The Rear of Art

Cumbrae Stewart, Toulouse-Lautrec, disability and queerness

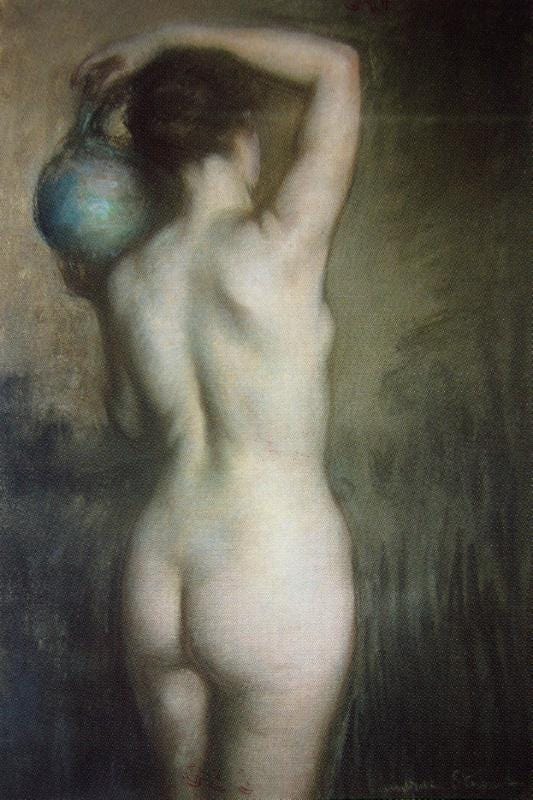

Australian artist Janet Agnes Cumbrae Stewart (1883-1960) is best known for her portraits of female nudes, often painted from behind.

Stewart’s art was quite popular in the 20s—after she moved to England, Queen Mary purchased one of her works—though, per the exhibition catalog of the current exhibit The First Homosexuals, there was some critical confusion about her attitude to her subject. One critic wrote that the paintings were “curiously free of any sex sensationalism.” In contrast the Women’s Prohibition League (NSW) tried to get the work banned as insufficiently puritanical.

Part of the confusion, it seems likely, was that straight critics didn’t know, or didn’t know what to make of the fact, that Cumbrae Stewart was a lesbian. Her paintings self-consciously flirt with and self-consciously defer eroticism; the subjects turn away from the (male) gaze to expose back muscles, buttocks, shoulder blades—eroticizing parts of the body that are androgynous rather than specifically female (Cumbrae Stewart’s significant other, her publicist, Billy Bellairs, was known for her masculine attire.)

Refusing to show certain things is sometimes a way to defuse or avoid overt sexiness. At the same time, though, hiding frontal nudity makes you more aware of frontal nudity, urging you to imagine what you can’t see. The images tease eroticism, even as they tease knowledge and identity, nodding to the classical tradition of male/male love (that urn, those rear ends)—which would have been somewhat more visible in the 1920s—as a way to signal and validate female/female desire. Cumbrae Stewart is painting the closet, and the energy of the images—their humor, their eroticism, the implied motion as the figures refuse to turn and insist on turning—comes from the way the door to the closet swings, now open, now closed, now this way, now that.

When I first saw The Blonde in The First Homosexuals exhibit, the way it focuses on less celebrated bits of the body made me think about the work of critic Tobin Siebers. Siebers writes not about LGBT art, but about disability. In his 2010 book Disability Aesthetics (which I discussed here a while back), Siebers argues that contemporary art of the last 150 years at least has been defined by its rejection of perfect bodies or perfect forms, and an interest in flaws, weakness, non-normativity—or, in Siebers terms, by disability.

To what concept, other than the idea of disability, might be referred modern art’s love affair with misshapen and twisted bodies, stunning variety of human forms, intense representation of traumatic injury and psychological alienation, and unyielding preoccupation with wounds and tormented flesh?

Does this apply to Cumbrae Stewart’s work? The bodies she paints are, after all, young, healthy perfect. In fact, their perfection, and the way they reference classical models, may explain part of why critical attention and enthusiasm has been erratic. Her work seems just a little too close to the neoclassical kitsch promulgated by Nazi dipshits like Arno Brecker.

