How Women Can Have At Least Some Of it

Economist Corinne Low talks about women’s choices and constraints

Wharton economist Corinne Low’s new book Having It All: What Data Tells Us About Women’s Lives and Getting the Most Out of Yours deliberately defies the self-help zeitgeist. In general, books about gender these days are supposed to focus on manly men and how they can optimize manning. Self-help books, meanwhile, are supposed to provide you with one neat life hack to…well, have it all.

Low refuses to focus on men; also she refuses to provide one cool life hack. Instead, Having It All is a sober, data-driven assessment of the limits women face in a patriarchy which discriminates against them at work and places the largest burdens of marriage and children squarely on their backs at home.

That doesn’t mean that the book is all gloom and doom though. On the contrary, Low believes that knowing the challenges they face can help women make better choices and create better lives for themselves. If you’re told you can have it all, you start to feel desperate when you don’t. If you’re told, more honestly, that you face a series of very specific barriers, you can better plan for how to scale the ones you want to get over, and maybe just avoid the ones that aren’t worth the hassle. Living your best life can feel like an unmanageable chore; better, perhaps, to live a better one.

I spoke to Low last week about who cleans the house, pros and cons of divorce, the pros and cons of paid family leave, and why her book sparked a mini moral panic. The interview has been edited for length and clarity. Images are courtesy of Corinne. (And you can follow her on substack.)

—

I’m able to interview amazing and insightful people like Corinne because of your support! So if you find features like this valuable, please consider becoming a paid contributor. I’m having a sale today; it’s 40% off, $30/year.

Noah Berlatsky: Your book Having It All, is in conversation with Sheryl Standberg and the idea of “leaning in” at work. What do you see as the problem with Standberg’s approach, and what are you recommending or arguing for instead?

Corinne Low: The “lean in” idea presumes that a person’s objective function is maximizing career success—you lean into the corporate world and maximize your career growth.

And I understand the temptation to want that because—you know, I start my book talking about this chart from a Claudia Goldin paper that shows right after graduating with an MBA from Chicago Booth, men and women’s earnings are similar. But 12 years out, the 90th percentile of female earnings is the same as the male mean. And so I understand that when you look at that chart, you think, “This is so devastating!” You think we need women to be doing something different.

And so I understand the urge to create a call to action. But for me, that chart says—well, that’s the 90th percentile of women. That’s the women who are leaning in. They have grit. They’re doing everything that they can and they’re being failed by the system.

And so the last thing I want to do is yell at them that they need to try harder. I look at that and say, we need to give people permission to navigate those systemic forces in whatever way works for them, doing whatever makes you happiest. Because we can’t just keep trying harder in a system that’s failing us, or in a system where women are at such a disadvantage compared to their male colleagues. Women just have fewer hours in the day because they don’t have the same support at home as men do. I feel like the rallying cry to “lean in” misses the point. And the point is that as a woman working harder might not get you a better outcome.

What we need to do is to figure out how to navigate around or eliminate some of these constraints. Or reframe goals in terms of,—how do I get what I want out of my career instead of just achieving maximum success according to somebody else’s definition.

