Professor X Isn't MLK. He's Booker T.

On the problems with mutant respectability politics

Yesterday I posted a long essay on W.E.B. Du Bois lifelong struggle with elite vanguard politics. As a follow up, I thought I’d reprint this piece on one of Du Bois’ intellectual rivals, Booker T. Washington, which ran at the Escapist way back when. And also it’s about the X-Men, because why not?

—

The X-Men have often been seen as an analogy for racist injustice. In the X-Men universe, mutants are hated and feared, just as black people have been hated and feared in real life. Fans often like to compare the X-Men's peaceful leader, Professor Xavier to Martin Luther King, Jr., and the militant antihero Magneto to Malcolm X.

The truth, though, is that Xavier isn't much like MLK. He's philosophically much closer to an earlier, more contentious civil rights leader: Booker T. Washington. Washington was a conservative figure more than 100 years ago. The fact that the X-Men still reproduce his politics is a sign of just how reactionary the franchise often is, and how shallow its thoughts on racism and prejudice can be.

Booker T. Washington embodied respectability politics—the idea that, as Damon Young writes at the Root, "if we walk a little straighter and write a little neater and speak a little clearer, then white people will treat us better." Washington was freed from slavery after the Civil War and went on to advocate for technical and vocational education for black people; he founded Tuskegee Institute in 1881. He pointed to his considerable triumphs as evidence that black people could succeed if they worked hard and adopted an attitude of "adjustment and submission," as W.E.B. Du Bois termed it in a famous critical essay.

One of the most famous passages in Washington's autobiography, Up From Slavery, describes his efforts to gain admittance to Hampton University. A white administrator demanded he clean a room, and he did so with gusto and thoroughness. He boasted, "When she was unable to find one bit of dirt on the floor, or a particle of dust on any of the furniture, she quietly remarked, 'I guess you will do to enter this institution.'"

Cleaning skills don't have much to do with preparedness for educational training; the woman was determining whether Washington was sufficiently obedient and deferential. Washington believed that fulfilling her expectations would allow him, and other black people, to advance.

The problem with respectability politics is that they don't work. They also end up reinforcing the racist ideas they are supposed to fight.

Racism is irrational; it's not a logical reaction to the behavior or work ethic or appearance of black people. Barack Obama was a Constitutional scholar who took care to never appear angry or ruffled. But that didn't stop racist conspiracy theorists from claiming he was a secret foreign radical Muslim terrorist working to destroy America. The existence of the remorselessly polite, amazingly accomplished Booker T. Washington didn't cause white people to abandon Jim Crow, either. On the contrary, segregation and racism grew more entrenched during Washington's lifetime.

Respectability politics "shifts responsibility away from perpetrators (which in this context would be America) and places it on the victims (which in this context would be blacks in America)," Damon Young explains. It blames racism on the immorality and failure of black people, rather than placing the blame where it belongs—on the immorality and hatefulness of racists.

Respectability politics have been dismantled by everyone from W.E.B. Du Bois to Ida B. Wells to Ta-Nehisi Coates . But they still remain popular—as the history of the X-Men demonstrates.

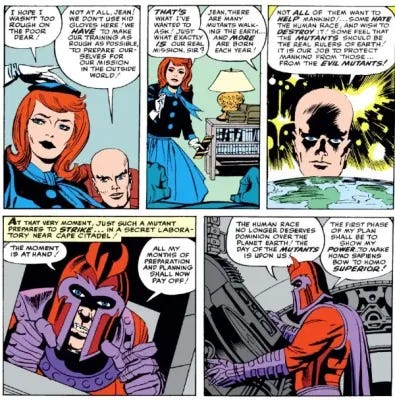

The very first X-Men comic from 1963 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby is an exercise in Booker T. Washington style propaganda. The story introduces Professor Charles Xavier, who is, like Washington, an educator with his own school. And like Washington, what Xavier teaches is respectability. He gathers young mutants—people who were born with altered genes that give them superpowers. And he teaches those mutants to hide their differences and conform to "normal" human standards.

One extended sequence in the comic shows the mutant Angel strapping his wings into a painful harness so he can pass as a non-mutant in polite company. As for the plot, it involves Xavier sending his mutant team out into the field to protect military bases from sabotage by Magneto. "It is our job to protect mankind from those…from the evil mutants!" Xavier declares. Here he goes further than even Booker T. Washington, who never pushed respectability so far as to suggest that black people should ingratiate themselves with the US government by forming a paramilitary unit and going out to beat up other black people.

Obviously, the X-Men have come a long way since 1963; many different people have written stories about them, and the characters have been tweaked and changed in innumerable ways. But the respectability politics core has persisted through the vast majority of versions.

Some creators have had Xavier using the X-Men as a cover; they're masquerading as superheroes fighting evil threats in order to find and pursue their true goal of finding and protecting other mutants. But hiding behind a veil of respectability politics is still respectability politics. Xavier still believes that you fight discrimination by pretending to be decent upstanding citizens, like Washington, rather than by directly challenging racist policies, like King or Malcolm X.

The Fox X-Men film series generally follows the respectability politics script too. Throughout the series, Xavier's X-Men fight other mutants in order to show that mutants are trustworthy and good and respectable, and so should not be discriminated against.

X-Men: Apocalypse in 2016, for example, features a mutant whose power allows him to increase the abilities and strength of other mutants. This resulting revolutionary movement is framed as world-threatening and evil. So, inevitably, Xavier (James McAvoy) organizes his team to fight against literal mutant empowerment in the name of protecting the status quo.

In 2019’s Dark Phoenix, it's revealed that Xavier's respectability politics worked; after beating up their fellow mutants in Apocalypse, the X-Men are treated as heroes. But in a very smart critique, Mystique (Jennifer Lawrence) warns Xavier that the material success he cherishes—the visits to the White House, the awards, the media attention—won't last.

She's right. After Xavier demands that Jean Grey (Sophie Turner) risk her life to demonstrate once more that mutants are good, she is injured and suffers a mental collapse. Jean starts using her powers to destroy things. As soon as she does, Xavier's muckety-muck political friends turn on him, and start pushing anti-mutant legislation.

Respectability politics require all mutants to act perfectly all the time, and to continually sacrifice themselves for humans. It's an impossible ask. No one is perfect all the time, and no one can be continually self-abnegating without building up a well of resentment and anger. Respectability politics can sometimes allow one person or another—like Xavier, or Booker T. Washington—to gain status and influence. But "everyone be perfect all the time" isn't a reasonable response to discriminatory policies or to hatred.

Dark Phoenix ends with the X-Men recognizing that Xavier's approach is unsustainable, and removing him from his position as head of his school. They even rename the institution for Jean Grey, the flawed, unrespectable mutant.

It's a thoughtful close to a movie series that wasn't always especially thoughtful. Hopefully, when the X-Men make their way into the Marvel Cinematic Universe, creators will take the hint and give Xavier a less bankrupt ideology. Booker T. Washington's accomplishments were impressive, and he's an admirable figure in many ways. But it's past time for the X-Men to move beyond him.

Great piece. This comparison always annoyed me bc it reflected how white liberals viewed MLK/Malcolm X. Malcolm was not a terrorist who promoted active violence against white people — just self defense (he arguably sounded more peaceful regarding race relations than the Israeli government does regarding Gaza). MLK didn’t have a Danger Room. He was overtly non-violent!

I love this. Well done. As someone who was raised to default to respectability politics due to the dangers of being a black man in America, this article really speaks to me.