Emily Dickinson and Toulouse-Lautrec Look At Nothing

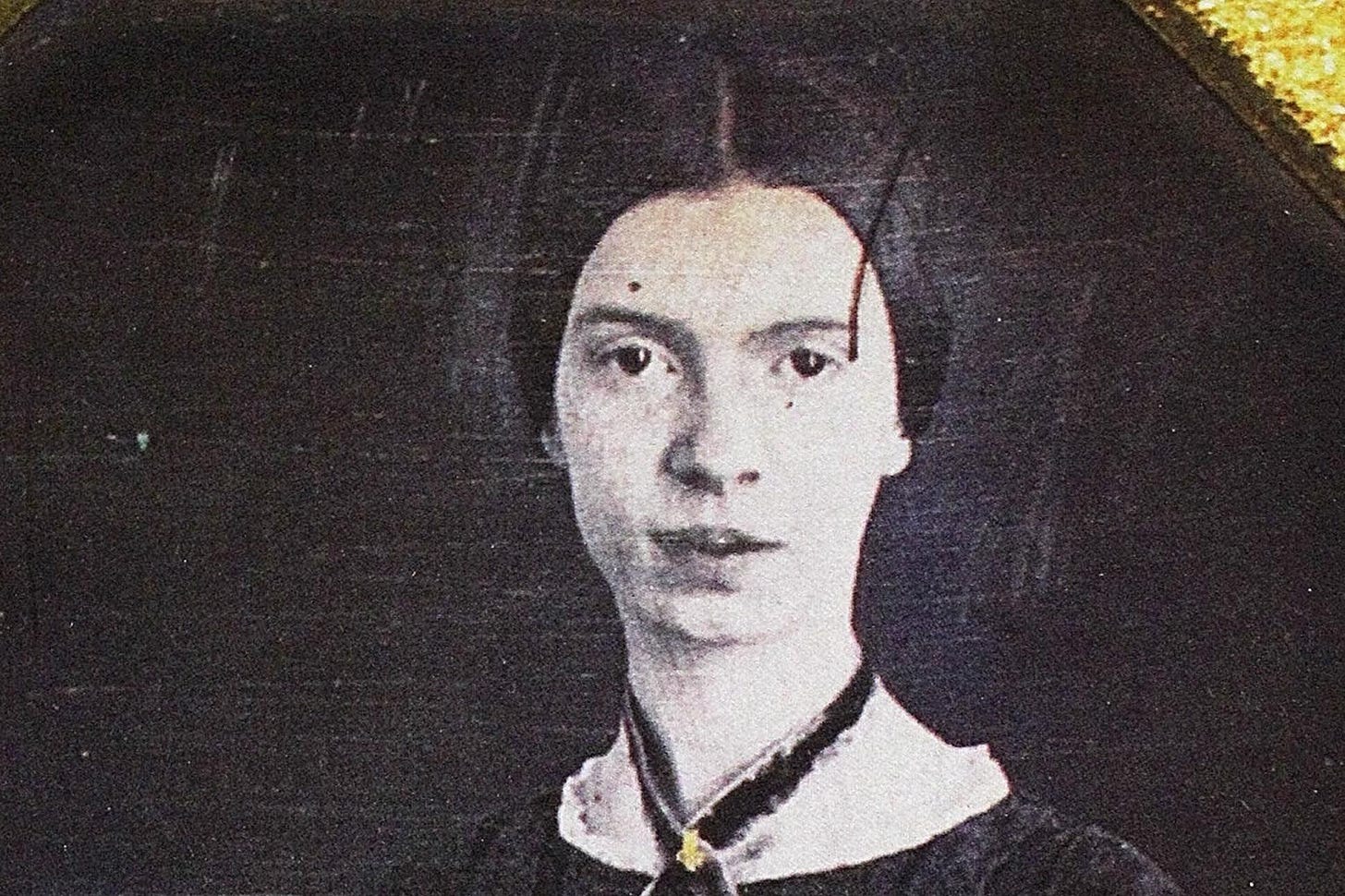

A reading of "Like Eyes that looked on Wastes"

Emily Dickinson’s poems can be famously difficult to parse. I’ve been turning this one over for weeks.