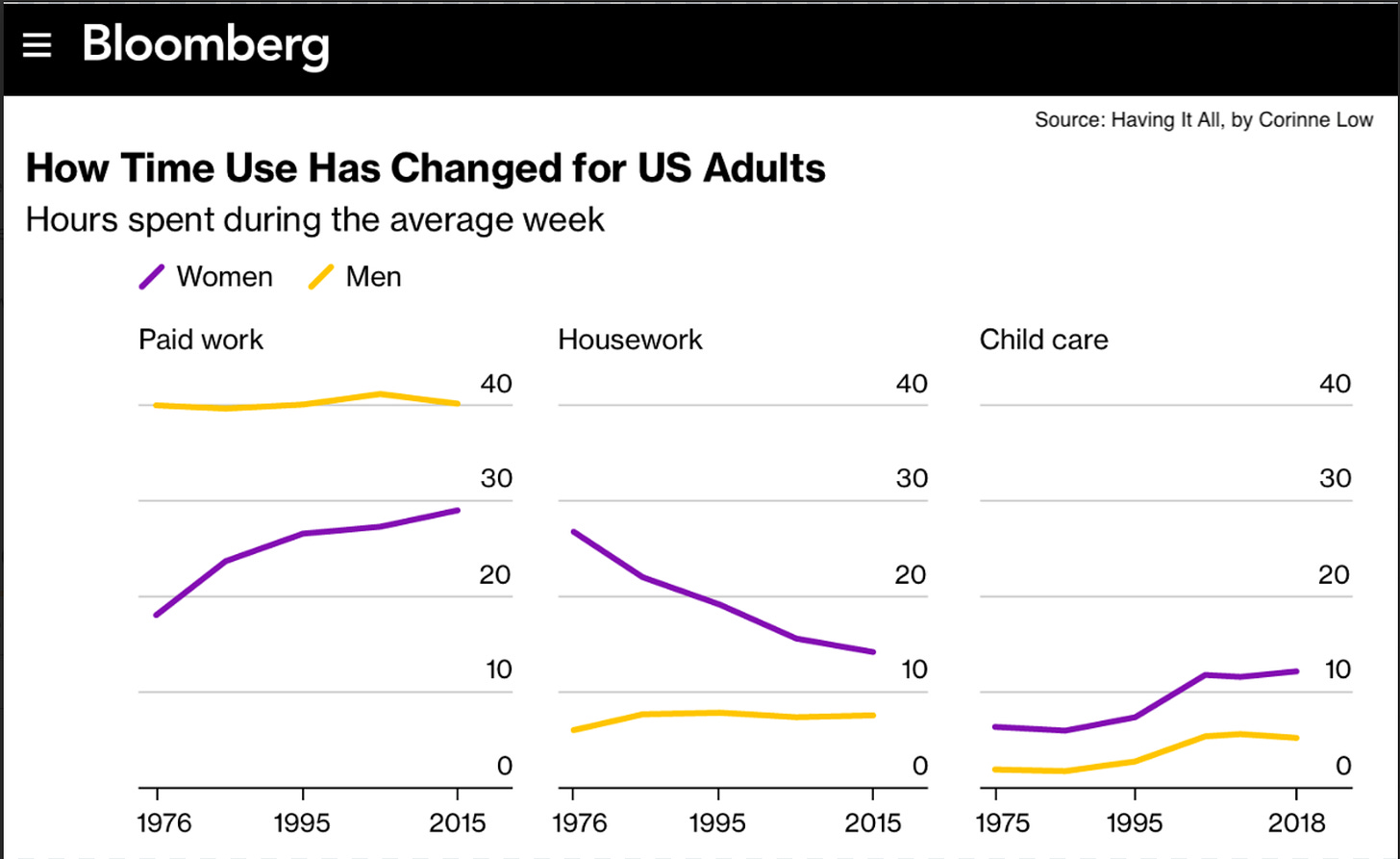

You said that women don’t have as much support. Is that because men aren’t doing as much work around the home and aren’t doing as much childcare?

Yes. With childcare, this is one area where men’s time caring for children actually has increased compared to the past. But because total time caring for children has increased so much, the gender gap in the household has gotten wider instead of narrower.

And then with housework, men’s time hasn’t increased at all. Even when a woman is the primary breadwinner, she still does twice as much cooking and cleaning as her lower earning male partner. So if you compare a very high-powered woman at work to her male colleague in that same position, he is doing much less at home. And that means that he has more hours to invest in career growth.

I just read Scott Galloway’s Notes On Being A Man. And it’s part of this relentless argument in the media that there is a crisis of masculinity, that men are falling behind. But your data suggests that women are still disadvantaged in most of the ways that they have always been. Men do less housework at home, men sexually harass women at work and discriminate in hiring and promotion. So, from your perspective is this “crisis of masculinity” just a way to justify backlash?

I think the reality is that I do think that men are struggling. And I don’t know if that’s more or less than women. I think lots of people are struggling.

But I think men who are struggling and feel alienated, you look at the data, how much more time people spend alone, how much less time they spend with friends, marriage rates declining, potentially fertility rates declining, right? My issue with this is that I think it’s counterproductive to recenter the conversation around men in order to solve that.

