Can Superheroes Do Without Prisons?

Invincible Says…Sort of!

Most superheroes are in the business of foiling criminals and then putting them in jail. With the occasional arguable exception of a Suicide Squad film here or there, superheroes are usually on the side of the cops and the prison guards. They don’t question whether prison, or mass incarceration, is a good idea.

One odd exception which tests the rule is the Robert Kirkman/Cory WalkerRyan Ottley comic Invincible. The first series arc is about how superteen Mark Grayson discovers that his superdad Omniman is not in fact the world’s greatet superhero and good guy. Instead, Omniman is a malevolent alien Viltrumite bent on world conquest. In his final battle with Mark he murders hundreds of thousands, and then flies off into space.

That’s the best known plot point, and takes you through the first season of the Amazon Prime adaptation. But it’s after that that the series starts to get obsessed with imprisonment and reform.

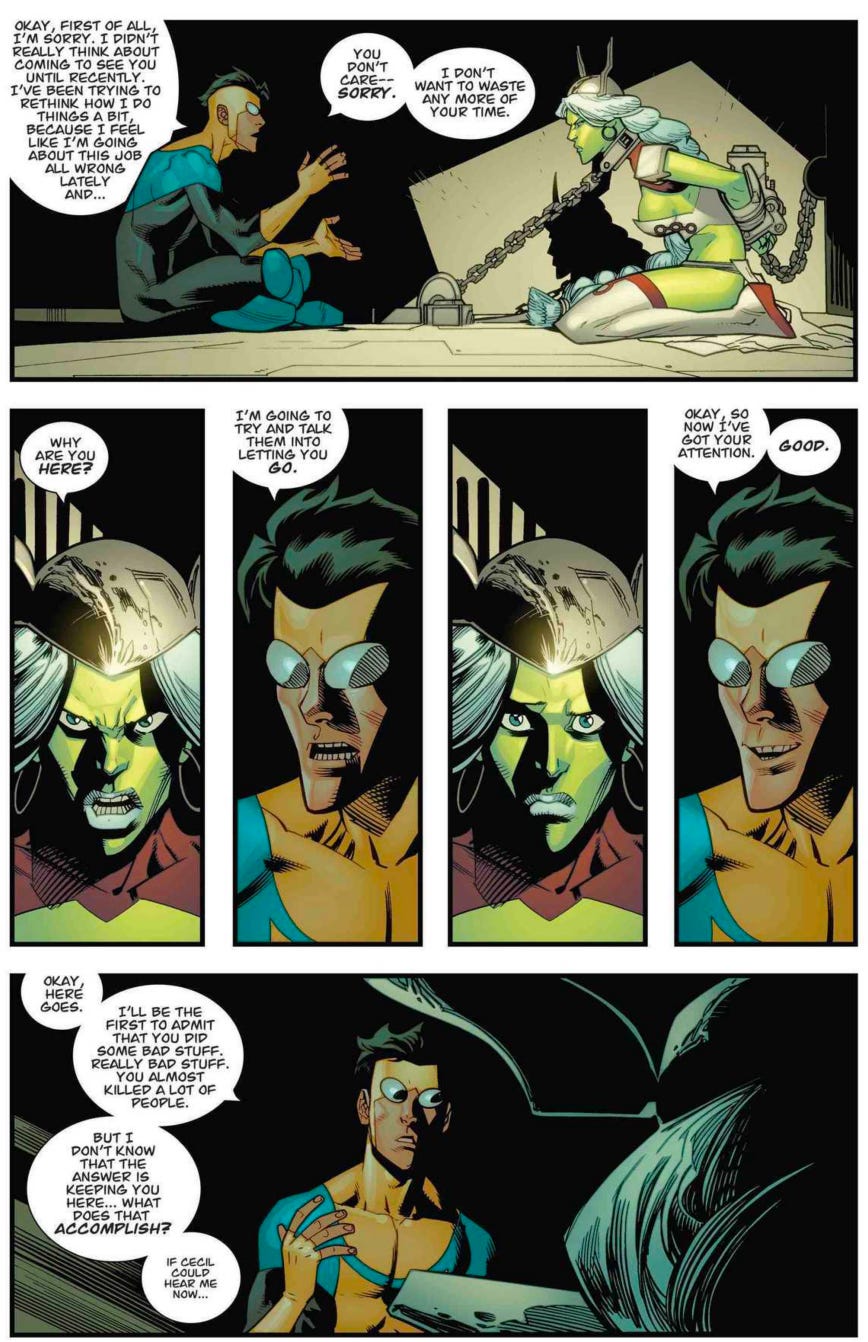

Omniman, it turns out, is going through a crisis of conscience. The next time Mark meets him, he’s apologetic, and wants to help protect earth from the Viltrumite empire.

