Make Movies Horny Again?

The argument ignores some ugly history.

A brief notice before you start:

This piece was commissioned and then killed. This happens in freelancing. But with fewer and fewer outlets, especially for progressive writers, it’s harder to place rejected pieces, and harder to make up the lost income.

That means I’m relying more and more on the newsletter—and on you. I’ve got a 40% off sale today, $30/year. If you value this piece, and my work in general, please consider taking advantage of the offer and becoming a contributor.

—

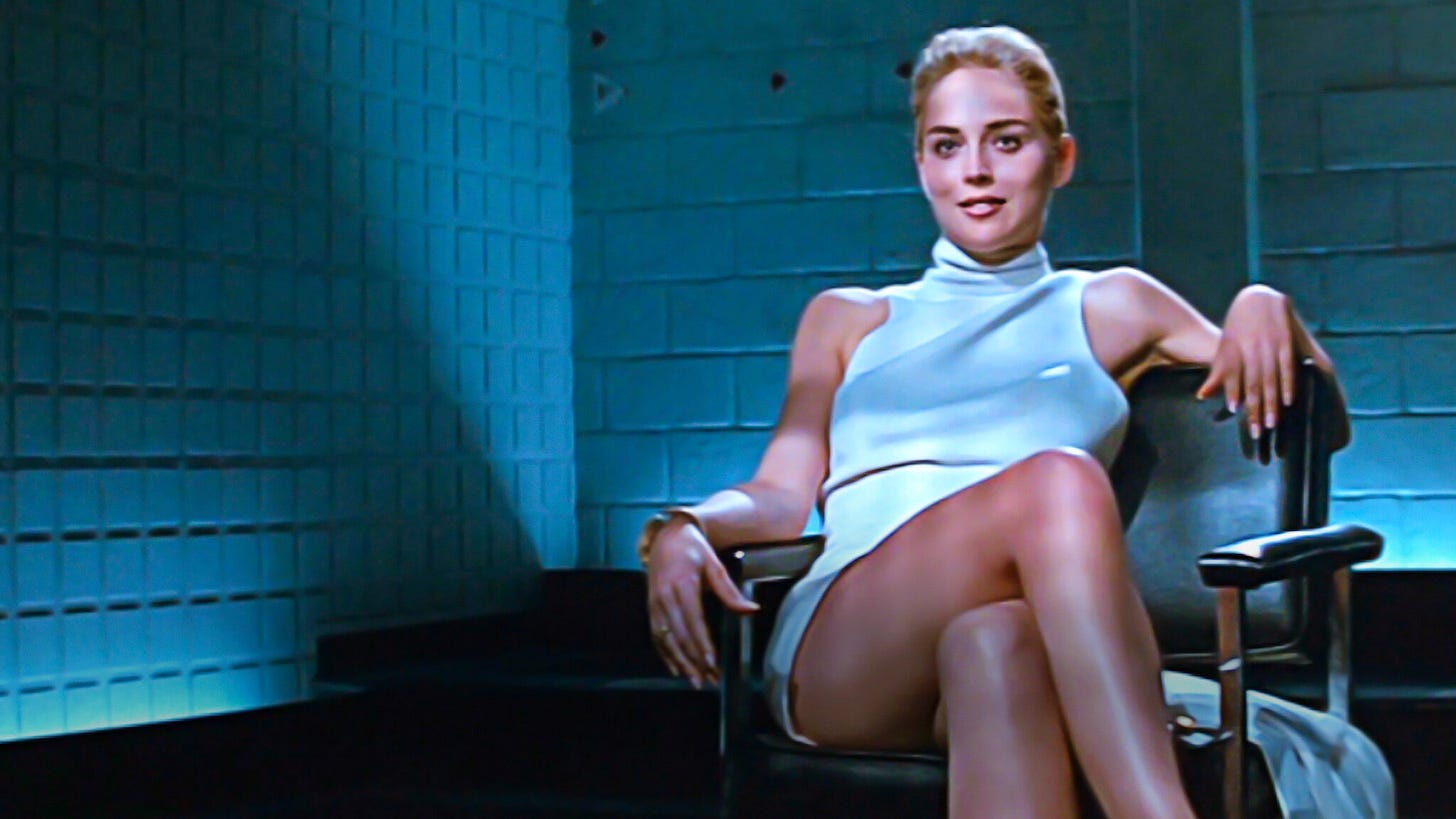

Movies today are not sufficiently horny, according to many critics and creators. Once upon a time, iconic sexy film moments looked like the (in)famous Sharon Stone crotch shot in Basic Instinct (1992); all cool provocation, sweaty lust, and explicitness. Nowadays, in contrast, “sexy” film moments look more like Gal Gadot in Wonder Woman (2017) stripping to her skimpy costume to charge across a World War I battlefield—perfect bodies transmuting potential erotic energy into violent spectacle.

