Fiction Cultivates Empathy, Not Morality

They aren't the same thing.

In Dangerous Fictions, Lyta Gold’s delightful study of moral panics about reading and fantasy, she takes a wrecking ball to the tired notion that reading makes you a better person.

In 2021, a British judge passed an unusual sentence. When presented with the case of a young neo-Nazi who had been caught with thousands of pages of white supremacist manifestos and how-to guides for making bombs, the judge ruled that the neo-Nazi should—instead of receiving jail time—simply read the classics of British literature, such as Shakespeare, Austen, Dickens, Hardy, and Trollope. The neo-Nazi did a little bit of the reading, and then—if you can believe it—he turned around and became a Nazi again. Austen and Shakespeare didn’t de-Nazify him; they didn’t turn him into a compassionate or anti-racist person. The only real question here is why the judge believed they might.

This judge, whether he knew it or not, was caught up in what critic Jennifer Wilson has called “the Empathy Industrial Complex,” a process by which fictional stories are extolled and valued for their supposed ability to produce empathy. Gottschall enthuses that stories are “an empathy generator” and function as “empathy machines,” cribbing from Roger Ebert’s famous description of cinema as “a machine that generates empathy.” The pop psychology writer Johann Hari has referred to novels as “a kind of empathy gym,” as if literature is something to be suffered through in the gym of the mind, turning those pains into gains.

Gold goes on to point out that many well-read people are not especially empathetic. She also notes that the empathy industrial complex seems to be aimed mostly at encouraging the moral elevation of white liberals; the trauma of minority writers is exploited as a kind of ethical resource to improve the majority, just as mineral wealth in the colonies was exploited to benefit the metropole. “The empathy-industrial complex is ineffective,” Gold concludes, “or at least is effective at building something other than empathy.”

I don’t disagree with the conclusion—though I might quibble with the terminology. For Gold, the problem with the empathy-industrial complex is that it doesn’t produce real empathy. But maybe the problem is that empathy, like the novel, is not actually a tool of moral elevation in itself. The issue isn’t that fiction doesn’t create empathy. Rather the issue is that fiction creates empathy, but that empathy is not (necessarily) a virtue.

Feeling with other people, putting yourself in the shoes of other people, doesn’t have to make you better. The mistake is not in linking fiction to empathy; the mistake is in linking empathy to morality.

