Has Social Media Led America Into Fascism?

Charles Sumner’s caning suggests that the answer is “no.”

Most right-thinking people agree that we are stuck in an unending fascist nightmare of misery and cruelty and horror. There can, though, be good faith disagreement about how we got here exactly, and about how we get out.

One of the big ongoing disputes is about whether we have been blundering in the fascist tarpit for aeons, or whether it’s a more modern, gleaming new tarpit which has snuck up upon us with its gleaming new tarpit thrusters. Internet gadfly (and my friendly acquaintance) Will Stancil is one of the more tenacious proponents of the tarpit thrusters theory—or of the “social media is destroying us all” theory, since it’s probably time to abandon my silly tarpit metaphor.

—

This is a post that I am sure I could not place as a freelancer. I am excited to get to write it for you…but! I can only keep writing things like this if people support me. Now is a good time to do that! I have a sale today; 40% off, $30/year. If you like this piece, please consider coming on board!

__

Stancil acknowledges that motivated reasoning has always been a powerful force and that people have always convinced themselves of foolish and evil things. But, he insists, “Truth wasn’t endlessly malleable before. Something CHANGED and made it that way.” He adds, “It’s true that our sense of what is real and true has always been socially constructed…but what’s new is that we can now afford to have hundreds of different bespoke realities tailored to our biases.” Or, as he sums up:

I increasingly feel certain that the thing that has driven politics insane is the growing ability of people to find ways to validate their beliefs, no matter how incorrect and irrational. It started in right-wing media but has become central to all political discussion.

This is an argument that the internet, social media, and contemporary communication bubbles drive MAGA and Trumpism, rather than MAGA and Trumpism being longstanding threads in US politics which have been picked up by new media but not necessarily transformed by it.

For Stancil, fascism, and fascist conspiracy theories, may have existed in the past, but it was at least somewhat marginalized by, and at least somewhat manageable because, “truth wasn’t endlessly malleable before.” There was a stronger collective sense of shared reality; you could not just toss a conspiracy theory into the internet and have it endlessly replicate like a Covid virus, killing us all.

I (mostly) disagree with this; I think we tend to underestimate the power and the appeal of fascist conspiracy theories in the past, in part because our history textbooks and collective memories tend to treat unhinged rabid assholes with power as if they are statesmen and thoughtful actors (sound familiar?)