Like Eyes that looked on Wastes –

Incredulous of Ought

But Blank – and steady Wilderness –

Diversified by Night –

Just Infinites of Nought –

As far as it could see –

So looked the face I looked opon –

So looked itself – on Me –

I offered it no Help –

Because the Cause was Mine –

The Misery a Compact

As hopeless – as divine –

Neither – would be absolved –

Neither would be a Queen

Without the Other – Therefore –

We perish – tho’ We reign –

It’s a riddling, bleak little poem, in which Dickinson’s omnipresent dashes separate stuttering, broken glimpses of a repetitive internal and external wasteland, fragmented and absent—a quintessentially modern poem of shattered selves and shattered meaning, which seems like it should have been written fifty years after its composition date of 1863.

The fragmentation and absence create, or are defined by, the gaps in meaning which the poem demands the reader try to see, despite the assertion that there is nothing to be seen. Whose eyes are looking? What do they see? Who is looking back?

The Dickinson critics at the Prowling Bee provide a good starting place to try to find some answers.The poem they say:

can be read as either between two lovers OR as between the self and the self’s reflection. Is this on purpose? I think so, or at least I think it is likely she wrote it with both in mind.

The lover in question here is probably Sue Dickinson, Emily’s sister-in-law. Emily and Sue had a close, romantic, and possibly physical lesbian relationship before Sue—an orphan in financial straits—married Emily’s brother Austin.

—

If you find my long, bizarre posts about art valuable, it’s a good time to support me! I’m having a 40% off sale today. It’s $50/year, $5/month.Please consider becoming a subscriber so I can continue to write!

—

Morisot and the Mirror Stage

Before we work through that interpretation further, though, I think there’s another meaning Dickinson is playing with or thinking about here. It solidified for me when I was reading Megan O’Grady’s forthcoming book in which she discusses this wonderful painting by French painter Berthe Morisot.

Woman At Her Toilette, completed in the 1870s, shows Morisot in a fabulous gown, preparing to go out. It is in the tradition of voyeuristic paintings by men for men in which women’s vanity and self-regard becomes an excuse/pretense for men’s erotic perusal of female bodies on display.

This painting is different though. Morisot is not in a state of undress, and her form—and particularly her reflection—dissolves into the tactility of the frankly sensual brushwork, all luxurious creams and pinks. The self-fashioning here is not vanity, but tactile mastery. Morisot making herself up to go out is a metaphor for Morisot as painter making her image, or vice-versa. The mirror is Morisot’s tool, but it is also Morisot herself, since, as an artist, she sees and forms her own image.

In this context, “So looked the face I looked opon –/So looked itself – on Me –” could be Dickinson looking in the mirror opon (on/upon/openly at) her reflection; it could be Dickinson looking at her lover. But it’s also Dickinson looking on the poem she is creating, which also looks on the self it is creating or from which it springs. Dickinson makes the poem which is her, and the poem makes Dickinson, which is also her.

Dickinson, like Morisot, is the artist as mirror calling herself into being. This is precisely how Lacan describes or conceptualizes the mirror stage—the moment when the child recognizes itself as its reflection.

This event [the child seeing itself in the mirror] can take place…from the age of six months, and its repetition has often made me reflect upon the startling spectacle of the infant in front of the mirror. Unable as yet to walk, or even to stand up, and held tightly as he is by some support human or artificial…he nevertheless overcomes, in a flutter of jubilant activity, the obstructions of his support, and, fixing his attitude in a slightly leaning-forward position, in order to hold it in his gaze, brings back an instantaneous aspect of the image. [translation by Alan Sheridan]

As I’ve discussed before:

Some pop commentary treats the mirror stage as…well, a stage, a developmental milestone. The child recognizes his true self, which makes him “jubilant.” Recognizing himself as himself, the child knows himself…

But Lacan’s original, opaque prose is a good bit more ambiguous than this cheerful narrative of progress. He says that the infant, when he looks in a mirror, “anticipates in a mirage the maturation of his power.” That is, the child sees not who he is, but who he imagines himself becoming.

More, the moment of recognition for Lacan fuses the ego “with the statue in which man projects himself, with the phantoms that dominate him, or with the automaton in which, in an ambiguous relation, the world of his own making tends to find completion.”

