the image.