“You Can Use Me”: The Aesthetics of Whiteness

Manet's Olympia, Ghost (1990), and Rizvana Bradley’s Antaesthetics

This was a time intensive essay which I can only write because of your support; no commercial site is paying for this! So, if you find it useful or valuable, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you!

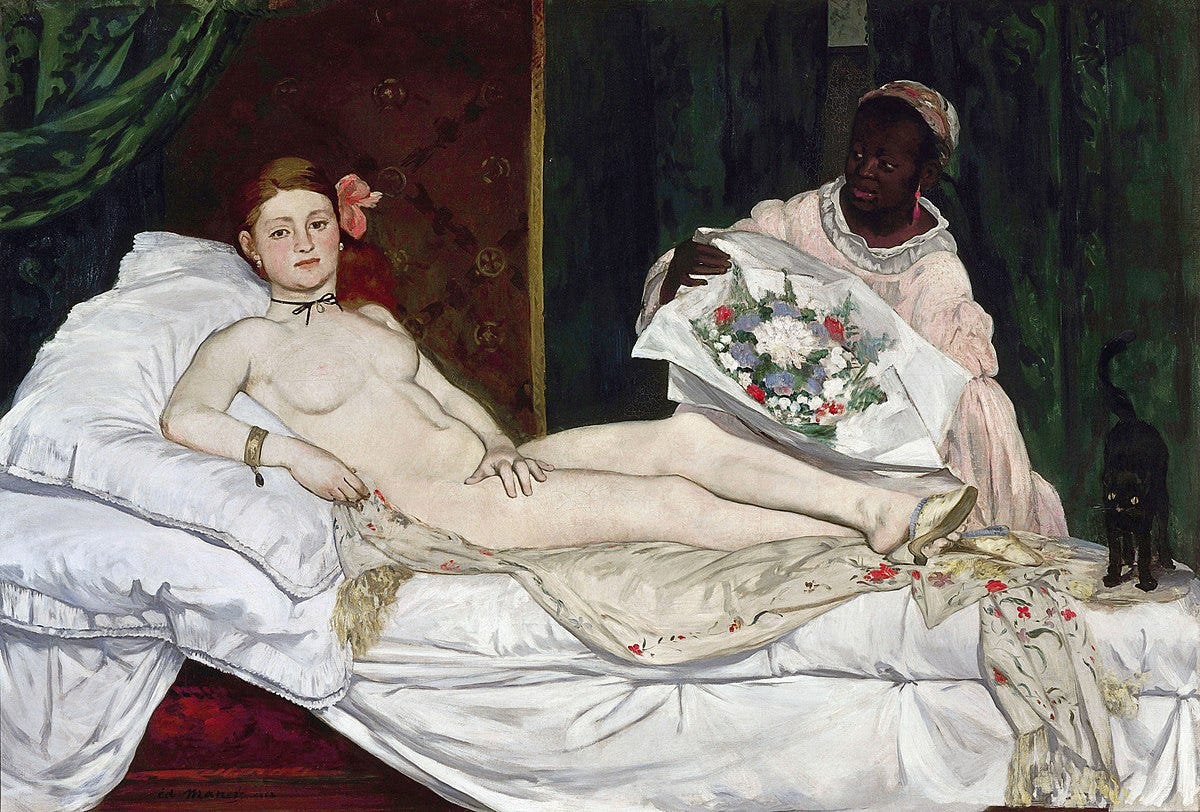

Manet’s 1863 Olympia is one of the defining paintings in the history of the white female nude. It’s also, as Black women scholars have pointed out, an important milestone in the representation of Black women in Western iconography. The representation of gendered difference in the painting is doubled by a representation of racial-and-gendered difference.

The juxtaposition isn’t an accident; rather, the Black woman in the picture makes possible, or structure, the aesthetic representation and consumption of (white) gender and (white) sexuality. Black female exclusion enables the representation and possession of gender—which is why the Black best friend is a ubiquitous trope in (white) romance, and why in the US currently the party of white supremacy is obsessed with targeting and tormenting trans people.

Aesthetics is Structured by Racism

This essay was largely inspired by the discussion of Olympia in Rizvana Bradley’s Antaesthetics: Black Aesthesis and the Critique of Form (2023). Bradley’s philosophical prose isn’t always easy to parse. But one of her central insights (to the best I can paraphrase) is that racism is implemented through and as aesthetics, and that in turn aesthetic form is structured by the exclusion of Black people, and especially of Black women.