These criticisms aren’t exactly wrong; superhero films are unusually uninterested in sex, and their box office dominance has de-hornified the theater experience to some extent. More, there’s some evidence that younger people want less sex on film—perhaps because they’d rather watch sexy content at home on streaming, but perhaps also because of the current right wing assault on sexual expression.

At the same time, though, the contemporary sexlessness of cinema can be exaggerated—and the virtues of past horniness can be much overstated. In particular, the critical praise for a sexier past erases the very stark historical limits on representation of queer sexuality, and the ways in which filmic lust, misogyny, and even outright abuse have often been intertwined in ugly ways. Puritanism in the current cinema has disturbing downsides. But we should be careful that nostalgia doesn’t blind us to past harms—not least because those harms are not, in fact, past.

Before talking about the problems with yesterday’s cinema, though, I think it’s important to acknowledge the problems with today’s. Raquel S. Benedict states the ethos of the modern superhero film succinctly in her already classic 2021 essay “Everyone Is Beautiful and No One Is Horny.”

“Actors are more physically perfect than ever…” Benedict writes, “And yet, no one is horny. Even when they have sex, no one is horny.” Benedict contrasts the awkward but enthusiastic John Connor conception scene in Terminator with the quippily chaste romance of Tony Stark and Pepper Potts in the Iron Man films. In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, she argues, bodies are fetishized as commodities for display, rather than seen as a “vehicle through which we experience joy and pleasure during our brief time in the land of the living.”

One thing Benedict doesn’t discuss directly is the way that bracketing erotics, or treating eroticism as unspeakable, can be leveraged to harm marginalized people. For example, the Christofascist right has been obsessed with banning LGBT books like Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer on the grounds that they are “pornographic.”

Kobabe’s book does discuss masturbation and it does depict horniness; it’s a coming-of-age story about a nonbinary person discovering their identity and sexuality. Conflating horniness and queerness with inappropriate or damaging content essentially makes any discussion of queer identity suspect and dangerous. When desire is written out of the human experience (as it is in many blockbuster films these days), it becomes easy to stigmatize people whose desires are seen as marginal or unusual.

It's important to note, though, that horny cinema past was not necessarily welcoming to LGBT people either. The much-touted horny Basic Instinct was a film about evil, murderous lesbians, one of whom is (more or less) redeemed through her relationship with a man. Similarly, Steven Soderbergh—a vocal critic of unsexy superhero films (“Nobody’s fucking!”)—also directed the wildly homophobic and misogynist Side Effects (2013). In that movie, an evil bisexual woman seduces her female therapist and the two proceed to torment the film’s One Good Man.

In contrast, right now there is an unprecedented renaissance of queer cinema which portrays and celebrates queer desire and queer horniness with a level of nuance and respect that would have been impossible even 15 years ago. Ethan Coen and Tricia Cook’s lesbian B-movies Drive-Away Dolls and Honey Don’t both gleefully and largely without judgment depict profligately horny women having sex with and desiring a range of other women. Close to You (2023) lovingly presents Elliot Page as a trans sex symbol with a complicated but ultimately requited sex life. The Oscar winning Moonlight (2016) is a painful, lyrical portrait of a Black gay man coming of age as he navigates trauma, violence, stigma and desire.

And I could go on and on: Titane (2021), I Saw the TV Glow (2024), Happiest Season (2020), The Power of the Dog (2021). You could certainly criticize many of these films for the way they present queer people or queer desire, and some are more sexually explicit than others. Some went directly to streaming (as film has become less horny, television has become much more so.) But none of that changes the fact that, despite our current Christofascist turn, and despite the dominance of non-erotic blockbusters, there are more and more positive depictions of queer sexuality and desire onscreen now than probably ever before in history.

Past depictions of eroticism weren’t just overwhelmingly heteronormative. They were also often misogynist, and worse than misogynist. In Goldfinger (1964) James Bond’s seduction of Pussy Galore looks in retrospect much less like seduction and much more like a rape. Celebrated critic Roger Ebert called it a “sexy karate match,” but what that meant in practice is that Bond physically overpowers Pussy Galore; the erasure of her ability to choose is treated as exciting or flirtatious. The fact that she retroactively enjoys the violation and abandons lesbianism is treated as an excuse or justification, but of course it isn’t. Instead, it's an example of how pop culture normalizes and justifies sexual violence.