Because I think the reason that they’re struggling is their inability to connect with women to form strong and healthy families in the new realities of the situation where women’s time at work is as productive as men’s time at work.

That’s the underlying economic shift. There are all the pernicious things that happen in our economy to make it unequal and to kneecap the lower middle class, right? That is eroding men’s earning power. But along with that, you have this gender revolution that’s just happening at work and hasn’t happened at home, where women are able to earn the same amount as men at work, because in a knowledge-based economy, as opposed to a physical labor-based economy, women are equally competitive.

So now you have women able to be equally competitive at work, they’re able to bring a paycheck to the table. But men’s gender roles haven’t changed at home. And so men don’t know how to show up differently in the household. They’re affected by these very negative economic changes of being laid off, or that a manufacturing job doesn’t support a family anymore, or that the gig economy doesn’t come with benefits.

But in addition, when you’re affected by the negative economic changes, it is hard to find marriage and partnership, because you’re not bringing enough to the table financially, and you haven’t learned to bring something to the table in other domains. And that’s what I see in the data, it almost to me looks like men are stuck when I see couples where they’re both hourly workers and her wage are more than twice his wage, but he’s still working more hours than she is. And she’s still doing twice the home production, even though her wage is more than twice his hourly wage, and they could adjust their hours because they’re in these hourly jobs.

For example, he’s an Uber driver, and she’s a nurse. And if he would pick the kids up from daycare so she could pick up an extra shift as a nurse, the whole household would be richer. But he’s stuck in this gender role, right?

So I think that men are struggling, I think they are alienated by that. I don’t think that they know what to do. But my problem with Scott Galloway’s message, and I think he’s a smart guy, he’s diagnosing the problem correctly, but I think the solution is exactly wrong. Because saying, oh, poor men, let’s re-center the conversation on their feelings, this is the point, that what they need to feel less alienated is to learn to be in community with women, to be in partnership with women, to be a productive part of society, rather than being able to kind of bend society to their will.

One of the things Galloway talks about in the book is about dumping his first wife, basically because he wanted to go sleep with other women. So they divorced.

And in your book you talk about how no-fault divorce has allowed women to get out of abusive marriages. But women have less leverage also to force men to pay when they want to do what Galloway did and unilaterally dissolve the marriage.

Yeah, absolutely. In the book I talk about the fact that a big part of the explanation for women’s increase in labor supply is that the bottom fell out of the marriage economy. And so, specializing in home production is a really bad deal for women right now. Tha’s also what’s missed in this tradwife discourse of like, “oh, we can just go back to these more traditional gender roles,” is that those roles are extremely economically precarious for women. We no longer have a legal structure that supports that.

Could you explain why that is?

We went from mutual consent to divorce to unilateral consent to divorce. With mutual consent to divorce, it’s like a business partnership where if you want to dissolve the partnership, you have to buy out your business partner, which is what allows you to do risky things like say, oh, I’m going to share my IP with you because you can’t just then walk away with it.

And that’s the same thing in a marriage contract. Traditionally, it was a mutual consent to dissolve the partnership. So, if somebody wanted to leave their wife to go sleep with other women, they had to buy their wife out.

There’s a scene in Mad Men that I love that spells this out where Roger Sterling says to his wife, you know, I want a divorce. And she says, I know, but it’s going to cost you. And he pulls out his checkbook, and he writes her a check to get her consent so that she will go in front of the judge and say, this is mutual, right?

That is insurance it’s saying that you can do something risky, like specialize in raising the children and taking care of the house and not invest in your own human capital because you’re insured that you’re going to benefit from the spoils of your labor that are then going into his career in case the relationship dissolves.

Once you have unilateral consent to divorce, then either person can just walk away. And yes, you have to divide assets. That means that that person who invested in the home and the kids is going to be left with a much lower income if the divorce happens than the person who invested in their own career.

The couples that have assets have something that I call a collateralized marriage where they still have some kind of insurance because at least the assets, the house or the savings account, are going to be divided. But couples that are in debt or couples that don’t have assets, they have very little that is going to make the other person [that is, the person focusing on domestic labor] whole. Because child support is for a very limited time and it’s very limited in scope. It doesn’t make up the benefits of actually fully sharing income from one person’s career.