Bradley cites Marxist critic and theorist Terry Eagleton, who says that “the modern notion of the aesthetic…is no more than a name for the political unconscious: it is simply the way social harmony registers itself on our senses, imprints itself on our sensibilities”. Bradley continues:

Unfortunately, when it comes to the most influential discourses of critical aesthetic theory, raciality has been largely occluded from substantive inquiry, presumed as epiphenomenal and marginal to the most pressing intellectual questions. A central contention of this book is that black existence has from the beginning been an (ante) aesthetic problematic, one which has necessitated the work of “rethinking ‘aesthetics,’” as Sylvia Wynter puts it.

For Bradley, aesthetics is the way that we see and think about social harmony and political organization; it’s a name given to what, in life and society, seems right and what seems wrong. Race, and Black existence, is often excluded from discussions of aesthetics and presented as a minor issue or a specialized and marginal concern. But that is itself a sign of the way that aesthetics depends on the violent erasure of Black experience and Black presence.

Black existence is “before” aesthetics, Bradley argues. That “before” indicates both that Black existence precedes the formation of an aesthetic regime, and that Black existence stands before the aesthetic regime which judges and violates it. Bradley concludes that her book “emerges from my conviction that now, as always, aesthetics are a matter of life and death.”

The Power of Nobody Looking

Bradley doesn’t provide a full reading of Olympia, but her discussion is a helpful place to start in understanding her argument and in thinking about what the Black woman in the picture is doing there—or, historically, in critical analysis, not doing there.

Notoriously, as Bradley notes, in his groundbreaking Marxist study, The Painting of Modern Life, T. J. Clarke argued that Olympia is a painting of class difference and class hierarchy—and that class difference and class hierarchy is specifically visualized by nakedness and exclusion. “The sign of class in Olympia was nakedness,” Clarke wrote. “Olympia’s class was nowhere but in her body: the cat, the Negress, the orchid, the choker, the shawl—they were all lures, they all meant nothing, or nothing in particular.”

In his revised edition, Clarke apologized for not fully engaging with the existence of the Black woman in the picture (though he does not apologize, notably, for the racist slur.) “I remember one of the first friends to read the chapter saying, more in disbelief than in anger, ‘For God’s sake! You’ve written about the white woman on the bed for fifty pages and more, and hardly mentioned the black woman alongside her!’”

Clarke admits that he has been bitten by “the snake of ideology” (an unfortunately phallic metaphor in an analysis of a nude) and then tries to rectify his lapse. “I would now add the fiction of ‘blackness’ meant preeminently, I think, as the sign of servitude outside the circuit of money—a ‘natural’ subjection, in other words, as opposed to Olympia’s ‘unnatural’ one.”

Bradley notes drily that it’s odd to argue that Black people are outside the circuit of money since they have historically been actually bought and sold. But she says Clarke “is right to suggest that the subjection of Olympia’s maid lies before history, whereas the subjection of Olympia can be elevated to the status of a properly historical conflict, one whose part in propelling the (antiblack) world can be at least avowed.” Or, to put it another way, Olympia is a thing to be possessed, while her maid is possessed as nothing.

The contrast here is not, Bradley emphasized, one of mere hierarchy or contrast. The Black woman is not (or at least not only) depicted as a kind of (supposedly) ugly contrast to highlight Olympia’s desirability. Rather, the Black servant frames Olympia’s desirability as aesthetic form. The Black woman isn’t just highlighting beauty, but making that beauty possible, assimilable, and consumable.

It’s useful here, I think, to look at what Olympia’s maid is actually doing. Olympia, famously, looks out directly at the viewer, who stands in as her client, with a gaze that could be sad or challenging or bored or all of those. The maid, however, looks not at the client/viewer, but at Olympia. Her facial features are dark against the dark back paneling, and are therefore difficult to make out. But she appears to be admiring or curious as she tries to hand Olympia the large bouquet from a (presumably male) admirer.

Within the picture, then, the maid is essentially a stand-in for, or a conduit of, the male gaze, and of male desire. When you (the male viewer) look at her, you are directed by her eyes to look over again at Olympia; you become the maid looking at the nude. The orchids, contra Clark, are not “nothing in particular,” but are instead a flowery sign of the world outside the frame—the visible indication of desire conveyed from an admirer (the client, the male viewer) into the world displayed for view.

