Sartre as Antifascist, Sartre as Antisemite

The good and the not so great in Sartre's *Anti-Semite and Jew*

You can find an index of all my substack posts on fascism here.

Sartre's Anti-Semite and Jew continues to be cited in present-day discussions of fascism, and for good reason. Writing at the end of World War II, Sartre's insights about fascist bad faith reasoning and about their longing for an organic purified community of hate remain eloquent and convincing.

It's also true, though, that there are ways in which Sartre participates in the antisemitism he denounces. In doing so, he calls some of his claims about the character of the antisemite into question. By focusing on the antisemite, as a person, rather than on antisemitism as an ideology, Sartre frames bigotry as a kind of character flaw rather than as a social structure in which he participates.

The Antifascist Sartre

Again, Anti-Semite and Jew is much praised. Even so, it's worth reiterating its virtues. Sartre is especially brilliant in describing the way in which antisemitism and fascism are ideologies of fundamentally bad faith. Antisemites lie, not least to themselves, in insisting that their hatred of Jewish people is based on their experiences with Jews. Instead, as Sartre explains, experiences with Jewish people are interpreted by the antisemite through a lens of hatred.

Antisemites claim to be merely expressing opinions, Sartre says—and opinion is "the word a hostess uses to bring to an end a discussion that threatens to become acrimonious."

But Sartre says, antisemites are not engaged in coffee-table discussions; they are instead lobbying to remove certain people from their seats at the coffee-table, more or less permanently. "I refuse to characterize as opinion a doctrine that is aimed directly at particular persons and that seeks to suppress their rights or to exterminate them," Sartre says.

Instead, Sartre says antisemitism is a "passion," and he expands: "Anti‐Semitism is a free and total choice of oneself, a comprehensive attitude that one adopts not only toward Jews, but toward men in general, toward history and society; it is at one and the same time a passion and a conception of the world."

That conception of the world, in Sartre's view, might be called revanchist petit bourgeois rage. People of middling success, wealth, or attainment are antisemites, Sartre believes, the better to secure themselves the honor/power/nobility of privileged access to the heritage and laurels of French national identity. The antisemite identifies himself with this past, and therefore sees himself as immutable, and as capable, with that immutable community, of doing violence and spreading fear. "The phrase 'I hate the Jews,' Sartre says," is one that is uttered in chorus; in pronouncing it, one attaches himself to a tradition and to a community—the tradition and community of the mediocre."

Antisemites have rejected alike reason, honor, and justice; they see themselves as superior and above such concerns. That insight gives rise to the much-quoted, and quite magnificent passage in which Sartre explains why argument with antisemites is pointless.

Never believe that anti-Semites are completely unaware of the absurdity of their replies. They know that their remarks are frivolous, open to challenge. But they are amusing themselves, for it is their adversary who is obliged to use words responsibly, since he believes in words. The anti-Semites have the right to play. They even like to play with discourse for, by giving ridiculous reasons, they discredit the seriousness of their interlocutors. They delight in acting in bad faith, since they seek not to persuade by sound argument but to intimidate and disconcert. If you press them too closely, they will abruptly fall silent, loftily indicating by some phrase that the time for argument is past.

The Antisemitic Sartre

So far so good. The problems mostly start when Sartre moves from discussing the antisemite to discussing Jewish people (or "the Jew" as he prefers to put it.)

As Michael Walzer explains in an introduction, Sartre was not especially knowledgeable about Jewish history, Jewish scholarship, or Jewish contemporary life in France (or anywhere else). He writes with good will, but with little knowledge.

Inevitably, the results are erratic. Sartre's constantly admitting the truth of Jewish stereotypes and then walking them back (as when he writes that Jews killed Christ, then adds in a footnote that no, they didn't) or else explaining that those Jewish stereotypes are understandable and not the fault of the Jews.

The second is the more common approach. For instance, Sartre claims that Jews are obsessed with money not because of a flaw in the Jewish character, but because money is a "universal" and so appeals to the understandable Jewish desire to escape particularist invidious stereotypes—an argument that lightly leaps over the fact that Jews are not in fact especially obsessed with money, ffs. Sartre also goes on at length about how Jewish people have no history or common faith or intellectual tradition other than oppression—an argument which (a) is nonsense, and (b) dovetails perfectly with antisemitic smears about Jewish rootlessness

Similarly, much of the book is given over to a discussion of which Jews are and which Jews are not authentic. Sartre insists that Jewish inauthenticity is the fault of antisemites, not of Jews. But he is oblivious to the way that labeling any Jewish people as inauthentic feeds into the antisemitic stereotypes and hatred he claims he wants to confront.