Usually the biggest asset formed in a marriage is the husband’s career and that’s what he walks out the door with. It’s his earning power from there on out because if you invest in making partner at a law firm, now you always have the earning power as being a law partner.

Let’s say you both got law degrees. One person stops working and looks after the house and the other person focuses on their their career, gets all the benefits of that and then the relationship dissolves and the financial spoils are very unevenly split.

You’re not saying that no fault divorce is bad, because I mean obviously for women it’s made it a lot easier to get out of horrible abusive relationships. But there are downsides which make it more difficult to navigate for women in some cases.

Exactly. The question is, how do you change these laws so that you the best of both worlds. You absolutely need a way for a woman to get out of a really bad or abusive relationship and there’s economics research showing that for the women in the worst relationships, these changes to divorce law helped them.

But then there’s this broader piece of how being in a traditional gender role is really economically precarious, and that’s why I think it’s a non-starter to say we should go back to those traditional gender role. Because, like I said, we no longer have the legal framework that supported them.

So, speaking of divorce! I saw the discussion around your book without really knowing who you were or having read it. And that discussion was all framed as—you were someone who looked at the statistics on how much housework men did, and after crunching the numbers you decided to divorce and go become a lesbian.

And having read your book—I mean, like there’s a sliver of truth there, in that you’re bisexual and you decided to focus on dating women after you divorced. But that’s not really what your book is about!

And I wondered if you had thoughts on why that narrative seems so titillating to people in the press and on social media. Because it was a bit of a moral panic, right? It was like, oh, no, the feminists are telling women to become lesbians!

Yeah. There was one article about that which, like, I did agree to participate in. And I was like, yes, this is an interesting angle on one piece of the book.

But as soon as I did that article, then that was the only discourse about the book! And it was all of this pearl clutching. Maureen Dowd referenced it in her column! “We can’t have men and women just talking past each other and saying that they’re not going to be together!”

And of course that’s never what I was saying. In fact, I’m very supportive of heterosexual marriages that work. If you look at my research, it shows that marriage is actually really valuable as an economic institution. But what I’m saying is that it has to work for both parties involved.

And there’s particular types of marriages that I think are less advantageous to women, which are ones where if a woman is the primary breadwinner, and she does the lion’s share of the home production, then they do think that that particular type of marriage can be a bad deal. And so then you either renegotiate it or you get out of it.

But there are also a lot of marriages that work well for women. So yes, I do think I somehow hit a nerve culturally, because I think that this is everyone’s fear. Our fear is we know that things don’t add up if women decide that they’re going to opt out of this arrangement.

We’re not in the Handmaid’s Tail right now, we don’t have conscripted childbearing.

So when birth rates are falling, I think there’s this fear that women will say, we don’t want to do this anymore. And the reason that’s such a fear is because economically speaking, women are the producers of children.

After my divorce, I was planning on having a child on my own. And the only thing I needed to pay for then is sperm donation which is pretty cheap. It’s like $1,000 a pop, because it takes very little reproductive labor to create sperm.

But if I were a single man and I wanted to reproduce on my own, or in fact, a gay male couple, it’s very, very expensive, because you need eggs, and you need a gestational carrier. And both of those are an enormous amount of reproductive labor. So fundamentally, you need women to reproduce much more than you need men. And so it’s a very threatening proposition for women to say, “This might not be working for me.”

Which is why we now have these efforts to control women’s reproductive choices, right?

Yes, when you see birth rates falling, there is an effort to control women’s fertility, to say that’s how we’re going to stem this tide.

But I think a much more productive approach would be to say, how can we make this work better for women?

And by the way, I also want to add, some of that moral panic about my book was actually coming from women. Because I also feel like it’s very threatening for women if they are in a relationship where they might be getting a bad deal—it’s threatening to confront that there is an alternative. I think it can feel a little scary to confront that maybe there are some things that are kind of unfair.