What that means (maybe) is that the child looking in the mirror creates a false self—a statue, a phantom, an automaton. The mirror stage is not the moment when the child recognizes its true identity; instead, it’s a metaphor for the process, untethered from sequence or time, whereby the self invents a future self, complete with past, present future, and a story of joyfully discovering the self.

Morisot’s self-creation in the mirror captures the exuberance that Lacan attributes to the mirror stage—the recognition of autonomy, identity, and power which goes along with self-creation. But Dickinson I think is tuning more into the anxiety that attends a self as a “mirage.” If you create yourself, if your true self is the act of creating the self, then what are you but endless empty reflections: “Just Infinities of Nought”?

Toulouse-Lautrec and The Nothing In The Mirror

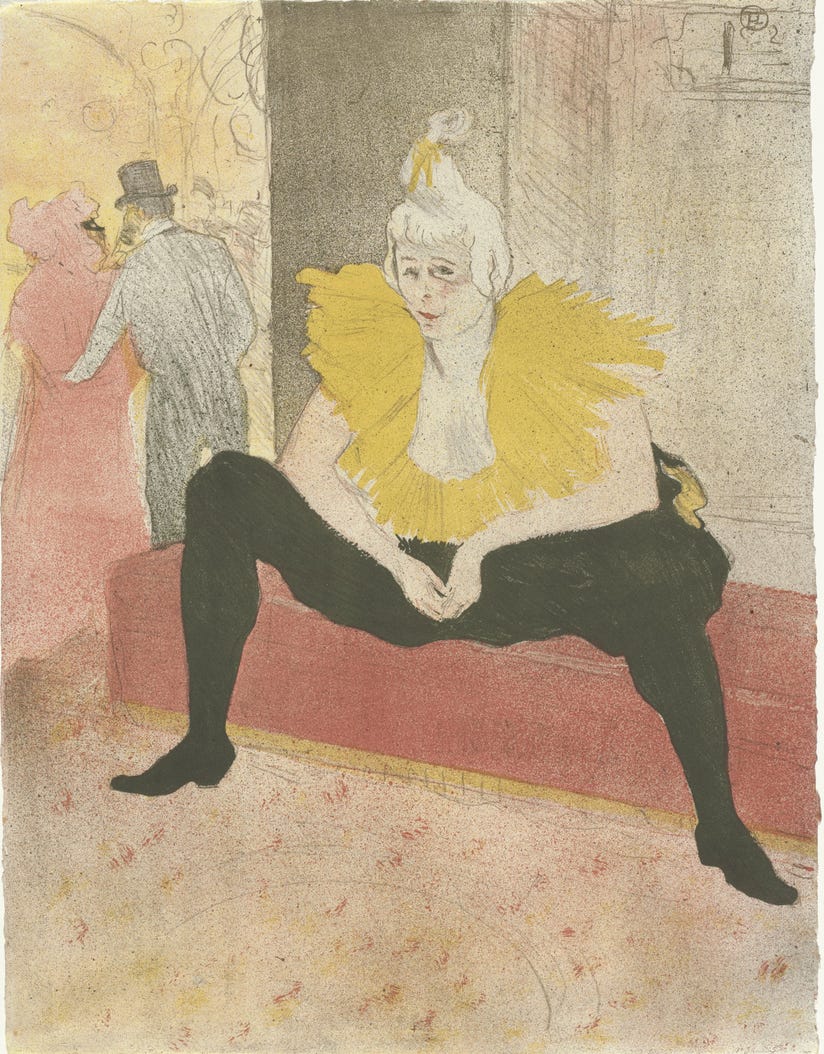

It might be useful to look at the work of an artist whose work reflects (as it were) some of Dickinson’s anxieties. Here is Toulouse-Lautrec’s Mademoiselle Cha-u-kao, The Seated Clowness.

At first, the cosmopolitan, decadent Lautrec, the chronicler of Parisian nightlife, might seem an odd point of comparison with the rural, religious, Dickinson who wrote about flowers and bees and her interior life. But whatever their differences, it’s nonetheless the case that both poem and painting are ambivalent portraits of ambiguously lesbian women with whom the artists were obsessed.