The Black woman, then, is not object or subject of a circuit of gendered gaze and desire. Yet she is crucial as a conveyor of both. She resolves, or elides, a central problem of the nude which Manet’s scandalous picture highlights as a scandal—the problem of presence.

The historical nude presents a (white) woman as available to the viewer to be possessed. Yet, the woman is not actually there in the flesh—or, perhaps more accurately, the male viewer is not actually there in the picture. Painting gives the viewer the woman as object, but it also excludes the viewer, who is literally not in the painting. The male viewer is a ghost, watching; the aesthetic act of possession dematerializes the viewer, who can only own flesh via absence.

That’s why nudes like Ingres’ 1839 Odalisque With Slave are often set in the Orientalist harem; the women on display are available but guarded. The secret access is part of the aesthetic thrill, but also part of the aesthetic frustration; consummation is promised in the foreground and withheld by the Black eunuch in back, guarding the wares.

The Black maid (like the Black degendered guard) resolves this quandary of possession. Because she is nothing before the aesthetic, her position and her gaze can be taken by whoever wants to, or by whoever looks at her. She is not a rival, because she is nothing. She is not desirable, and/or desire enters her without resistance. She embodies a history of violent expropriation, and therefore is an assurance of the untrammeled operation of power and satiation.

Olympia’s hand famously obscures her genitals, denying access just as the viewer is unable to enter the room. But there is another opening—the Black woman, who holds that spread white bouquet. The men who look at Olympia may be ghosts, but they have more substance than the Black woman in the painting, who they can possess and appropriate. The aesthetic’s complicated promise and disavowal of satisfaction is anchored by the Black woman whose violent dispossession stands before the aesthetic as an assurance of white empowerment, white possession, and white gendered fulfillment.

Possessed by Race and Gender

As with the nude, so with the romance; they are both genres/forms which present themselves as mostly predicated on gendered relationships between white people. Yet, these relationships and forms are dependent on the violent exclusion of Black women.

There are innumerable examples of Black mammies or servants in Hollywood narratives, from Gone With the Wind on to Bridgerton, and arguably morphing into the Black best friend in romcoms and romances. The common ground in these stories is that Black women are adjuncts to white women’s stories; they provide support and advice, but do not have their own plots, romances, or interiority. Like Olympia’s maid, they are there to establish the reality of white aesthetics, white sexuality, and white romance through their very nonentity.