That’s not the only rehabilitation either. Virtually every major villain in the comic eventually ends up working with Mark in some capacity.

Mark captures a mad scientist who kills people and then reanimates their corpses as supersoldiers. Instead of imprisoning him, the government recruits him to make an army for them in case the Viltrumites attack again. A super-advanced dinosaur-man, Dinosaurus, keeps causing catastrophes which kill thousands now in order to save the earth from environmental degradation in the future. Mark decides the dinosaur guys motives are good, breaks him out of captivity, and teams up with him.

The treatment of sexual violence in the comic is even more striking. A psychotic Viltrumite woman violently rapes Mark. He is as you’d expect traumatized, and partially as a result does not tell anyone. The Viltrumite woman goes on to marry on earth, and eventually decides that what she did was wrong. She is never formally punished, except that she, like Mark, has to live with what she did.

There are numerous other examples as well. Villains in Invincible rarely stay villains, and heroes often do villainous things. The comic rejects the usual superhero absolutes of good/evil, and so also rejects the logic of incarceration. When people do wrong, Kirkman usually asks not, “How can they be punished?” but “What good can they do to redress those wrongs?” It’s a restorative justice approach. Within limits.

Those limits have to do with how restorative justice is applied, and by who. In Invincible, the decisions about how to treat villains are all top down. The government decides to free that mad scientist; Invincible frees Dinosaurus. Justice happens without democratic process and without community involvement or engagement. The state and the powerful impose noncarceral solutions.

In the real world, obviously, guards aren’t usually the ones demonstrating to close down prisons. By making the government and Mark the leaders of justice reform , Kirkman distorts much of the debate about mass incarceration and policing in the real world.

As one obvious example, Kirkman’s engagement with issues of policing and rehabilitation almost entirely ignores racism. In the real world, the most telling and thoughtful analyses of the problems with our criminal justice system have generally come from antiracist thinkers like Ida B. Wells and Mariame Kaba. These writers point out that America’s justice system is shaped by prejudice, inequities, exploitation, and violence directed at marginalized people, and especially at Black people. It’s those at the business end of that violence who are in the best position to critique it, and to imagine other kinds of justice.

Part of that critique is of hierarchy itself; police and prisons are used to control potential dissidents and to silence those who demand a more equitable system. “When you say, ‘What would we do without prisons?’Mariame Kaba writes, “what you are really saying is: ‘What would we do without civil death, exploitation, and state-sanctioned violence?’”

Kirkman’s new idea of justice isn’t about empowering people, though. Instead it’s about the empowerment of one super someone. Galactic justice and mercy come about because of the eventual wise rule of Mark, who it turns out has a hereditary claim to Viltrumite leadership. Justice in Invincible doesn’t mean reducing power differentials. It means finding a more just, and ever more powerful, ruler.

Invincible believes that law enforcement is a narrow, inadequate form of justice for a truly super society. But while it breaks some bars, it’s still boxed in by the genre’s reliance on vast power differentials and singular invincible heroes. Mark opens a lot of cages, but he’s presented as the only guy who can open them. For the rest of us, that isn’t exactly freedom.

::...while it breaks some bars, [INVINCIBLE]’s still boxed in by the genre’s reliance on vast power differentials and singular invincible heroes.::

Except that's not a bug, it's a feature of superhero comics—even superhero comics that try to interrogate what it means to be a superhero. Every superhero or supervillain is an extraordinary being in one fashion or another, which means that it's incapable of speaking to ordinary prisons and prisoners.

You COULD use people with superpowers as a metaphor for a minority who's a victim of prejudice—that's what The X-Men became beginning with Chris Claremont, and Frank Miller's THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS has the U.S. Government outlawing superheroes except for Superman and a handful of others they use surreptitiously as "secret weapons". But even there you run into extraordinary beings who are going to be treated differently than somebody whose socioeconomically disadvantaged.

Unqualified to respond on so many levels but fascinated by the mirror this holds up to the dynamics of who we are.