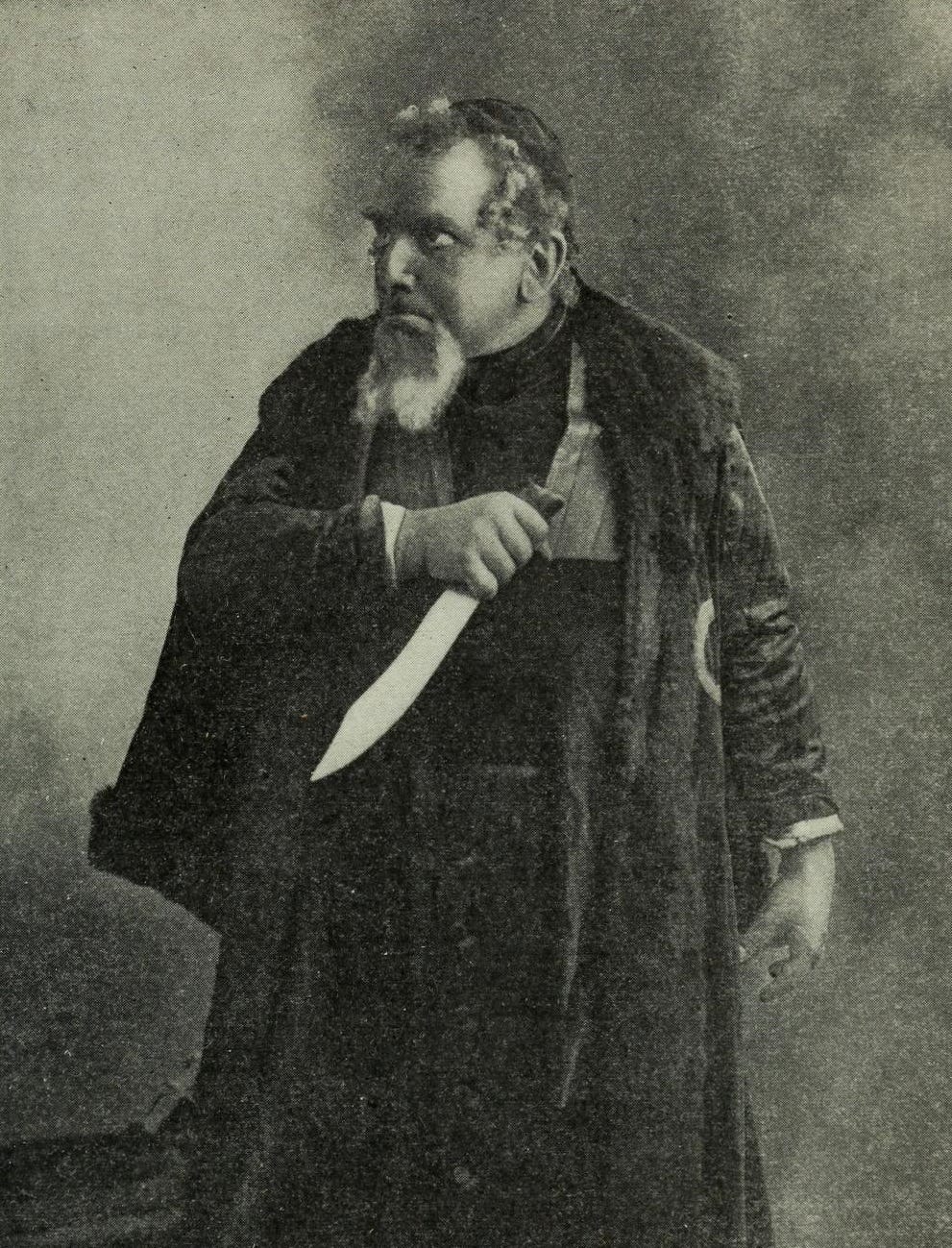

Shylock and Empathy

I’ve discussed some of these issues before in different contexts—particularly in regards to action movies. Action movies are set up to get you invested in the virtue and trauma of some appealing protagonist so that you then see it as reasonable/fun/virtuous when that protagonist murders tons of people. You empathize with James Bond or John Wick and cheer them on; you are on their side, which means you root for them to electrocute their opponents or plunge daggers in their eyes. Empathy isn’t a spur to greater understanding here; it’s a way to make violence justifiable/fun (within the context of the film.)

Of course, John Wick is not Tolstoy or Jane Austen. People who are invested in the empathy industrial complex will often argue that, sure, pulp crap is pulp crap; it’s only highbrow, deathless literature which really leads to a universal, uniform understanding of the value of all perspectives. Downing junk food is bad for you; eating your spinach, though, will turn your weak ethics into Popeye the strong moral man.

Shakespeare, with his wonderful talent for “negative capability”, is the iconic example here—and the iconic example of that iconic example is probably Shylock’s speech in The Merchant of Venice. Shylock’s insistence on his own humanity—“Hath not a Jew eyes?”—is supposed to instruct the reader to see marginalized people as fellow sufferers, with equal moral standing and, ideally, equal rights.

There are some problems with this reading though. First of all, and most obviously, Shylock’s speech, within the play, convinces no one. The people on stage, who Shylock addresses directly, within the fiction, are impervious to his arguments. They (including his own daughter!) continue to see him as a devious damned villain, who deserves to be stripped of his property, humiliated, and forcibly converted. The play is filled with rabidly antisemitic sentiments…as when Shylock explains why he hates Antonio:

I hate him for he is a Christian;

But more for that in low simplicity

He lends out money gratis and brings down

The rate of usuance here with us in Venice.

In other words, Shylock is motivated by anti Christian animus and by greed. Antonio doesn’t jack up his rates of interest sufficiently.

In this context, is Shylock’s speech really supposed to put you on his side? Consider the reading by Dara Horn’s young son, after he heard the play for the first time.

Shylock’s just saying he wants revenge! Like, ‘Oh, yeah? If I’m a regular human, then I get to be eee-vil like a regular human!’ This is the evil monologue thing that every supervillain does! ‘I’ve had a rough life, and if you were me you would do the same thing, so that’s why I’m going to KILL BATMAN, mu-hahaha!’ He’s just manipulating the other guy even more!

And sure enough, if you read the whole monologue, Shylock is stressing his humanity not as a plea for mercy, but as a justification for his own hatred and villainy.

To bait fish withal. If it will feed nothing else, it will feed my revenge. He hath disgraced me, and hindered me half a million; laughed at my losses, mocked at my gains, scorned my nation, thwarted my bargains, cooled my friends, heated mine enemies, and what’s his reason? I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.

Shylock is not trying to convince you that everyone is human and deserves respect. He’s trying to convince you that his revenge is justified. And Shakespeare is trying to convince you that Jewish people are sophists who will hurt good Christians if they can.

Empathy as fun

You could argue here I suppose that Shakespeare is not modeling real empathy—but again, this speech is one of the most cited, most revered examples of Western literature’s capacity to stoke (real) empathy. If Shylock’s speech is not real empathy—with its direct, impassioned, eloquent call for you to step into someone else’s skin—then real empathy doesn’t exist.