But again, I’m not telling anybody to get divorced. I don’t think everybody needs to divorce their husband and marry a woman. I do think that everybody needs to marry someone who does the laundry. (laughs)

And I think there were times in my marriage that was kind of unfair that I said, if I start getting angry, I’m never going to stop. And I think there is something to that, that as women if you know that you’re getting a bad deal, if you start to let yourself document all those things, it can be a little overwhelming.

Getting out of a marriage is, often very stressful and financially damaging.

Women do often suffer financially after divorce, which is something I try to talk through a little bit dispassionately in the book. I’m just really trying to think about, are you better off in your marriage or out, if you’re really being honest?

And I think there are cases where women would be better off. And then there are also cases where there are things that are unfair and not working. But if you actually looked at the alternative, you wouldn’t actually be better off without this person here.

And you talk about how it’s not just about earnings, right? Because people like to spend time with their kids. If you’re in a marriage and somebody’s earning less, but gets to spend more time with the kids that’s not necessarily…

Yeah, that doesn’t necessarily mean that that’s a bad deal. And that’s, again, why I think it’s important to have an answer to lean in, because it should be about your utility function, right? If somebody says like, “Hey, I actually enjoy getting to spend more time with my kids, and so I’m kind of glad that, yeah, I’m carrying more of the home production burden.” That can be a fine deal, right? The thing that I push back on in the data is, when women are breadwinners, and they’re carrying the market production burden, they’re still carrying the home production burden too.

Most of your book is talking to women about how to navigate unequal systems. But you do have a concluding chapter where you talk about policies. I was interested in particular in your discussion of paid family leave policies, which is something people look to as a way to help women both at work and at home. But you argue that unless they’re carefully structured they can exacerbate inequalities. Could you explain that?

I want to be clear when I talk about this that if you say the objective in a paid family leave policy is to equalize across socioeconomic states, that can work.

Right now, wealthy women tend to have access to paid leave, either through their employers— because bigger employers in the US offer it because it’s not mandatory, it’s not federalized—or because their partners are wealthy enough that they can just not work for a period of time.

It’s poor women who tend to not be able to take that time off.

So you might say, I want to pass paid family leave this from the perspective of socioeconomic equality. And we know that, without a doubt, paid family leave is good for mothers, and it’s good for children.

Where I am being cautious is about the idea that paid family leave is going to close the gender wage gap. Because the data shows that in most cases, the paid maternity leave is going to widen the gender wage gap.

How does that happen ? First of all, there’s the case where a government just says, hey, you have to offer paid family leave, but they don’t pay for it. The firms are going to say, now if we hire women, we have this cost if we have to pay for the maternity leave. Whereas if we hire men, we don’t have that cost.

And the result is you see hiring discrimination.

And then there are countries where they’ve set it up right, where it’s a payroll tax, so everybody pays per employee, and then there’s a central pool of tax that pays for whoever’s on leave. So the firms are paying for it, but they’re not paying for it because they have a woman or because they have someone on leave. They’re just paying for it based on their employee headcount.

Even in this case you still get promotion discrimination. And this is evidence from Sweden from a paper by Mary Ann Bronson and Peter Toursie, where they show that firms are worried that if I give you a promotion and I put you in charge of a bigger team, the disruption is going to be bigger when you go on leave. So if I’m considering two people for a promotion, I’m going to, on the margin, give it to the man, because if I give it to the woman, I’m going to bear a bigger disruption cost when she goes on leave than when I just leave her in her entry-level position where she’s not in charge of anybody.

So they show that there’s this large gender gap in promotions that accumulates before anybody even has a child. And they can show that it’s discrimination by looking at childless women, because childless women, women who do not go on to have children, experience a lower promotion rate than their male colleagues until they hit age 40, at which point the firm’s like, oh, phew, she’s not going to have kids. And then she’s promoted at the normal rate again.

What this means is that paid leave can lead to increased hiring discrimination and it can lead to promotion discrimination. And also we see larger so-called child penalties [negative impact on women’s careers relative to men] in countries where they have more paid leave, because women spending more time outside the labor force creates a differential in career growth between men and women.

