James Merrill And The Queer Carpet

On owning and erasing desire.

Well, the sale didn’t do quite, quite as well as I hoped, so I thought maybe I’d extend it a day or two? Admittedly it looks a little desperate, but you know, that’s only because I’m somewhat desperate. Best to own it.

40% off sale on annual subs, $30/year. If you like the poetry posts, you can encourage me by contributing!

—-

Last week I wrote about the wonderful Harlem Renaissance poet Claude McKay, and how recognizing his investment in queerness adds texture and depth to his poetry. Critics, though, often ignore or step around queer themes in poetry, even where you’d think they should be obvious.

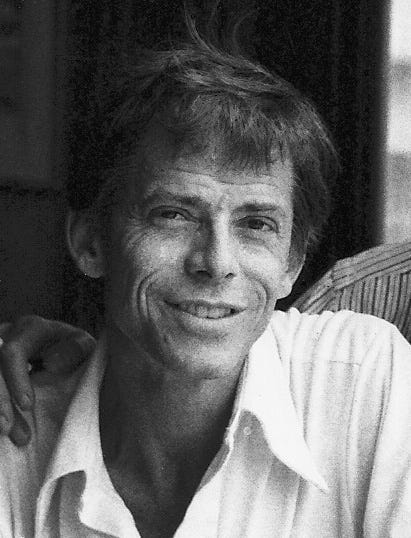

One somewhat surprising example is criticism of James Merrill (1926-1995). I say “surprising” because Merrill’s homosexuality is (certainly compared to McKay’s) very well known. He was the child of the founder of Merrill Lynch, and his wealth and privilege—as well as the advancement of the gay rights’ movement— allowed him to live his life more or less out of the closet, at least in comparison to McKay or (one of Merrill’s major influences) Auden.

And yet, critics can still be reticent about using queerness as a lens to read Merrill’s poetry. As one example, consider the reception and discussion of Merrill’s 1964 poem “A Carpet Not Bought”, which first appeared in The New York Review of Books.

A Carpet Not Bought

World at his feet,

Labor of generations—

No wonder the veins race.

In old Kazanjian’s

Own words, “Love that carpet.

Forget the price.”Leaving the dealer’s,

It was as if he had

Escaped quicksand. He

Climbed his front steps, head

High, full of dollars.

He poured the wife a brandy—And that night not a blessed

Wink slept. The back yard

Lay senseless, bleak,

Profoundly scarred

By the moon’s acid.

One after another clockStruck midnight; one. Up through

His bare footsoles

Quicksilver shoots overcoming

The trellis of pulse

—Struck two, struck three—

Held him there, dreaming.Kingdom reborn

In colors seen

By the hashish-eater—

Ice-pink, alizarin,

Pearl; maze shorn

Of depth; geometerTo whom all desires

Down to the last silken

Wisp o’ the will

Are known: what the falcon

Sees when he soars,

What wasp and orioleThink when they build—

And all this could

Be bargained for! Lord,

Wasn’t it time you stood

On grander ground than cold

Moon-splintered board?Thus the admired

Artifact, like clock

Or snake, struck till its poison

Was gone. Day broke,

The fever with it. Merde!

Who wanted things? He’d won.Flushed on the bed’s

White, lay a figure whose

Richness he sensed

Dimly. It reached him as

A cave of crimson threads

Spun by her mother againstThat morning in their life

When sons with shears

Should set the pattern free

To ripple air’s long floors

And bear him safe

Over a small waved sea.

Critics say, don’t buy that carpet!

The poem is an account of what seems to be a trivial consumer dilemma—should the protagonist, an unnamed man, purchase the (fabulous) carpet or not? The price is high, and he resists, but is tormented by doubt and insomnia, and spends all night tossing and turning and thinking of wonderful weaves. Finally, in the morning, the torment of desire leaves him, and he rests beside his wife. The poem ends as he thinks about how he is part of a generational pattern, in which people weave other people and those people weave still more, creating a safe, predictable, and satisfying life.

The most prominent critics who have written about this poem mostly take the vision of heterosexual bliss at face value. Stephen Yenser in The Consuming Myth: The Work of James Merrill (1987), says that the protagonist spends “a feverish night wrestling with the angel of matrialism” before “his better self wins out”—his wife embodying “that better self.” Yenser concludes that “love is the force that generates the significant design”—love here meaning conjugal, heterosexual love which creates children.

Similarly, Evans Lansing Smith, writing some 20 years and two decades of greater queer visibility later, still seems oblivious to queer readings of the poem in his James Merrill, Postmodern Magus: Myth and Poetics (2008.) Smith points out that the final stanza’s syntax is conflicted and confused in part because it uses numerous pronouns without antecedents (“her,” “their,” “him.”) But rather than discuss the possible gendered implications, Smith simply suggests that mother and wife are fused into a mythic archetype who is preparing the protagonist for the journey into life and death. Again, the carpet is figured as a distraction from the main heterosexual business of living and love.