I could go on; the passage where he claims some deep insight into Jewish self-alienation based on an anecdote about a Jewish man visiting a brothel and being unable to perform with a Jewish sex worker is a low point.

So is Sartre's claim that "there have been no Jewish surrealists in France." He goes on to muse that surrealism is beyond Jewish people because "surrealism, in its own way, raises the question of human destiny "while prejudice and discrimination have mired Jewish people in the social and particular." There are several problems with Sartre's argument here, but the most obvious one is that there were plenty of French Jewish surrealists, including Moïse Kisling, Claude Cahun, and Marc Chagall—the last of whom Sartre actually mentions elsewhere in his essay!

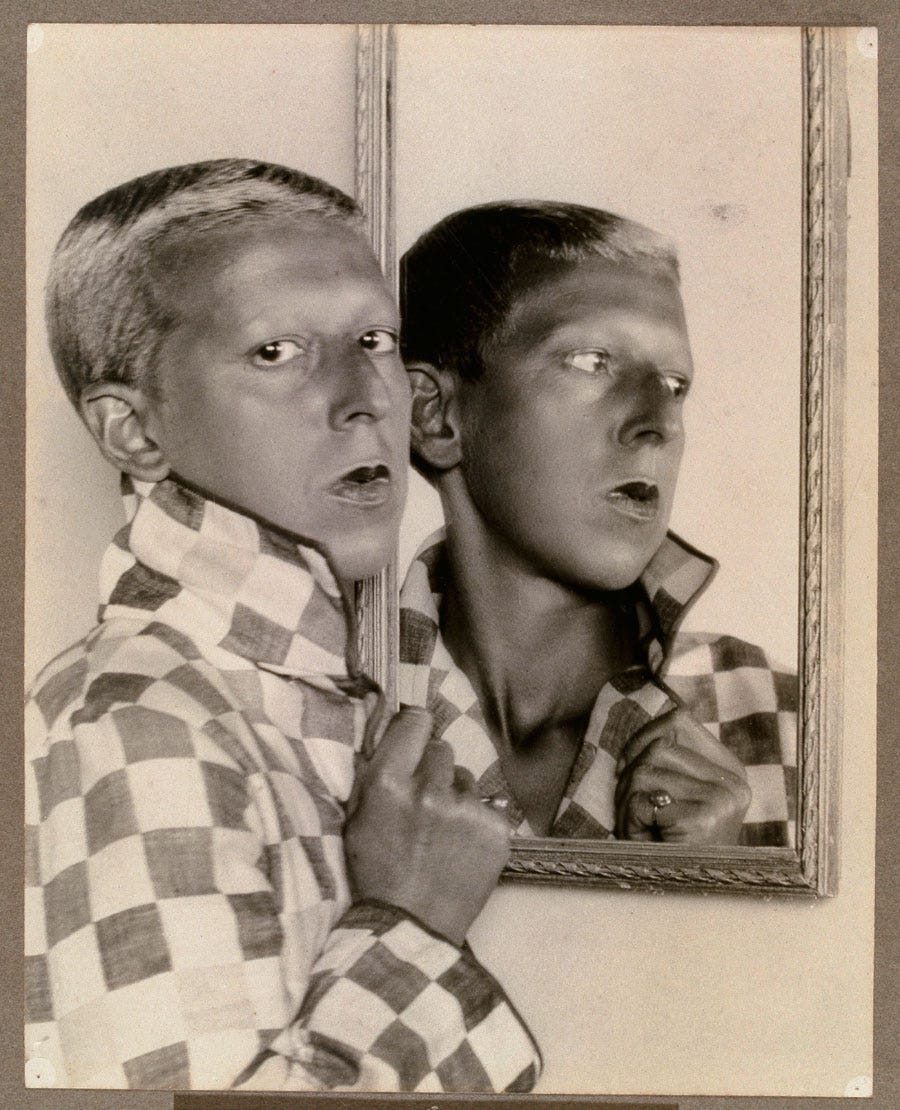

Image: Claude Cahun, Autoportrait (1929)

Antisemitism for All

In the pre-Google age, it's not that surprising that Sartre didn't instantly come up with the names Kisling and Cahun. But it's worth asking, if you're not an expert in surrealism, and you're not 100% sure that there are no Jewish French surrealists (and again, without google how could you be sure?) then why would you go on for a couple pages about why Jewish character is incompatible with surrealism? Wouldn't you maybe pause for a second to think, "Hey, I don't know that much about Jewish people. I don't know that much about surrealism. Maybe I should slow my roll lest I fart out utter bullshit?”