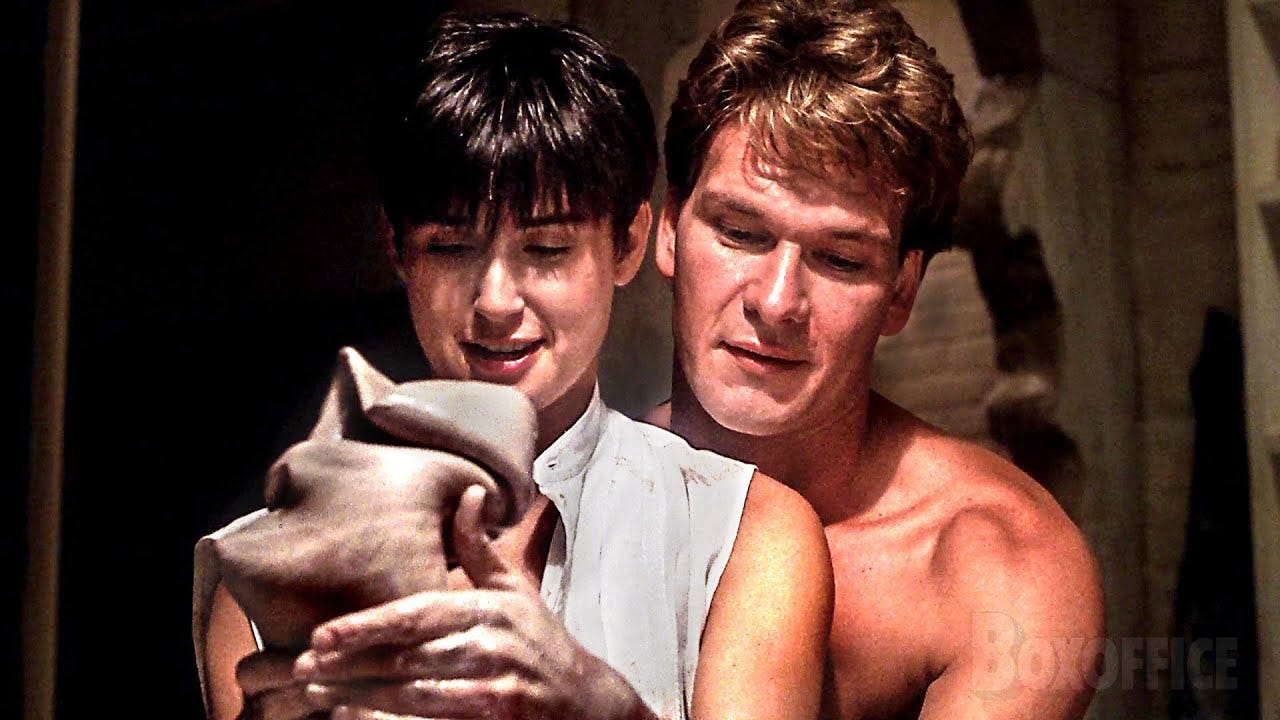

One of the most telling examples of this dynamic is Jerry Zucker’s 1990 megahit Ghost. The film is about the romance of banker Sam Wheat (Patrick Swayze) and his girlfriend, interior designer Molly Jensen (Demi Moore.) The two seem to have a perfect “charmed” existence, until they are mugged coming out of a performance of “Macbeth.”

Sam is killed—but he doesn’t quite stay dead. He lingers as a ghost, who can see and hear Molly even though she cannot see or hear him. While investigating his own death, he discovers that he was set up by his best friend, Carl (Tony Brunner). Carl was embezzling and didn’t want Sam to catch him; he also has designs on Molly.

Ghost, even more perhaps than Olympia, is obsessed by the contradiction of aesthetic empowerment and disempowerment. As Laura Mulvey argues in her famous essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” the male hero (in this case, Sam) is the main point of identification for the audience in standard Hollywood film. The male hero drives the plot and provides a sense of heroic progression; he fights male villains and canoodles with the female lead.

But the dynamics of male engendering are interrupted by Sam’s death. He is transformed from active hero to ineffectual viewer, unable to affect the plot—much like the actual audience in the theater, staring at the screen. Like the pitiful protagonist in DePalma’s Body Double, Sam “like the viewer, spends his time gazing. But the gaze is the opposite of empowering. [He] can't actually touch the object of his desire; he's a pitiful voyeur.”

Sam’s problems of disembodiment and consequent disengenderment start to resolve when he stumbles on spiritualist Oda Mae Brown (Whoopi Goldberg). Brown is a con artist, or so she thinks. But it turns out that, pushed by Sam, she really does have the ability to hear ghosts. Sam bullies her into relaying messages to Molly, and even into reappropriating Carl’s embezzled cash. Eventually, in the movie’s climax, Sam possesses Oda Mae’s body so he can touch and kiss Molly one last time.

Per mammy and Black best friend tropes, Oda Mae has no romantic relationships of her own. She has sisters who help her with her spiritualist scam. But they’re little more than comic relief and we know virtually nothing about them, even though Sam’s interventions put their lives at risk too. Goldberg is by far the most charismatic actor in the film, yet she has no real life of her own outside of ventriloquizing Sam. Like Olympia’s maid, Ola Mae is off to the side, looking at Molly for Sam, and conveying to her his desire. It’s notable that Sam, who like many a reticent stoic Hollywood hero has trouble expressing his emotions, never tells Molly directly how he feels about her. The first time he says, “I love you” to Molly, he’s already dead. It’s Oda Mae who has to repeat the phrase and relay the message.

Sam, like the viewer, can’t actually affect the action onscreen. When he tries to punch Carl, his hands go right through him. Similarly, Sam, like the viewer, can’t express his desire for Molly—both because he can’t speak the words and because she can’t hear him. The aesthetic dream of proper gendered empowerment and embodiment is undermined by the fact that it is a dream. Consummation is seductive, but just out of reach; the famous pottery scene, in which Molly and Sam have sex after sinking their hands into clay, is a promise of tactile aesthetic sensuality which the vision on screen can’t actually deliver. Sam does not possess the pot, or the girl. He possesses nothing.

Which, again, is where Oda Mae comes in. When Molly and Sam say they wish they could touch one last time, Oda Mae is (as it were) touched. She offers herself to Sam: “You can use me. Use my body.” The words both evoke and deny a history of white male sexual violence against Black women, and the subsequent scene continues in that obscurantist vein. Zucker films one chaste shot of Oda Mae and Molly’s hands touching. But the rest of the scene shows Sam touching and embracing Molly, even though it’s putatively Oda Mae’s body.