For both Yenser and Smith, Merrill becomes a conventional sexual moralist—or worse, a moralist of conventional sexuality, celebrating marriage and procreation as a safe, spiritually satisfying alternative to unruly, crass desire.

This is, to put it mildly, a very odd reading of Merrill, whose exquisitely woven poems are consistently, even relentlessly, ironic, urbane, and knowing, and whose erotics are not (biographically or poetically) focused on heterosexual procreation.

James Merrill, anti-carpet?

So, what if we read the poem from that perspective? What if Merrill believes that the protagonist here made the wrong choice, and should have bought the damn carpet? What if the selfish, consumerist, shallow purchase of the carpet is a (deliberately surface-level) analogy to homosexual desire, which is often stigmatized as selfish, consumerist, and fallow?

“A Carpet Not Bought,” can be read as a story, not about refusing a carpet, but about refusing one’s own homosexual identity and desires. When the old man Kazanjian says, “Love that carpet./Forget the price,” the protagonists “veins race”—a phrase that evokes not just desire, but arousal.

The heightened affect, the sleepless night, is not about buying a carpet, but about the temptation of a passion which outstrips and overwhelms the relationship with “the wife,” who the man barely seems to notice. His life with her, his own backyard, is “senseless, bleak,/Profoundly scarred/By the moon’s acid”—an image of sterility and death.

In contrast, the carpet evokes a landscape of wondrous color. Orientalism has often linked the East to non-normative sexual pleasure, and Merrill evokes that to some degree. He also uses imagery of penetration (“Up through/His bare footsoles/Quicksilver shoots overcoming/The trellis of pulse”).

But perhaps most tellingly, Merrill suggests that the fascination of the carpet is the fascination of visibility; the carpet is all surface, and so shows all it is, and all it wants. The carpet is a maze shorn/of depth” and a

…geometer

To whom all desires

Down to the last silken

Wisp o’ the will

Are known…

Flipping “Wisp o’ the will” suggests the inversion of desire and of will, a sideways acknowledgment that the passions the man is feeling are queer. And the carpet is desirable because it shows, or mirrors, those passions and desires. When the man thinks, “All this could/Be bargained for!” the excitement is not just in the ease of purchase, but in the ease of embracing or accepting what he wants. These desires can be owned, they can be acted upon. He can see them. He can take up that carpet—and not just the carpet.

The exclamation, “Merde!/Who wanted things? He’d won.” is read by Yenser and Smith as a final triumphant rejection of mere stuff. But in a queer reading, the “Merde!” seems like an overdetermined reference to the anus, while “things” (especially in a stanza where we’re also talking about “snakes”) are unavoidably phallic. The answer then to “Who wanted things?” is that the man does—and winning here is a decidedly ambivalent, and almost certainly temporary, victory over his own desires and his own identity.

In the last stanzas, the man turns to his wife. But it’s notable that he does not turn to her with desire. Instead, she appears to him not as a flesh and blood person who he loves, but as a kind of abstracted symbol of heterosexual legacy and normality—“A cave of crimson threads/Spun by her mother…” which will lead him not to passion or feverish longing but will instead “bear him safe/Over a small waved sea.”

That sea could be death…but it also seems like it is again the carpet, which is (again) homosexual desire. By thinking of his wife, and her mother, and their children, the man is carried safely past his own insight into his own self, and what that self wants.

Not morals, but possibilities

Merrill isn’t condemning the man for choosing heterosexuality, any more than he’s condemning the man for being tempted by the carpet. Merrill was (again) influenced by Auden, but unlike his predecessor, moralism wasn’t really what he was about.

Instead, the poem presents possibilities, both of which are tempting, and both of which are to some degree ironized. The man here is choosing between two patterns for his life. One is filled with color and desire and thrilling, pulsing veins, but at the “cost” of safety and of being woven into heterosexual normality, with its comforts of family. The other requires the renunciation of “grander ground than cold/Moon-splintered board….” But it still has a “Richness,” and a worth.

The protagonist of the poem chose a heterosexual life. Merrill did not. And yet, his critics, by aligning him with the poem’s puritan protagonist, essentially try to shove Merrill back in the closet. Merrill’s tone is perhaps wistful, as he thinks about what he’s had to miss out on in a society that had not yet created a space for gay marriage. But he’s not just wistful; there’s more than a hint of mockery in the treatment of this abstemious consumer sweating and bucking beneath the covers, thinking of “things” while his wife sleeps beside him.

The carpet is there, in the poem’s finely woven lines, beautiful and beckoning. You can refuse to see the pattern. But that just means Merrill has caught you.

Yes! As if James Merrill would ever tell anyone not to get the carpet.

This is subtle logic, but it strikes me as sound.

You do a good job pulling out ambivalence in things. When we work with Counseling clients, that is often key.

“I hate that guy!“

Oh? What is the least objectionable thing about him?

“well, he does make good waffles…”

I could not have written this subtle a review, but I admire the capacity to do so.

Thanks.