Toulouse-Lautrec is a man, of course—but also maybe not so “of course.” As the biography by Julia Frey discusses, and as I’ve written about here, Toulouse-Lautrec’s relationship with masculinity was fraught. He had a congenital condition that stunted the growth of his legs, and he seems to have seen himself throughout his life as undesirable. He also cross-dressed; it’s impossible to know if he did so simply as a joke, or if it was a muted expression of a queer or non-cis gender identity.

In any case, Toulouse-Lautrec was fascinated with lesbian prostitutes, because he found them desirable and also perhaps because he saw himself as exiled by his disability, and so identified with their marginalized status.

The artist’s complicated relationship with his subjects is visible in this lithograph of Cha-u-kao, a performer at the Moulin Rouge. Cha-u-kao appears in many of Toulouse-Lautrec’s works, often in intimate scenes with her partner Gabrielle. Here, however, Cha-u-kao is resting on a bench, legs spread, smiling rakishly at the painter.

Cha-u-kao’s pose emphasizes both sexual desirability and gender nonconformity. Her dramatic yellow ruff frames her breasts, and her hands are clasped directly in front of her crotch. Her legs are so wide open they look almost uncomfortable or parodic. The outsized invitation is titillating, but also suggests a masculine aggression and swagger. As a woman performer who stands (or sits) outside conventional domestic gender roles, Cha-u-kao’s unfemininity sprawls profligately: prostitute, lesbian, object, subject, woman, man.

Toulouse-Lautrec creates an image of a disordered, desirable self because he wants it for himself. That can mean sex. But it can also mean identity. Notice that Cha-u-kao is staring directly at the artist; he is at her eye-level even when she sits, obliquely emphasizing his short stature. In addition, she is arranged in a masculine pose that Toulouse-Lautrec himself could not achieve, given the limited mobility of his legs. Lacan might say that this is an image of what Toulouse-Lautrec lacks–or he might say that Cha-u-kao is displaying, between her legs, in her clutched hands, the absent phallus that Toulouse-Lautrec does not have. The image’s vivid character and liveliness, its mastery and power, create a self for the artist which mocks the artist’s self.

Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithograph is a queer image because it depicts a subject, and an artist, whose relationship to sexuality and gender are (at least potentially) non-normative. But it’s also a queer image because its construction of self and identity isn’t straight or straightforward. Morisot’s painting is about how she makes herself, as artist and woman. Toulouse-Lautrec’s is how he makes someone who is not him, as (maybe not an?) artist and (maybe not a?) man.

Looking at Emily Again

So let’s return to Dickinson after that detour through French art. If there are parallels with Morisot and Toulouse-Laurtrec (and obviously I think there are), then we might see the poem as Dickinson both celebrating and painfully confronting the limits of her powers of self-fashioning as an artist and as a queer woman. What she sees in the mirror is the poet her genius has made, and the woman she cannot quite make conform to her society’s vision of proper desire and domesticity.

Like Eyes that looked on Wastes –

Incredulous of Ought

But Blank – and steady Wilderness –

Diversified by Night –

“Like eyes that looked on Wastes” begins the poem with a metaphor that has no referent. The Prowling Bee suggests that the eyes are “like eyes” because they’re the eyes in the mirror. But a poem that begins in metaphor and has no outlet could also be referring (mirror-like) to itself. The thing that is “Like Eyes” is the poem, and the “Wastes” it looks on could mean the person that created those wastes—the not self that calls itself into being.

Dickinson is a self in and of the poem; she is “looking” at her own art, which is also her self. And that self in turn is what Sue has made of her; a “Blank” a “Wilderness –/ Diversified by Night.” Or, alternately (and simultaneously) what Dickinson has made is an image of Sue, which is nothing, and therefore makes of Dickinson a nothing—a thing in which she (“Incredulous”) does not believe.

Just Infinites of Nought –

As far as it could see –

So looked the face I looked opon –

So looked itself – on Me –

In the second stanza, Dickinson’s eyes/not eyes look at “Infinities of Nought”— a phrase which plays with the paradox of an empty plenitude. The poem could be talking about simply the vastness of nothingness that Dickinson feels without Sue. But it also could be playing with the power of mirrors—and poems—to create illusions, or lacks. As an artist, Dickinson brings nothing into being, but the being still is nothing, just as she can imagine herself with Sue, but Sue is still not there.