Sartre did not pause though. That's in part because he's an egotistical philosopher certain that his philosophizing, no matter how half-baked, is worthwhile. But I think it's also because, as a French gentile, he felt he had the right to define Jewish people, and Jewish thought, despite not knowing much about either.

That's a core way in which antisemitism works. Yes, as Sartre says, there are committed antisemites who are antisemitic by passion. But there are also people who simply assume that their position as "normal" or normative gives them a clear view of...well, everyone. Sartre doesn't feel like he needs to know much about Jewish people, because what is there to know? He is the studier; the marginalized are the object of study. Why should he not rule on the authenticity of Jewish people, or on their suitability as surrealists? He is a dispassionate, unmarked, outside observer. He's entitled.

This sense of gentile entitlement is widespread. Antisemitism is certainly the ideology of open, committed fascists who want to exterminate Jewish people. But it's also a broader, more generalized sentiment that Jewish people should take a back seat—even in the discussion of antisemitism, even in the definition and discussion of how antisemitism affects Jewish people.

Sartre is blind to his own participation in this second kind of antisemitism, and that colors and I think undermines some of his judgments about antisemites. In particular, he sees "the anti-Semite" as a particular character type—an individual who can be delimited and analyzed. Certain people are antisemites; others, like say leading left French philosophers, are not.

Again, Sartre characterizes antisemites as mediocre men—never pausing to explain how, then, Racine, or Heidegger, or for that matter, Shakespeare, could have been antisemites. And he argues, on the basis not even of anecdote, that antisemitism is not found in the working-class, and goes on to insist that "the socialist revolution is necessary to and sufficient for the suppression of the anti-Semite." Sartre is doubly distanced from antisemites as a leading intellectual and a leftist. Thus assured, he can tell fun anecdotes about Jewish impotence with great self-confidence.

Solidarity Means Listening to Jews, Not Just Studying Them

Sartre doesn't just propose socialist revolution as the solution to antisemitism. He also argues, thoughtfully and convincingly, for solidarity on the basis of shared interests. "We are all bound to the Jew, because anti‐Semitism leads straight to National Socialism," he says. "Not one Frenchman will be free so long as the Jews do not enjoy the fullness of their rights." Sartre proposes an organization to oppose antisemitism everywhere in France. Such an organization, he says, would not be a pallid liberal fight for supposedly universal values, but would instead be a "concrete community" built on passion and a recognition that the destiny of the French nation and the destiny of Jewish people are inseparable.

It's a stirring and moving vision. It's also worth noting though that Sartre sees this league as being gentile-led. He notes that a Jewish league for fighting antisemitism is being constituted. But he then quotes a Jewish acquaintance who is nervous about fighting antisemitism outright. On the strength of this one person's opinion, and without apparently speaking to anyone actually organizing the Jewish league, he proposes a separate, broader gentile league.

Sartre's reasons are noble—antisemitism, he correctly argues, is everyone's problem. But he nonetheless is once again putting himself at the center of fighting antisemitism. Why build new institutions rather than empowering and uplifting current Jewish ones? If you are standing with Jewish people, stand with them, not in front of them.

I want to be clear that it's very important for non-Jewish people to speak about and think about antisemitism. And I'm not saying Jewish people always know more about antisemitism than gentiles. Sartre's insights are really important and helpful. I've thought a lot about antisemitism, and I still learned things from reading Anti-Semite and Jew.

But part of fighting antisemitism as a gentile is recognizing that Jewish people are your peers and your interlocutors, not just your objects of study. If you find yourself speaking for Jews and about Jews much more than you listen to Jewish people, you may know the antisemite you're denouncing more intimately than is altogether comfortable.