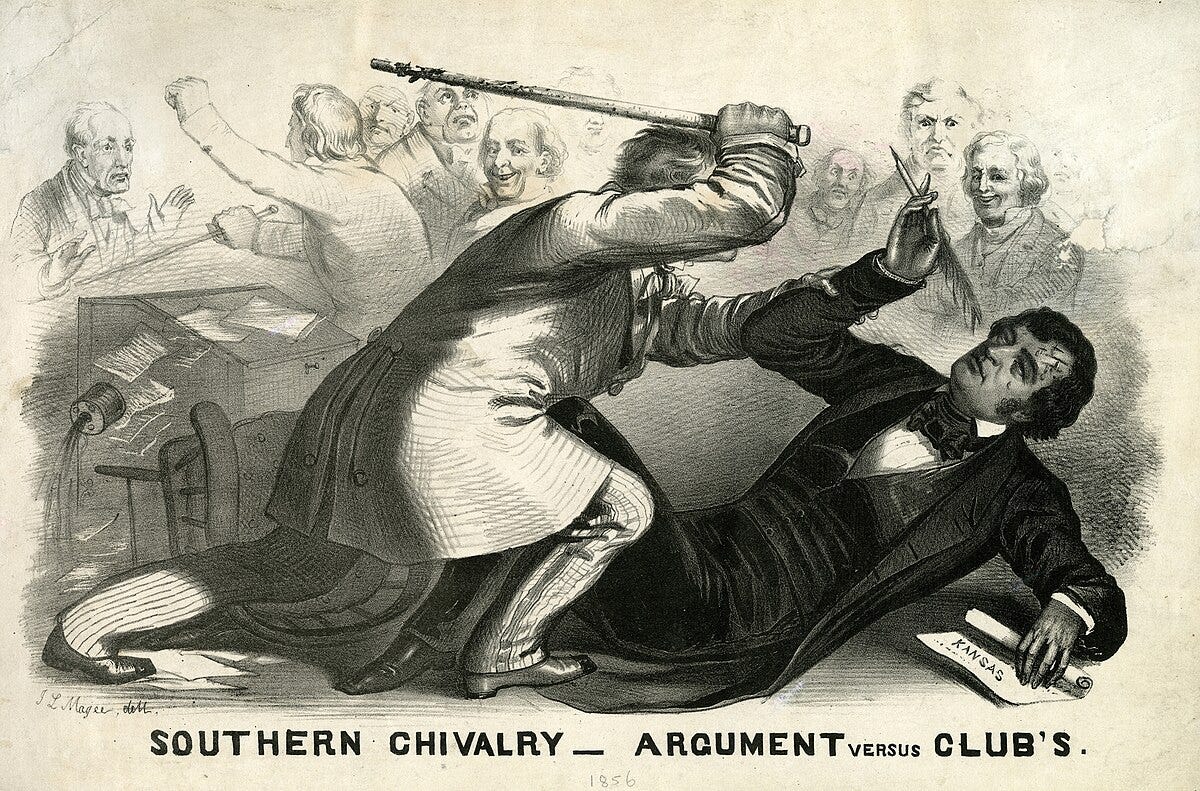

As an example, I think it’s worth considering the caning of Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, and specifically how the caning was perceived and explained in the South.

You Are Faking and Also It Is Good You Were Harmed

As I discussed in a post earlier this week, I’ve been reading Stephen Puleo’s excellent biography of Sumner, a remarkable antiracist who personally did as much as any politician to advance the cause of abolition and equality in the years before, during, and after the Civil War.

In 1856, Sumner delivered an impassioned anti-slavery speech in which he lambasted South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler in personal terms. Butler’s relative, representative Preston Brooks, was incensed, and felt it was his duty (and his pleasure) to physically assault Sumner.

He did so on the floor of the Senate, beating Sumner so viciously and unmercifully that he split his head open to the skull. When Brooks’ cane snapped, he went on beating Sumner with the fragmnts. Other people on the floor attempted to go to Sumner’s aid, but Brooks’ pro slavery colleagues prevented anyone from reaching him, threatening them with bludgeons and guns. Sumner collapsed, insensible—but even then Brooks kept on hitting him. “I repeated it till I was satisfied,” he said of the beating in his later, self-satisfied account.

Sumner was so badly hurt he was in serious danger of death or permanent brain injury after the caning. He experienced debilitating headaches and weakness in his legs which made it impossible to stand. His back injuries interfered with his sleep; he could not work, think, or rest, for months, and longer than months. He also appears to have suffered from something like PTSD; even after he was more or less healed physically, he found sitting in the Senate chamber, where he had been attacked, almost impossible. It was three years before he could return to work.

The North reacted to the caning with outrage; the beating helped rally antislavery sentiment, in part because it enabled abolitionists to highlight Southern barbarity and cruelty without focusing on or specifically discussing slavery.

In the South, however, Brooks became a hero. After the House tried and failed to censure him, he resigned but was returned in the next election as a hero. People from all over the South sent him commemorative canes, many inscribed with the words, “Hit Him Again.” Southern newspapers praised the attack in editorials; when Brooks returned home after the assault, he was greeted with cheering crowds at every train stop. Following Brooks’ election, rallies displayed banners saying, “Sumner and Kansas: Let Them Bleed.” The mayor of Columbia, the capital of South Carolina, gave Brooks a gold-headed cane and a goblet inscribed with the date of the caning (May 22, 1856.)

The South reveled in Sumner’s brutal beating; people gave Brooks canes because they loved the thought of him beating Sumner again and again. And yet, even as they sadistically celebrated Sumner’s suffering, they simultaneously denied that suffering was occurring. According to Puelo:

The final indignity heaped upon Sumner was a charge repeated again and again across the South: that he was faking his injuries. Most Southerners thought Sumner’s injuries were minor and that Sumner and Northerners were exaggerating and exploiting the effects of the caning to build momentum for the Republican Party. They were right about the party’s motives but wrong about Sumner and his injuries. Indeed, the evidence is weighted heavily in the opposite direction. Throughout the summer of 1856, both Sumner himself and virtually all of the medical professionals who treated him documented his feeble condition and intense suffering. As one historian observed, if there was a plan for Sumner to feign illness, others would have been part of the conspiracy, and if there was a plot, “it was one of the best kept secrets in American history.”

Puleo says that Southerners “thought Sumner’s injuries were minor.” But again, Southerners also were celebrating the brutality of the attack. That suggests they didn’t actually believe Sumner was faking—or, more accurately, it suggests they deliberately believed whatever allowed them to feel they were in the right. They wanted to celebrate the viciousness and strength of righteous violence while simultaneously deflecting or denying fault. They embraced false stories in an orgy of bad faith and motivated reasoning. Again, it sounds pretty familiar.