The face that looks is referred to with the pronoun “it”. The Prowling Bee suggests that the neuter term is used to signal that the referent is the mirror, which of course is neither he nor she. It could also refer to the poem.

But degendering mirror/poem also degenders those who appear in the degendered space—which in this case means both Dickinson and Sue. The lack of gender could refer to the failure of the relationship. It could also be a reflection on the way that that relationship by normative terms would be seen as a failure or a lack or absence; Sue plus Dickinson is a gendered equation that makes no sense and must be turned into nothing.

In that context, the neologism, “opon” could be seen as a kind of failure of language and meaning; the poem is attempting to create Dickinson and Sue, but stutters into nonsense. Similarly, “So looked itself – on Me –” is the non-gendered self in the mirror looking at Dickinson, but it is also the creation, or imposition of the disordered romance and gender upon (or opon) Dickinson. Dickinson creates herself in the poem, but the poem has no “her” because what she wants cannot be fulfilled or expressed. In creating a queer self, she becomes queer, since the self she creates is her—but there aren’t words to express queerness or talk about it, in her self or in her poem.

I offered it no Help –

Because the Cause was Mine –

The Misery a Compact

As hopeless – as divine –

The Prowling Bee points out that “Cause” can have two meanings here; Dickinson can be saying that she caused the harm, and/or she can be saying that she cannot help because the cause that requires help is hers. As in a mirror or a poem, she has created the other self, and she can’t aid that other self both because it is her creation and because the self she has created is her—or to put it another way, she can’t help herself.

One of the comments at the Prowling Bee suggested that the “compact” here could be the agreement between Sue and Emily to be lovers and lifetime companions—a compact that Sue broke, but to which Emily, to her misery, still treats as true.

The compact here could also be, though, the creation of the poem, which is the compact that creates both Sue and Emily, self and image. The compact is “As hopeless – as divine – ” because creation is God-like, and because that creation is ultimately empty or broken. The creation of the self is both a triumph and a failure—which Dickinson may be contrasting with God’s creation or comparing to it (her relationship to religious faith is an open question throughout her poems.)

Neither – would be absolved –

Neither would be a Queen

Without the Other – Therefore –

We perish – tho’ We reign –

The final stanza is a crescendo of conundrum. The claim that neither “would be absolved” doesn’t seem to quite make sense of Sue, who does seem to have forsworn her relationship with Emily, at least to the extent of entering a conventional marriage. And it’s difficult to see how a mirror could be “absolved”, or how it could be a “Queen” for that matter.

I’m not sure I have any key here. But I do think that it adds at least a kind of sense if you read the last stanza as self-reflecting. The poem, in this case, could refer to both Dickinson and her creation, the poem which also creates Dickinson. Dickinson’s identity and her power depend on her making of herself; the self-fashioning she does through poetry, and, perhaps, through loving Sue. But these selves rely on others that dissipate or disintegrate—because Sue left; because queer identity lacks social affirmation (note that in Lacan the “Big Other” is the group of social norms that structure the self); because human self-image rests on a mirror that isn’t there.

Why does the “we” both “perish” and “reign”? Perhaps because when the self is nothing, the collapse into nothing is a kind of victory of the self? Toulouse-Lautrec’s portrait of Cha-u-kao is an apotheosis of nothingness—a perverse triumph built on his own self-negation. Dickinson is arguably doing something similar; the poem is after all a tour-de-force of absence, which negates Dickinson’s love, her gender, and her self in a queer assertion of her own infinite nothingness.

Without Sue—without the absence of Sue—without the wrong self that is Emily’s desire for Sue—the pome would not exist, and neither would this particular Emily who created the poem and is created by it. It is only by being this nothing that this poem can take its place as royalty.

This is fascinating. Thank you.

I like your exegesis but I read the opening lines as a reference to the explorer who gazes upon “wastes” and “wilderness” and is stricken by the emptiness. The poet then confronts her face, and it confronts her back in a mirror, real or metaphorical, like the explorer on the edge of the vast, empty landscape. Explorers’ accounts of strange lands were popular and show up in much 18th and 18th literature which Dickinson may have read. From there, I agree with what you propose the poem shows of the poet’s conflicted self.