Again, from a perspective of closing socioeconomic inequality, federal paid leave is really good. From a social justice and economic justice standpoint, nobody should have to go back to work out of economic necessity while they’re still breastfeeding eight times a day an infant whose stomach is the size of a marble, and while they’re still bleeding, and they’re still physically recovering from childbirth.

But from a gender wage gap perspective, you have to be careful. And so some of the best designs are the one that you want to have it first, paid for centrally, so that’s payroll tax.

Two, at the firm level, because of this disruption cost when somebody is on leave, you actually want to figure out a way to make your managers whole when they have an employee out on leave, so that they’re not experiencing that as a cost. So we have an extra bonus pool that this team gets when they have somebody who’s out on leave, or you get a 1.5 Full-Time Equivalent replacement in your budget.

You talk about some other things that help to give women more choices and equalize opportunity. That includes things like better reproductive care, better in vitro options. And the opportunity for queer women to date other women, right? Because you say that household divisions in lesbian households are much better in terms of...

Yeah, they’re more egalitarian. It depends more on who earns more money rather than just being that the woman does more.

And it struck me reading all those suggestions that these are all things that the fascist regime is trying to roll back. There are a lot of attacks on the ability of queer people to exist in public spaces. There are attacks on reproductive care. From your perspective, how much is that going to limit women’s options? Where are we headed?

Well, I think the thing that I worry about—I mean, I worry about so many things, Noah. But I think the thing that I worry about is that typically we see these policy changes, they impact the most the women with the least options.

My advisor had a paper on abortion access in Romania that was in Freakonomics. And what he showed is that wealthy women were able to circumnavigate abortion bans. They still got abortions. It was poor women who weren’t able to.

Anytime you have these policy changes, they most affect the people who have the least options to avoid them. I have a lot of options in my life, and therefore I’m going to be able to navigate and get through these challenges, but there’s a lot of people who won’t.

And even more broadly than just the attacks specifically on women’s rights, it’s also the attacks on public goods in general. Because the less the government does, the more time parents, and especially mothers, need to invest in making everything safe for ourselves and our children. If I don’t have a vaccine schedule that I can trust from the government, now I’ve got to do a whole lot of research myself and do a whole lot of calling around to find what I’m supposed to do to keep my child safe.

And again, it’s going to be wealthier parents who are able to do that and still able to access that care, and it’s going to be poorer parents who aren’t going to be able to. The less that we can trust that our food supply is safe, the less we can trust that our air and water is clean, the less we invest in those public goods, the more things like that have to be privately provided.

And that is incident on parents, but it’s really incident upon mothers.

Okay—that was my last question! Unless you had something else you feel we didn’t cover?

That’s a depressing note to end on!

But I think I will end on saying that, the reason the policy changes are in the last chapter of the book is that I didn’t want the book to say, if those other things don’t change, then you’re just fucked.

Because that’s just a very depressing place to live. I wanted to give women agency to say, yes, there are these external constraints. I’m not going to gaslight you about how much they suck. But you can still navigate those constraints and find your constraint optimum. And I’m going to give you some tools to still feel like you have more agency within those constraints.

And I think a key to that agency is kind of decoupling our vision of success from Sheryl Sandberg’s vision of success. Because, you know, we are navigating different challenges than she’s facing, and we might have different objectives than she has. So that’s why, given all those constraints out there, the best we can do is kind of find our own having-it-almost. And I hope my book helps people do that.

Great interview. I think the best way to frame arguments in an arguably out of control capitalist society is to base it on the financial cost of bad policies. What a great job this piece did of making it clear current policies ultimately will have negative impact on the economy. It's bleak that we can't just say this is bad for 50% and improvments can be made of our society but that is the current reality.

Hi Noah- a couple of things. First, wow, I love this interview. You ask great questions and the answers are detailed and hopeful despite the bleak reality. Second, and I know this sounds naive, but where’s the love? I’ve been married for 32 years to a man I love. If I thought about it just in economic terms, I might not be. But because of love, we’ve made a balance that works. I totally get and agree that people shouldn’t stay in marriages that they’re unhappy and overworked in. Talking can work if other things are good in relationships. It’s not all economic. Third, as a middle school teacher, I’d love to see a version of this for teen readers of all genders so they have their eyes open.