Fascist Conspiracy Theories, 1856 to the Present

The South did not have social media or the internet in 1856. But they nonetheless managed to create a fascist conspiracy theory around Sumner’s beating not unlike the fascist conspiracy theories that MAGA uses today to justify their violence.

For instance, shortly after the shooting, Utah Senator Mike Lee this month posted a snarky social media meme in which he falsely insinuated that a leftist, rather than a right wing Christofascist, was behind the assassination of Democratic Minnesota state house speaker Melissa Hortman and her husband. That’s not precisely the same as Southerners saying Sumner hadn’t been hurt by his brutal beating while celebrating the beating. But it functions in a very similar way, encouraging followers to laugh and enjoy violence while disavowing their own investment. It creates a community around cruelty and bad faith. Which is a decent thumbnail description of fascism.

Perhaps you (or Will Stancil) might argue that the dynamics of fascist conspiracy theories were present in 1856, but that they weren’t as virulent or as rapid. The lies in 1856 had to travel by train and telegraph; they were disseminated by print newspapers and word of mouth. That’s a lot less efficient than our current global instant communication networks. Today, every asshole with a keyboard can make up conspiracy theories about fascist violence instantly and all at once. People who aren’t fascists can also create their own epistemic bubbles (see some Democrat’s evidenceless insistence that Harris won the 2024 election.) Surely more conspiracy theorists, and more conspiracy theories, is worse.

And yes, it might be worse in some sense. But remember that in 1856, Southern lies about Sumner were intimately connected to the massive, sweeping, widely believed lies that Black people were inferior and that slavery was just. White supremacy, Charles W. Mills has argued, is essentially “an agreement to misinterpret the world.” It’s a big conspiracy theory composed and defended by a series of smaller conspiracy theories—like the conspiracy theory that Sumner was not really injured after being savagely beaten with a cane. And these conspiracy theories led, not long after 1856, to the establishment of a vicious totalitarian state which, in the name of what you’d have to call pure evil, launched a horrific and brutal civil war.

Was the Confederacy a worse government than our current incipient totalitarianism? Was the Civil War worse than our current efforts at mass murder? You could argue back and forth if you wanted. But the core point here is that you can draw a straight line from the fascist dynamics of the Confederacy to the fascist dynamics of Trumpism. It’s the same white supremacist ideology buttressed by the same conspiracy theories in service of the same violent authoritarianism.

There are certainly differences between then and now, and those differences are important. But it’s difficult to look at the celebration of and lies around Sumner’s caning and come away with the conclusion that “Truth wasn’t endlessly malleable before.” The Confederacy didn’t have twitter; it didn’t have the internet. And yet, it nonetheless managed to be a massive white supremacist lie built upon a psychotic foundation of hate. A lie, and a hate, in which we are, I believe, still living.

Information environments are important; the internet and social media can be weaponized for radicalization; strategies for spreading fascism evolve and strategies for fighting fascism need to evolve too. I think, though, that fighting fascism needs to mean understanding fascism, and I don’t know that you can really understand the deep roots of fascism and white supremacist lies in this country if you think that the internet has corrupted our cognition and led us away from a more rational, more cognitively responsible past.

White supremacy is an evil delusion that has been widely popular among Americans (especially white Americans) ever since there was an America. It has provided the basis for reality-defying conspiracy theories that entire time. If Charles Sumner were to rise from the grave right now, I’m sure he’d have a lot of trouble adjusting. But if you managed to get him online and scrolling social media, I think he would recognize his old enemy, gripping that same ugly cane.

This is spot on. I grew up in a deeply racist rural area. My folks were active in the civil rights movement but I went to school with children of the KKK. We lived in completely different narratives-not different realities, because facts are facts.

The fascist, white nationalist cohort didn’t ever go away. They’re present in every decade of US history. You just have to pay attention. Maybe social media brought some of the virulence into the feeds of people who previously overlooked it. The US has been spoiling for this fight against democracy a long time.

I think Stancil would be right to say that the internet/social media has made it easier to propagate fascist bullshit. I'm sure it took a day or two for Sumner's caning to reach people and for the bullshit version of the white supremacists to take hold. Whereas today it would take merely minutes.

But the opposite is also true. It's never been easier to spread facts. It's never been easier to hear someone say Charles Sumner was a badass and to take 10 minutes to find out more info about him (It's a tragedy that people like Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens are less celebrated in this country than fucking Robert E. Lee) I think we're just not as good as we need to be at spreading the truth's narrative and, to quote David Lynch, fixing people's hearts.