There are no shortage of examples of Hollywood’s shaky understanding of consent. The worst involve actual instances of abuse—as in that Basic Instinct scene often cited as a masterpiece of horny cinema. According to Stone, director Paul Verhoeven did not get Stone’s consent to film her so explicitly; on the contrary, he lied to her and told her that her vagina would not be visible. She first saw the scene, “with a room full of agents and lawyers, most of whom had nothing to do with the project."

Stone said she agonized over whether to sue but ultimately decided against it for the sake of the film and her career. But deciding not to sue over harassment doesn’t mean the harassment stops being harassment. There’s a strong argument that the scene as filmed is itself a violation, and that what you are seeing on screen when you watch it is an act of abuse. (Verhoeven insists Stone knew about the scene.)

This is not an isolated incident. Maria Schneider says that a violent sex scene in Last Tango in Paris was filmed without her consent—which, again, means that the scene is essentially a record of her being sexually assaulted. Salma Hayek says that producer and notorious sexual abuser Harvey Weinstein forced her to include an explicit lesbian sex scene in her film Frida (2002). (Weinstein says he doesn’t recall pressuring Hayek.) Emilia Clarke said she felt pressured into nude scenes on Game of Thrones as a 23-year-old actress in 2011.

Obviously, there are many actors (of every gender) who are comfortable with sex scenes or with nudity, and many directors who respect their performers and work to make them comfortable. The use of intimacy coordinators since around 2018 has been helpful in this regard, and is a sign that the industry wants to improve.

But to acknowledge that the industry is working to improve, and should work to improve, you first need to acknowledge that the era of greater horniness had real downsides, and that a lot of the horny movies that people remember with fondness were built at least to some extent on homophobia, misogyny, and violence

Sex, sexuality, and horniness are all parts of human experience; they’re all things that creators and viewers need space to portray, to think about, and to enjoy. One of the things we need to think about, though, is how Hollywood has often in the past failed to treat these issues, and its own workers, with respect, dignity, and care. I think there’s a good argument for more horniness in films in the superhero era. We need to be sure, though, that when we call for greater horniness, we aren’t glamourizing past abuse.

The question should be: is this content relevant to the plot of the movie, or is it just being used as exploitative time-filler? There is a difference...

"you first need to acknowledge that the era of greater horniness had real downsides, and that a lot of the horny movies that people remember with fondness were built at least to some extent on homophobia, misogyny, and violence"

So, like the anti-porn "feminists", you want MORE censorship in the name of Queer Representation? Because THAT is what it sounds like you're asking for!

Yes, portrayals of LGBTQ characters were originally highly offense and very male-gaze oriented—the repeated horror or "comedy" of seeing a sexy lady who turns out to be a transvestite or crossdresser offended me even before I accepted I was, if not trans, trans-adjacent. (I hesitate to call myself "trans" not because I'm scared or offended by the label, but because I'm not sure I qualify as I mostly live and present as a male.) But it seems that awkward period of embracing homo/transphobia as the first step towards admitting LGBTQ persons even exist (remember how for decades Hollywood's Production Code meant you couldn't even talk about gay people?) is the way that we get through to acceptance and embracing LGBTQ persons as people, too. What the Trump Right, with the connivance of Fine Mainstream Liberals, is trying to do isn't trans demonization as much as trans erasure.

I don't know if I've said this already, but the French comedy LA CAGE AUX FOLLES, which was hardly an enlightened view of LGBTQ people, probably did more for gay and trans rights than a thousand ACT UP marchs did—because it got the Nice Republican Moms in Middle America to come out of the theater saying, "You know, those gay people and guys dressing up in women's clothing are loving spouses and parents, too, just like us!" You could say the same for VICTOR/VICTORIA, which made LCaF look like a gay rights treatise(!), because those Moms who wouldn't see a "French Art Movie" came out the theater saying, "Well, I think Robert Preston and Alex Karras make an adorable couple, and why shouldn't they?"

I don't know if every culture has to go through "Sexual Villainy" and Misogyny on its way to Accepting and Embracing "Horniness", and certainly it should be pointed out when it happens—but it sounds more like you want to throw out the baby with the bathwater, Noah.