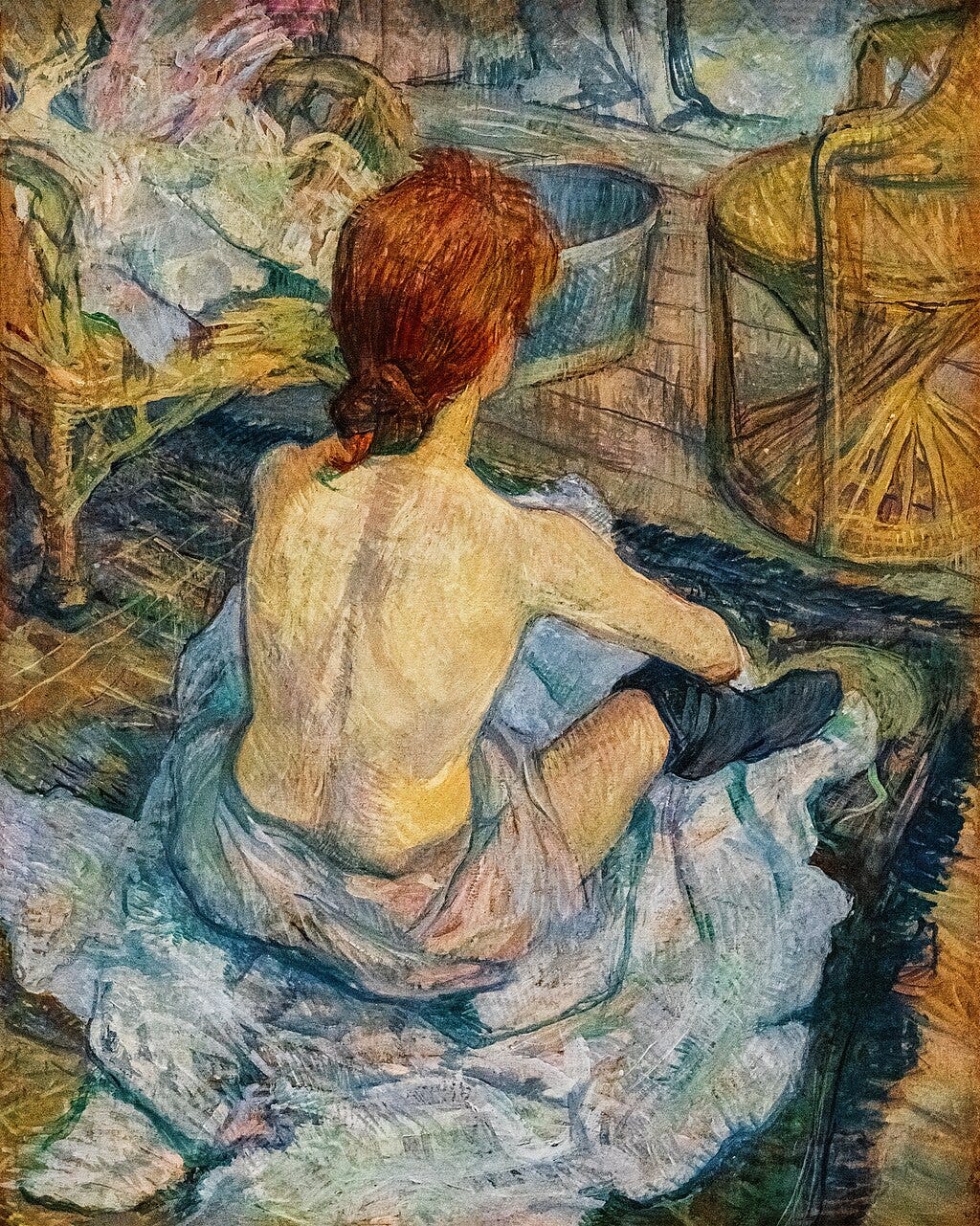

A more flattering, and more apt parallel than Brecker,, though, might be Toulouse-Lautrec’s 1889 painting, La Toilette.

The woman in La Toilette is, like those in Cumbrae Stewart’s paintings, attractive, young, and able-bodied. Also as in Cumbrae Stewart’s paintings, we see her from behind, and the turn away is a provocation. That’s perhaps even more obvious in La Toilette than in Cumbrae Stewart’s nudes, since Toulouse-Lautrec’s image shows a woman whose legs are spread, allowing her to wash her crotch.

Many of Toulouse-Lautrec’s models were sex workers and were meant to be recognized by viewers as sex workers. In this case, the woman is presumably cleaning herself after or before seeing a client. She is someone who is potentially available, and yet in this moment is not, because she is turned away, because she is between clients, because she is a representation and not physically present.

This kind of play with possession/unavailability, visibility/hiddenness is not especially unusual in erotic imagery, whether painting, illustration, photography, or what have you.

But La Toilette is at least arguably doing something a bit different than just soliciting desire —just as the woman herself is, in the picture, doing something different than soliciting desire. The woman’s pose, first of all, is awkward and naturalistic; she seems stiff and somewhat uncomfortable, as she really would be in that position. She’s also thin and even bony; she looks vulnerable, reminding us that people from the lower class often don’t get enough to eat.

Toulouse-Lautrec was disabled himself. He had what was probably a congenital bone disorder; as a result he grew to only 4’11 and had difficulty walking throughout his short life. He also was an alcoholic, and probably had contracted syphilis by the time he painted this picture. Though he was born into the upper nobility, his disability meant he wasn’t able to take his expected place in French society, which is part of why he became an artist, and also why he spent much of his time among the working class and lumpen proletariat, drinking in cabarets and brothels and spaces in between, where he felt, if not accepted, at least in sync with others who were also rejected.

In that context, La Toilette might be seen not just as a painting about desire, but as one about identity. The awkward splayed legs evoke Toulouse-Lautrec’s own infirmity; the effort to clean the genitals nods to Toulouse-Lautrec’s own struggles with venereal disease. Toulouse-Lautrec also (per the biography by Julia Frey) often saw himself as ugly and undesirable. He slept with sex workers in part because he couldn’t have, or did not believe he could have, a relationship with a woman of his own (very high) class.