I think real empathy does exist. I’d just argue that it doesn’t have to be connected to moral uplift. Shakespeare is putting you in Shylock’s shoes; he is asking you to feel with Shylock. He just isn’t doing that in order to get you to treat Jewish people (or anyone) better.

So why is he doing it? Well, I think there are a couple reasons. First, as even most Hollywood screenwriters are aware, completely unsympathetic villains make for boring stories. A villain who is just evil and hateable, through and through, and who has no relatable motive at all, drags down the whole narrative and makes it seem wooden.

Killmonger in Black Panther is the go to modern superhero example; his critique of racism is convincing and powerful, even as the film makes sure to show you his gratuitous evil and violence so you don’t get too, too invested. The movie isn’t encouraging you to switch sides to Killmonger, exactly. But it knows that the film’s themes and conflicts resonate more powerfully, and are more engaging, if the villain has some solid arguments. As Dara Horn’s son suggests, you’re not supposed to fall for the villain monologue, but the villain monologue is fun because villains with passion and good arguments are even more dangerous, and therefore more difficult (and more satisfying) for the protagonist to overcome.

Empathy as warning

Along those lines is the second reason for empathy in this context: villains are more scary, and more hateable, when you can empathize with them. Shakespeare encourages you to understand Shylock and to see things from Shylock’s perspective so that you understand how much Shylock hates you/the good guys/the Christians.

When you stand in Shylock’s shoes, what you see is Shylock’s resentment, hatred, and jealousy. Yes, that hatred and resentment is arguably justified in some ways. But that only makes it more implacable and more impossible to negotiate with. Shylock hates Christians for good reason; that means that Christians cannot propitiate him or parley with him. Empathy is used not to encourage mutual understanding, but to teach Christians that there is no bargaining with Jews.

Champions of the connection between empathy and morality believe that if you understand that person over there, you will treat them more kindly. But what is often touted as the greatest evocation of empathy in all of history suggests that this is overly optimistic. Empathy might make you kinder in some situations. But it also might steel you in your cruelty. If you understand why they hate you, you might cease hating them, sure. But you also might conclude that their hatred is unbridgeable, and that you’d better get them before they get you.

Narratives teach empathy, not morality

I’m not arguing that empathy is always evil. Nor am I arguing that watching Merchant of Venice or Black Panther is inevitably morally corrupting. What I’m saying instead is that:

a. works of literature rely on and cultivate empathy, and

b. cultivating empathy does not inevitably make you a better person and isn’t even intended to make you a better person.

Empathy is, or can be, entertaining. Fiction and narrative rely on empathy to encourage reader buy in, to create complex investment, to build up heroes and build up villains, to let you experience love, rage, fear, courage, hope, spite. People like fiction because it makes them feel things, and without empathy, most stories would feel like nothing.

But feeling things that others feel doesn’t guarantee that you will take their side. It might make you want to position yourself as their heroic savior, which is more satisfying in general than being a victim. Or, as Shylock shows, feeling for someone else might even turn you against them.

The Empathy Industrial Complex in its focus on empathy as a cure for all moral ills, is essentially a marketing endeavor, much like the wellness complex whose rhetoric it often purloins. Gold does a good job of questioning the easy conflation of literature and uplift. I think she could extend her skepticism, though, to empathy itself, which like the narratives which supposedly inculcate it, is not really meant as an ethical nostrum. It certainly can’t substitute for actual moral commitment or for actual solidarity.

As an ELA teacher, I have seen “cultivating empathy” as a reason to make sure our students can access literature. My question is: does practicing empathy through literature translate the skill to everyday life?

If it can do that, then I’ll get behind the argument. There’s plenty of compelling reasons to teach kids to read already, but if the skills learned while using empathy to enjoy literature translate to real life, it would be worth some focus. Not because it’s moral, but because it’s a valuable skill to have while living in a society.

Thank you for bringing this up.

Hm…

Feeling a little lost by what empathy means in this discussion. Maybe sympathy is a better fit.

In child development, studies find that children learn empathy by observing it being given, and by receiving it themselves.

One of the biggest variables then in children’s developing a capacity for empathy for others, is their parents modeling of giving it, both to others and to the child.

Irrespective of empathy, from reading this essay and discussion, I would say Shylock, like Trump simply does what bullies do: tells the story from the middle while entirely avoiding his own initial transgression.

That is how bullies are able to speak with such self-righteous, persuasive confidence and authority when claiming victimhood. Even to themselves, they start the story in the middle.

Thanks for a stimulating read all around.