The movie is carefully forswearing lesbian connotations (hinted at, perhaps, in Molly’s short hair and boyish clothing.) But Zucker is also, literally, erasing Oda Mae’s presence. Sam displaces her; the violent exploitation of Black women is mentioned and then reiterated as a magic empowerment of the (male, white) viewer, who fulfills romance arc and gendered destiny alike by possessing and then discarding Black femininity. Sam can fully inhabit the aesthetic, and fully possess Molly, only because he is standing in the place of Oda Mae. It’s significant too that the song that plays during the love scene is The Righteous Brothers’ “Unchained Melody”—the most famous exemplar of blue-eyed soul, a genre in which white people sing in a musical style created by and appropriated from Black people.

At the end of the film, Sam ascends into white light and Carl is pulled down into hell by black shadows. Oda Mae wanders off after assuring Sam that she bears no ill will for having her life risked and her body expropriated. Her job is done; she has facilitated the romantic and heroic arc of a white couple.

Though “job” is perhaps not the right word, since Sam insistently refused to let her keep the $4 million that Carl embezzled. Oda Mae, if paid, would have her own narrative and her own agency. Just as Olympia’s maid’s flowers are not for her, so Oda Mae cannot have anything of her own. She secures Sam’s purchase on the world by having nothing, and being nothing, except the conduit of his words and his will.

Who Owns the Giant Phallic Sandworm?

Olympia was painted more than 150 years ago. Ghost was released in my lifetime, but that’s only because I’m old. Black women may have been treated as a nothing to be possessed in paintings and movies past. But surely things are better now?

Well, maybe. The aesthetic of Olympia and Ghost is still pretty common, though. In Dune: Part 2, Paul (Timothée Chalamet) becomes emperor of the galaxy largely through the help of his Fremen lover Chani (Zendaya) a Black woman who teaches him the ways of the desert. However, to officially ascend to the throne he needs to set Chani aside and marry the princess Irulan (Florence Pugh). Empowerment involves using a Black woman to gain possession of a white woman.

Similarly, The Holdovers, is about the relationship between boarding school teacher Paul (Paul Giamatti) and student Angus (Dominic Sessa). The school’s Black food service director Mary Lamb (Da’Vine Joy Randolph) encourages Paul to be less rigid and dictatorial, facilitating his connection with Angus. Patriarchal mentorship and succession, like heterosexual connection and desire, is enabled by a Black woman who is the perfect conduit because she is not a presence herself. Paul’s kindness to her demonstrates his virtue, even as her placement before the aesthetic cosigns the rightness of reconciliation within white patriarchy.

Both Dune 2 and The Holdovers are arguably more aware of the racism in building power and plot on Black women’s exclusion. Chani is angry at Paul’s betrayal, and the viewer is supposed to feel for her, even though Paul—who has precognition—assures us that she will eventually come around and accept her place in Dune 3.

The Holdovers is careful to tell us something of Mary’s life (her son died in Vietnam) and to give us a few glimpses of her relationship with her family. But these mainly underscore that her story is in many ways more interesting and more dramatic than the narrative we’re being directed to follow. Why isn’t The Holdovers her story? The answer seems to be that Mary, like Olympia’s maid, is more important for who she is looking at than for who she is in herself. The fact that she cares about Paul and Angus’ agonistic plot arc vindicates that plot arc. Her pain—the violent racist death of her son in the war— is taken from her to make the story of white men who didn’t have to go to war more meaningfully aesthetic.

Black women are often represented in racist ways, through stereotype, hypersexualization, desexualization, and denigration. Beyond that, or before it, though, Bradley argues, Black women’s exclusion from the aesthetic makes the aesthetic possible by reaffirming the empowerment of white patriarchy. That’s why Ron DeSantis’ Florida has been simultaneously banning courses about Black history and gender affirming care for trans people. Racial hierarchy undergirds gendered division and gendered hierarchy. Black women must be nothing if white men (and white women too) are to experience the pleasurable aesthetics of gaze, romance, narrative, succession—all those white flowers to possess.

Almost over my head, but fascinating. Thank you.

It’s far from the nuts and bolts stuff I usually read, but I thought you did a good job of keeping it accessible. You avoided the psycho-babel that makes a lot of the critical examination of art incomprehensible to average folk.