With Toulouse-Lautrec’s biography in mind, you could argue that what the woman is hiding here, or what she has turned away to conceal, is Toulouse-Lautrec’s lack or impotence. Toulouse-Lautrec is everywhere in the painting—the visible brushstrokes touch the sheet, the woman’s leg, the chair, so everything seems to almost vibrate with the intensity of his observation. And yet, that presence emphasizes his inability—to touch, to stand, to be lover rather than observer.

Cumbrae Stewart’s perfected finish, graceful poses, and neutral, non-specific mise en scène don’t feel ambivalent or unsettled in the way that Toulouse-Lautrec’s painting does. But I think the comparison with La Toilette nonetheless underlines the way that the closet creates not just a queer gaze, but a queer body that is odd, altered, not straightforward. Toulouse-Lautrec’s model is turned from him to hide his own face; just so Cumbrae Stewart’s models are turned away to conceal—or, arguably, to reveal concealment. The lesbian gaze is not the male gaze, and so the lesbian body, shaped by that gaze, is not the normative body either, inasmuch as it is androgynous, turned, hidden even as it is exposed.

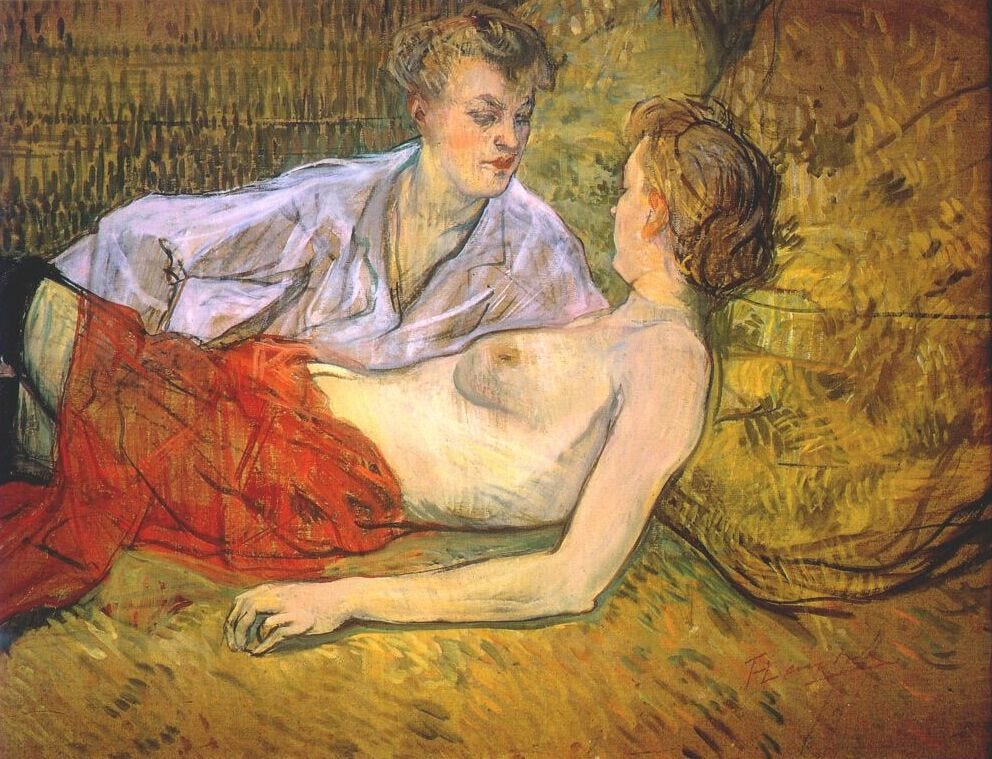

In this sense, “modern art’s love affair with misshapen and twisted bodies [and a] stunning variety of human forms” is a love affair not just with disability, but with queerness. Or to put it another way, representations of disability and queerness inform, speak to, and blur into one another—as in Toulouse-Lautrec’s images of lesbian couples, which can be viewed as lascivious, but also as indicating his own identification as a disabled man with other marginalized people.

The Trump administration’s ongoing effort to stamp out decadent art, like similar past Republican anti-art initiatives, is based on a hatred of both different desires and different bodies. The fascist cult of “health” excludes both queer people and the disabled, all of whom are relegated to a purgatory beyond imagination in the name of a eugenically purified body and mind. Only the fit are to be acknowledged and visualized. The rest are to be turned away from public visibility and from life. And yet, as Toulouse-Lautrec and Cumbrae-Stewart show, or don’t show, that turning away is also art, and will not be turned away.

I appreciate your writing so much. Thank you for the opportunity to consider images and ideas that I otherwise would have missed. I wonder if in the turning away from the (male) gaze, these paintings suggest women having a life outside of it, a personal self. I know next to nothing about art, but that’s one thing I see.

I hope that like past anti-art initiatives, the current one makes us all more aware of artists we otherwise might not have heard of. Robert Maplethorpe became a household name because of the outrage over his photography. I hope many other artists become famous this time around. Let’s make censorship work by highlighting the work of censored artists.